Sharpless also didn't expect click chemistry to be used in biology.

The new tools of molecular biology at the time were not capable of studying glycans, but Caroline Bertosi tried to climb the mountain to study the elusive glycan. Bertosi developed click chemistry that can be used in vivo. This milestone achievement is also the beginning of an even bigger achievement.

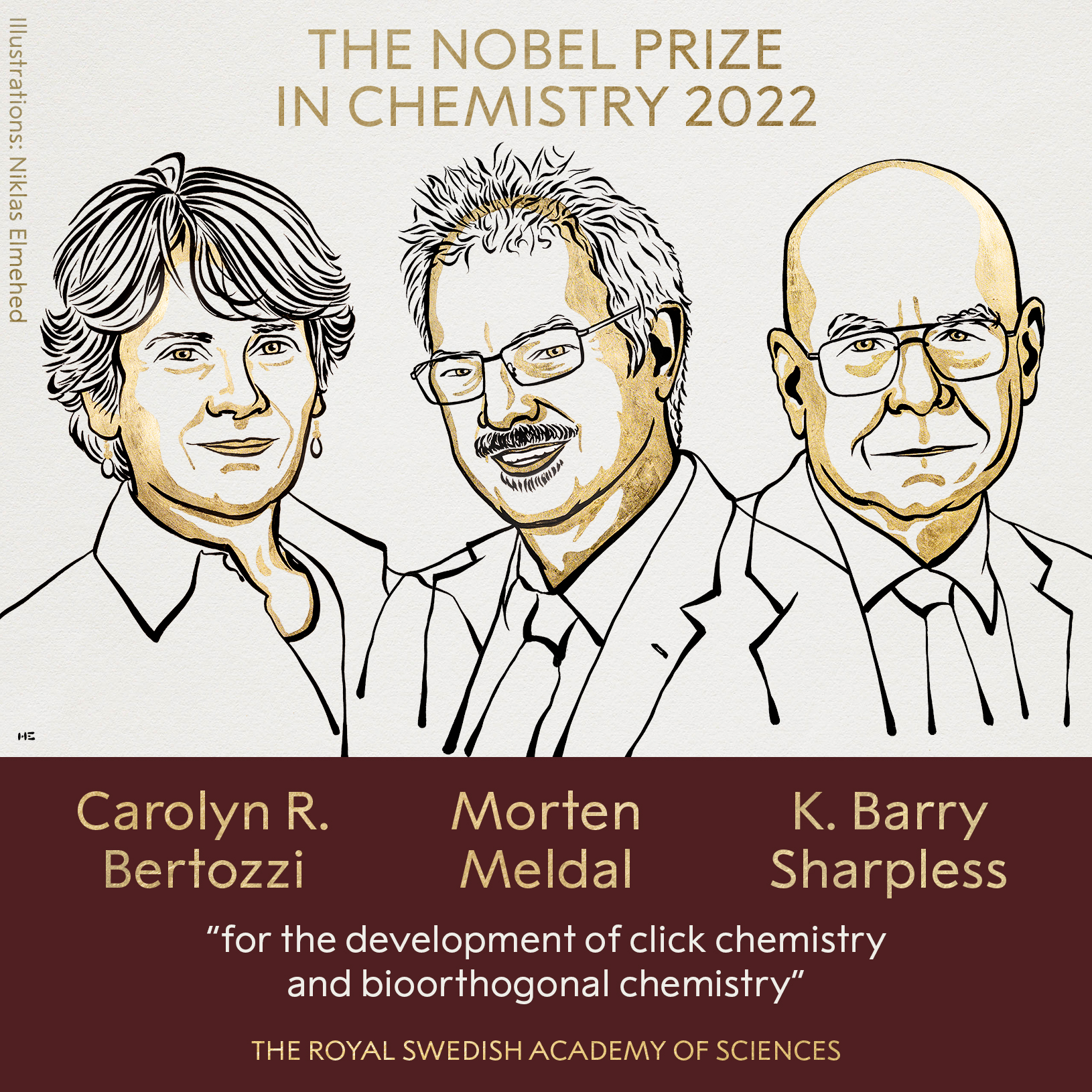

2022 Nobel Laureates in Chemistry: American chemist Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Danish chemist Morten Meldal and American chemist Carl Barry Sharpless (K. Barry Sharpless) (left to right).

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry has once again been awarded to chemistry.

On October 5, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced that the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry will be awarded to American chemist Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Danish chemist Morten Meldal and the United States Chemist K. Barry Sharpless, for their contributions to the study of click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry.

Click chemistry is a synthetic concept initially proposed by Sharpless in 1998 and gradually perfected thereafter. Its core concept is that synthetic chemistry should be guided by molecular functions, and the chemical synthesis of various molecules should be completed quickly and reliably through the simple splicing of small units.

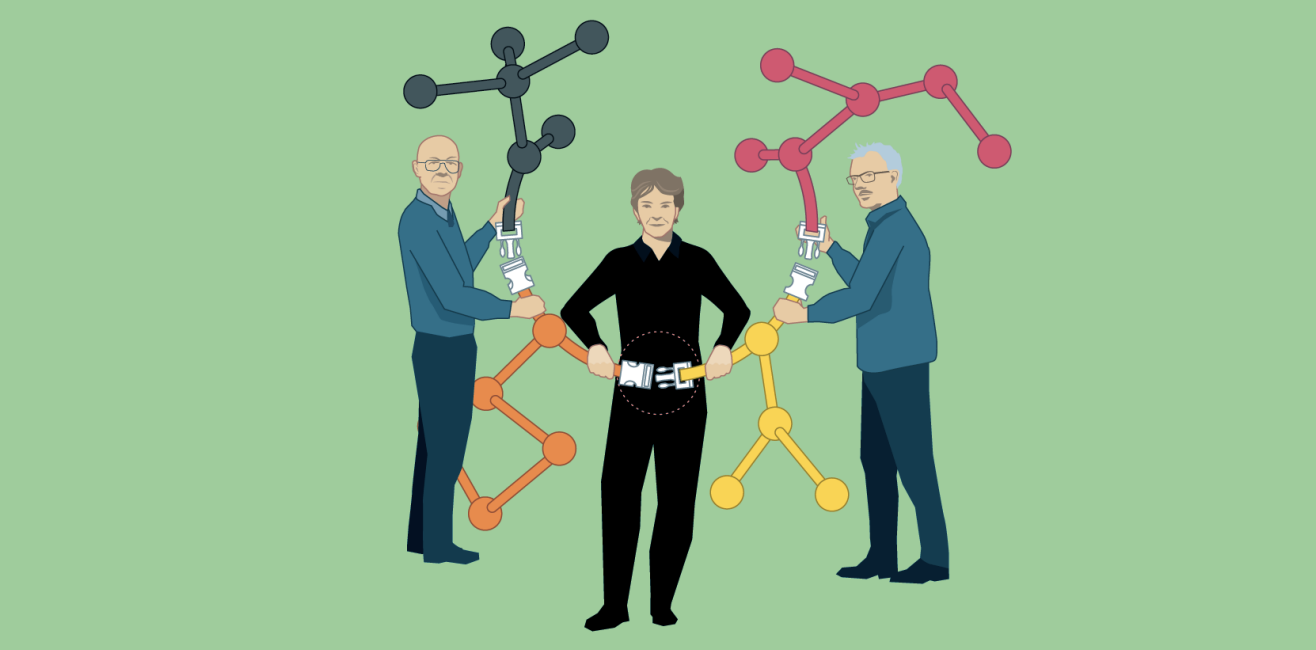

Meldal and Sharpless independently discovered the "crown jewel" of click chemistry: a copper-catalyzed azide-terminal alkyne cycloaddition. This reaction has become synonymous with click chemistry. Bertosi developed click chemistry that can be used in vivo . This bioorthogonal reaction occurs without interfering with the normal chemical reactions of cells. It is widely used to map cells. Researchers are also studying how to use these reactions. Diagnose and treat cancer.

Sharpless was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the second time. Twenty-one years ago, he shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with American scientist William Knowles and Japanese scientist Ryoji Noyori for his pioneering contributions to the field of asymmetric catalytic oxidation.

Bertosi becomes the eighth female chemistry laureate in chemistry Nobel history.

Chemistry enters the era of functionalism: Two scientists independently discover the "jewel in the crown" of click chemistry

Sharpless has said that one stumbling block for chemists is the chemical bonds between carbon atoms. Carbon atoms from different molecules often lack the chemical kinetics to bond with each other, and thus require manual activation, which often results in many unwanted side reactions and costly material loss.

So Sharpless encouraged his colleagues to start with small molecules that already had complete carbon backbones, simple molecules that could be linked together with more easily controlled nitrogen or oxygen atoms. If chemists choose simple reactions, where molecules have a strong intrinsic motivation to hold together, they can avoid many side reactions and lose less material.

He calls this method of building molecules "click chemistry."

Sharpless believes that even if click chemistry cannot provide an exact copy of a natural molecule, it may be possible to find a molecule with the same function. Guided by molecular function, it is possible to create an almost endless variety of molecules through the facile splicing of small units. He is convinced that click chemistry can produce drugs that are as applicable as those found in nature, and can be produced industrially. In a paper published in 2001, Sharpless listed several conditions that click chemistry should meet, one of which is that it occurs in the presence of oxygen and water.

The 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to Caroline Bertosi, Morton Meldal and Carl Barry Sharpless for their work in click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry.

At the other end, in a laboratory in Denmark, an unexpected substance appeared in Meldal's reaction vessel.

In the early 2000s, he had been developing methods for finding potential drugs: building huge libraries of molecules to screen to see which substances could block disease-causing processes. One day, he and his colleagues performed a routine chemical reaction to make an alkyne and an acyl halide react. As long as the chemist adds some copper ions, and perhaps a little palladium as a catalyst, the reaction usually goes well.

But Meldahl discovered that the alkyne reacted with the wrong end of the acid halide molecule, a chemical group called azide. Azides and alkynes together form a ring structure, which is a triazole.

Triazoles are ideal chemical building blocks that are commonly found in some pharmaceuticals, dyes and agricultural chemicals. The researchers had previously tried to make triazoles from alkynes and azides, but that produced unwanted by-products. Meldal realized that it was the copper ions that controlled the reaction, so in principle only one substance was formed. Even the acyl halide, which was supposed to be bound to the alkyne, was more or less unaffected in the vessel.

In June 2001, he presented his findings for the first time at a symposium in San Diego. The following year, he published in an academic journal that the reaction could be used to link many different molecules. That same year, Sharpless also published a paper on copper-catalyzed reactions between azides and alkynes, showing that the reaction was efficient and reliable in water.

The reaction between azides and alkynes is very efficient when copper ions are added. This reaction is now widely used to link molecules together in a simple way.

The azide is like a loaded spring, and the copper ions release the spring force. Sharpless suggests that chemists can use this reaction to easily connect different molecules, and the potential is huge.

It seems so now. If chemists want to link two different molecules, they can now introduce an azide in one molecule and an alkyne in the other with relative ease, and then with the help of copper ions, the molecules combine quickly and efficiently.

This simplicity also makes click chemistry popular for laboratory and industrial production, as well as for creating new materials. In drug research, click chemistry is used to produce and optimize substances that may become drugs. But Sharpless also didn't expect click chemistry to be used in biology.

Exposing Hidden Glycans: Using Bioorthogonal Reactions to Study Glycans on the Surface of Tumor Cells

In the 1990s, biochemistry and molecular biology were experiencing an explosion. Using new methods of molecular biology, researchers around the world are mapping genes and proteins in an attempt to understand how cells work. But glycans have received little attention.

This is a complex carbohydrate composed of various sugars, usually located on the surface of proteins and cells. They play an important role in many biological processes such as virus infection of cells or activation of the immune system. The new tools of molecular biology at the time couldn't study glycans, but Caroline Bertosi tried to climb the mountain to study the elusive glycan.

At a seminar, she listened to a German scientist explain his success in getting cells to produce unnatural variants of sialic acid, a molecule that makes glycans. Bertosi began to wonder if a similar approach could be used to get cells to produce a sialic acid with a chemical handle. If these cells can bind sialic acids with chemical handles to different glycans, she can use the chemical handles to map, such as labeling fluorescent molecules on the chemical handles, and the light from the glycans will reveal where the glycans are hidden in the cell. Location.

Bertosi looked in the literature for chemical handles and chemical reactions she could use, but it wasn't an easy task because the handle couldn't react with anything else in the cell, except the molecules to attach to the handle, which Must be insensitive to all molecules. To this end, Bertosi established a term to express this requirement: The reaction between the handle and the fluorescent molecule must be "bioorthogonal."

In 1997, Bertosi proved that his idea really worked. A new breakthrough came in 2000, when she found the best chemical handle: azide. She modified the Staudinger reaction in an ingenious way and used it to link a fluorescent molecule to the azide she introduced into the cell's glycan. Because azide does not affect cells, it can even be introduced into living organisms.

Bertosi's improved Staudinger reaction could map cells in a number of ways, but she's still not satisfied. Bertosi realized that the chemical handle azide he used had more uses.

During this period, the news of Meldal and Sharpless' click chemistry spread throughout the chemical community. Bertosi felt that azides could quickly bind to alkynes as long as copper ions were available, but the problem was that copper was toxic to living things.

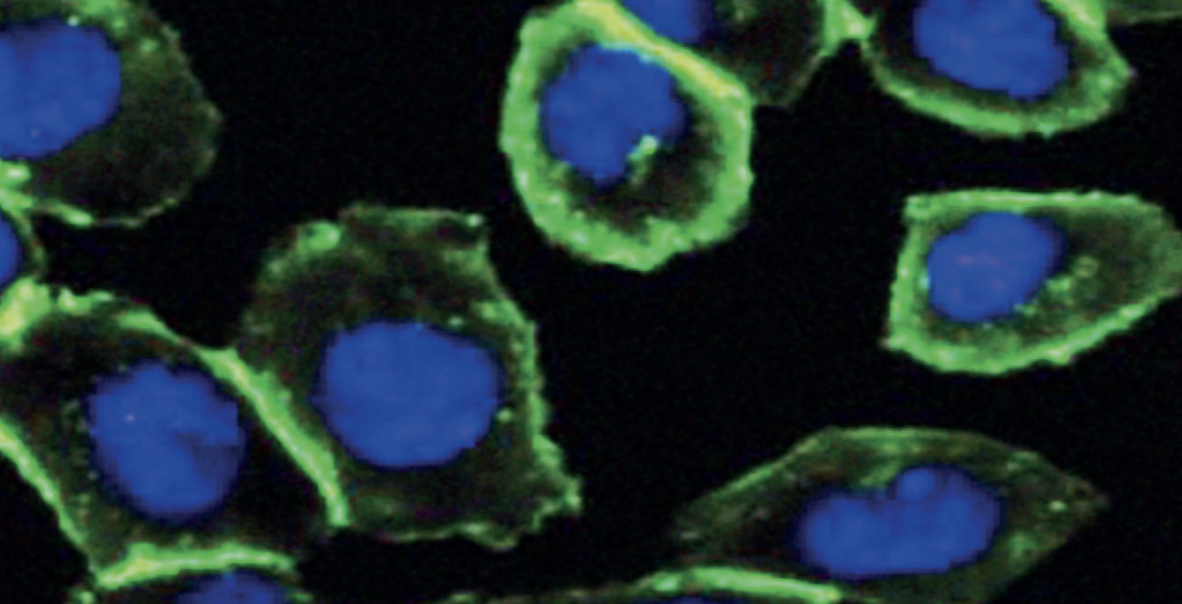

Bertosi dived into the literature again and found that studies as early as 1961 showed that if an alkynyl group was present in a cyclic chemical structure, even without the help of copper, azides and alkynes could still be almost a React in an explosive manner. So Bertosi tested the response in cells, and it worked. In 2004, she published a copper-free click reaction, known as a strain-promoted alkyne azide cycloaddition, and then demonstrated that it could be used to track glycans, allowing hidden glycans to expose themselves.

Bertosi tracking glycans via strain-promoted alkyne azide cycloaddition reactions. In the picture, the glycans glow green and the nucleus is blue.

This milestone achievement is also the beginning of an even bigger achievement. Bertosi has been refining her click response to make it work better in a cellular context. At the same time, she and many other researchers are also using these responses to explore how biomolecules interact in cells and study disease processes.

One area of interest for Bertosi is glycans on the surface of tumor cells. Her research shows that certain glycans protect tumors from damage by the body's immune system because they shut down immune cells. To block this protective mechanism, Bertosi and colleagues created a new type of biological drug. They combined a glycan-specific antibody with an enzyme that breaks down glycans on the surface of tumor cells. The drug is currently undergoing clinical trials in patients with advanced cancer.

Researchers have also begun developing click-through antibodies against a range of tumors. Once the antibody is attached to the tumor, inject a second molecule that attaches to the antibody through a click chemistry reaction, for example, a radioisotope can be added so that a PET scanner can be used to track the tumor, or the cancer cells can be given a lethal dose radiation.