· Making mistakes is a license to discover. If you don't make mistakes, you have to be a genius. Einstein once said that if your original idea is not absurd, it is hopeless.

· If you get to an island that no one has been to, the rocks will fall and the waves will be worrisome, but you might get gold nuggets all over the place. But when the others heard about the island, they would come, take all the gold nuggets, and keep digging. Until then, you'd better go somewhere else.

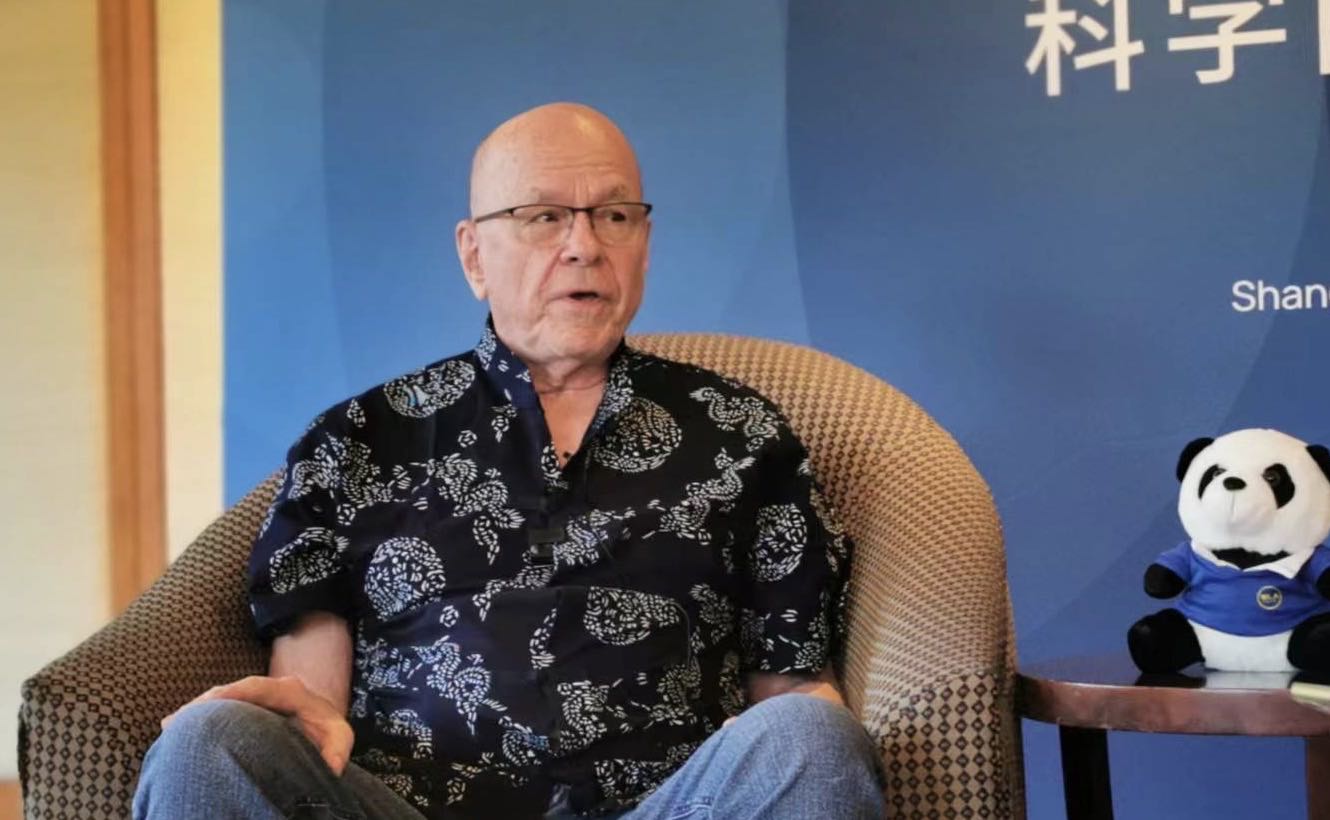

Karl Barry Sharpless, winner of the 2001 and 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, is interviewed at the World's Leading Scientists Forum, Shanghai, November 7.

Karl Barry Sharpless loved the sea and grew up dreaming of being the captain of a fishing boat, just like Uncle Dink. With a great interest in fishing, he never set out to become a scientist.

Today, the 81-year-old Sharpless is well-known in the scientific community: he is the fifth two-time winner since the Nobel Prize was established in 1901. He has won the 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. As the founder of asymmetric catalysis and click chemistry, he was elected as a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1984 and a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1985.

On November 7, Sharpless was interviewed by The Paper (www.thepaper.cn) at the 5th World Top Scientists Forum held in Shanghai. Making mistakes is a license for discovery, he said, and original innovations need to tolerate making mistakes. Discoveries cannot be planned. If you carry out scientific research with a plan, it will be difficult for your vision and judgment to escape the plan. The phenomena that are just outside the plan are interesting. Many discoveries start from discovering interesting things.

Medical student who wants to be captain goes to chemistry

Sharpless was born into a middle-class family in Philadelphia in 1941. Ever since he was a child, he has been looking for his own surprises and thrills at will. As a child, he secretly drove a motor boat up the Manasquan River in New Jersey, and drove for several miles, even through the mouth of the sea, directly to the sea. . In elementary school, he became a qualified sailor, catching eels and crabs, and at 14 he became the youngest man on a charter fishing boat at Brill Dock.

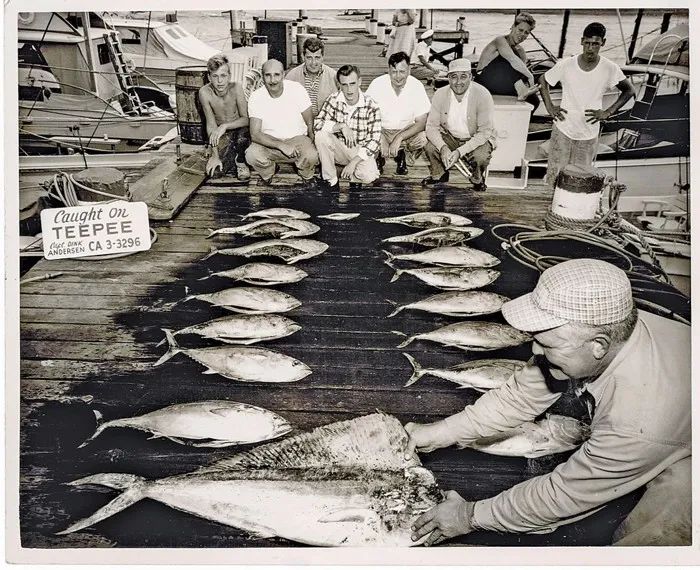

Carl Barry Sharpless (15, left) fishing with Uncle Dink on a boat.

In middle school, Sharpless felt like a not-so-bad student. His father was a surgeon, and when he went to the bookstore to buy medical books, Sharpless would follow him, picking up books on chemistry or maritime studies. His favorite book at the time was on the biosynthesis of steroids, and when he saw that the three methyl groups of lanosterol actually disappeared and turned into carbon dioxide, he thought it was "amazing".

Taking natural science courses like chemistry was easier for Sharpless, having inherited his father's unforgettable memory. In 1959, he entered Dartmouth College in the United States for university courses. A pre-med major in chemistry or biology, he prefers chemistry. He broke his leg while skiing as a freshman, and spent the winter semester on crutches to the library to study organic chemistry.

Sharpless originally planned to study medicine, but then joined the chemistry lab of assistant professor Tom Spencer at Dartmouth College. At that time, the chemical warehouse was basically open to students. He was interested in solving chemical problems, so he studied all the compounds he could find, and prepared various experiments mainly by smelling the smell. "Tom Spencer fished me out of medical school, and I loved doing research for him."

Spencer persuaded Sharpless to specialize in chemistry after seeing his talent in chemistry. When Sharpless graduated from Dartmouth College in 1963, Spencer recommended him to his mentor, Professor Eugene E. van Tamelen of Stanford University. At Stanford, Sharpless worked with Tamerlan on cholesterol biosynthesis, earning a Ph.D. in organic chemistry in 1968, followed by postdoctoral research at Stanford and Harvard.

In 1970, Sharpless joined MIT as an assistant professor and began studying chirality. A chiral molecule refers to a molecule with a certain configuration or conformation that is different from its mirror image and cannot overlap with each other. When molecules are constantly being built, two different molecules are often formed, like the right and left hands, which are mirror-image structures of each other, appearing the same but cannot overlap. The active ingredients in most drugs are chiral molecules, which often have completely different effects in the body.

Chemists usually only need one molecule in the mirror image, but it has been difficult to find efficient ways to do this, whereas asymmetric catalysis can obtain molecules of a specific chirality. In 1987, Sharpless discovered the asymmetric dihydroxylation of alkenes catalyzed by cinchonadine derivatives, which became one of the most important reactions in modern organic synthesis. Sharpless shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with American scientist William S. Knowles and Japanese scientist Ryoji Noyori for his pioneering contributions to the field of asymmetric catalytic oxidation.

Allows chemists to effortlessly achieve synthesis

Scientific research is like picking up gold nuggets on an uninhabited island. On an island that no one has ever visited, rocks will fall, waves will be worrisome, and gold nuggets may be scattered all over the place. But when other people hear about the island, they'll come to the island and take all the nuggets. "They'll keep digging, and they'll need steam shovels and dynamite to deal with it. By then, you'd better go somewhere else. ," said Sharpless.

Shortly after joining MIT, in an experiment in 1970, Sharpless lost his left eye due to the explosion of an "NMR" tube, but he was overjoyed that he could keep the vision in the other eye. His eyes did not stop him from studying on the road of chemical research. He joined Stanford University as a professor of chemistry in 1977 and returned to MIT in 1980. In 1990, he moved to Scripps Research, USA, where his research direction shifted from asymmetric catalysis to click chemistry.

Carl Barry Sharpless and his student Dong Jiajia, Dean of the Institute of Translational Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Click chemistry is a synthetic concept initially proposed by Sharpless in 1998 and further perfected in 2001. Just like building Lego blocks, it can quickly and reliably complete various molecules through the splicing of small units. The most representative reaction is the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction, which has been widely used in the synthesis of organic and polymer semiconductor materials, supramolecular aggregates and molecular self-assembly, biomolecular labeling, antibody modification, drug development and a series of important research and production areas.

In 2002, Sharpless published a paper on copper-catalyzed reactions between azides and alkynes, showing that the reaction was efficient and reliable in water. The azide is like a loaded spring, and the copper ions release the spring force. He suggested that chemists can use this reaction to easily connect different molecules, and the potential is huge. If a chemist wants to connect two different molecules, they can introduce an azide in one molecule, an alkyne in the other, and then, with the help of copper ions, the molecules combine quickly and efficiently, and chemistry enters the era of functionalism .

"Click sounds cute, and click chemistry is hard not to be seen as a joke." But Sharpless sees it as a way for chemists to make something useful without much effort. "It's a discovery Good way of things, it's not a joke."

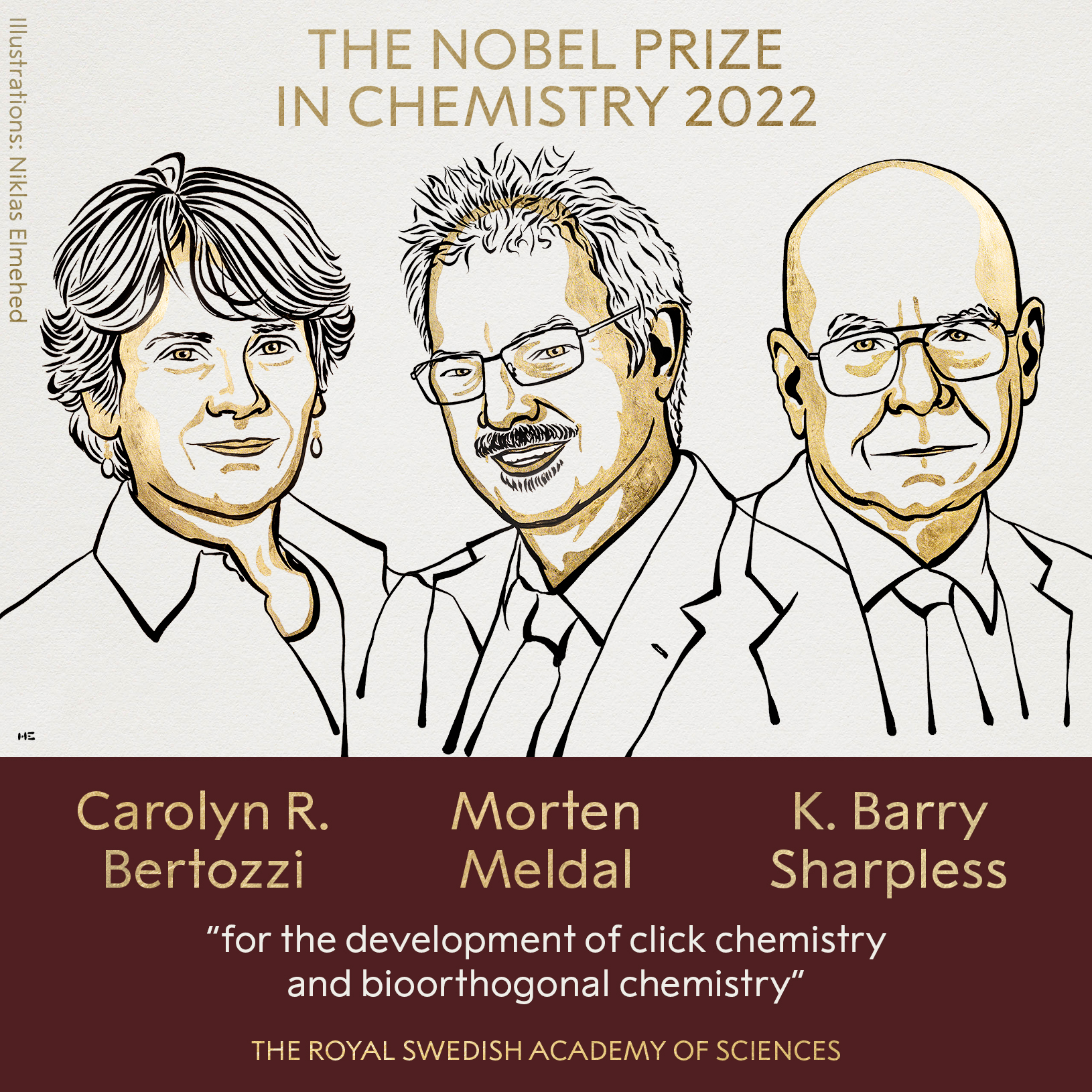

This really isn't a joke. Twenty years later, for his contributions in click chemistry and bioorthogonal chemistry, Sharpless joined forces with American chemist Carolyn R. Bertozzi and Danish chemist Morten Meldahl. Meldal) won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Sharpless also became the second scientist to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The 2022 Nobel Laureates in Chemistry: American chemist Caroline Bertosi, Danish chemist Morton Meldahl and American chemist Carl Barry Sharpless (left to right).

For Sharpless, the engine that drives all his thoughts and actions is passion, not planning, because discoveries cannot be planned. "A lot of discoveries start with discovering interesting things." fish, but have been "fishing" for strange things, "small things like chemical molecules, people can't see them, so the surprises there are limitless", what people can find in them.

The following is a transcript of the conversation between The Paper and Carl Barry Sharpless. Sharpless was accompanied by Dong Jiajia, a professor at the Institute of Translational Medicine at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and Sharpless mentioned this proud student many times in the interview.

The Paper: Professor Tom Spencer once persuaded you to specialize in chemistry. What is your style when you work with your own students?

Sharpless: That's an interesting topic. I used to be a medical student and Tom Spencer fished me out of medical school and I loved doing research for him. Interestingly, his character is very inspiring to me. He's a good teacher, but a bit sarcastic. So I always want to impress him. One summer night I was working in a lab doing distillation. Towards the end, the container became very hot and there was smoke coming out. I overturned the oil bath container while measuring the pressure, the oil spilled on my blue jeans, it hurt so much, I quickly took off my jeans. He came in when he heard the sound, looked at it, realized there was nothing he could do, said "uh" and left and went back to his office, hahaha.

A friend who graduated with me didn't do well in Tom Spencer's lab at the time, so he went to medical school. He was gone when I came to Spencer's lab, but together we gave Spencer a large fire-resistant helmet because one day Spencer caught fire while he was showing us how to do hydrogenation. He had methanol and a palladium catalyst, both exposed to oxygen, and it caught fire.

All in all, he is a very good teacher.

Surging Technology: How did you feel when you won the Nobel Prize for the second time? What were you doing when you learned of the award?

Sharpless: I'm sleeping. My wife was awake and she looked it up online and there were pictures of Caroline Bertosi and Morton Meldal and me. She showed me the picture with her computer, I saw it, and went back to sleep. I swear to God, I did fall asleep again. Decided to keep sleeping because I've had it once before.

Surging Technology: From your experience, when exploring a new scientific research field, even if no one believes you can succeed at first, or that what you do is useful, how do you persevere in this situation?

Sharpless: That's a good question, too. When I wonder if the chemistry is working, or if it's really special or better, if I feel that way and the reaction doesn't work, I tell myself to try again. In 1975, one or two students couldn't do chemistry and gave up, and I tried again two years later. I tried again because the thought came back to my mind. If I remember something a few times, it keeps coming back to me, it's a message from someone, it's my subconscious mind, and it's very important, so I keep trying. We have been working on a subject for 40 years, and the students have not been able to do it, which is very strange. The Germans did it back in the 1920s, but why didn't we make it, and the German students did. But Dong Jia's family did not give up and made it. [Note: Sharpless's group has been hoping to repeat the experiments of German chemist Wilhelm Steinkopf (on the synthetic chemistry of sulfonyl fluorides) from 1927 to 1930, but it has been unsuccessful for many years . His postdoctoral fellow Dong Jiajia did not give up, and he finally succeeded after receiving a bottle of sulfuryl fluoride from Dow. His discovery opened the hexavalent sulfur-fluorine exchange reaction (SuFEx), the second near-perfect click chemistry reaction discovered in the Sharpless lab. 】

Click sounds cute, click chemistry is hard not to be seen as a joke, because they just see it as a joke, but Dong Jia's and the rest of us see it as something that chemists can make without much effort A way of things, it's a good way to discover things, it's not a joke.

Surging Technology: You dream of being a captain of a fishing boat, and now you have won the Nobel Prize twice; you originally planned to study medicine, but ended up working hard in the field of chemistry. What is your research drive, interest, excitement or fear? Will you fish again?

Sharpless: I'm not fishing anymore, I'm "fishing" for weird stuff. With things as small as chemical molecules, people can't see them, so the surprises there are limitless. We will never see in human existence, so something can be found in it.

If you're Columbus, Captain Cook or Magellan, you can go out to sea and conquer islands no one has ever been to. That's what I think is the most exciting thing about being a human, and maybe the adventurous can only imagine that. If you get to an island that no one has been to, the rocks will fall and the waves will be worrisome, but you might end up with gold nuggets all over the place that you can just pick up. But when other people hear about the island, they'll come, they'll take all the gold nuggets, they'll keep digging, and they'll need steam shovels and dynamite to deal with it. Until then, you'd better go somewhere else.

There is a plan to be organized. You can plan, but you can't find it. A lot of discoveries start with finding something interesting, a chemical reaction that produces something interesting, and you find it's really interesting.

Everyone wants to do well and impress themselves, friends and professors. But one of my professors taught me one thing in the 1960s and 1970s, he told me to never do what you are capable of, this is not a general advice to scientists, engineers, engineers have to create something . He was an unusual man who left the chemical world early to develop real estate for the Japanese in Hawaii and became a millionaire.

Surging Technology: How to achieve original innovation? What kind of research environment is needed to support original innovation?

Sharpless: I think we rely a lot on mistakes in our lives, everyone makes mistakes, chefs make mistakes, and then discover something wonderful. Making mistakes is a license for discovery, but people are often embarrassed by making mistakes.

If you don't make mistakes, you have to be a genius. So you should expect students to make mistakes, you just have to encourage them to do things their own way, and then you can point out mistakes, but it's just a necessary upgrade to the baseline of making mistakes.

Some physicists have crazy ideas. Einstein, one of the most creative physicists, once said that if your original idea is not absurd, it is hopeless. It's not worth mentioning if it's not absurd, it's okay, but not the ultimate type, not the Einstein type.

The Paper: What are your suggestions for the development of young scientists? How to stay curious?

Sharpless: Some people are naturally curious about science, they look at things they don’t understand, and a lot of things in nature help spark curiosity, because some things seem inanimate, but they move and can really scare kids. This is a very important basic excitement.

An American female writer said that the antidote to boredom is curiosity, but curiosity has no cure. You see, you are cured of this disease, but you have another disease. This is also a kind of "I am too difficult". You have to realize that in a way this is a kind of torture for creative work.

I tell you a story. I knew a student from Jia Dong's family, we worked together in those years, the student was amazing, I could see he was thinking hard and putting his heart and soul into what he was doing. Now he has grown into a very good creative chemist. Dong Jia's family encourages them, but does not control them. I think one can come up with incredible things at 30 years old by following one's interests.