According to statistics, more than 100 million people in China suffer from various types of liver diseases, among which 50%-70% of patients with cirrhosis will further develop hepatic encephalopathy.

On January 8, Nature Medicine, a top international medical journal, published a paper online, revealing for the first time the key role of phenylethylamine produced by intestinal bacteria in the occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy.

Professor He Xiaolong of Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University, one of the co-first authors of the paper, told The Paper that hepatic encephalopathy is a neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with liver failure or severe liver disease (such as cirrhosis). It is caused by the liver's inability to effectively eliminate toxins from the blood, which accumulate in the brain.

Hepatic encephalopathy usually manifests as memory loss, confusion, and even loss of consciousness, and can be life-threatening in severe cases.

Experiments on mice have shown that transplanting fecal microbes from patients with hepatic encephalopathy into germ-free mice can replicate the neurological symptoms associated with hepatic encephalopathy, and treatment targeting phenylethylamine (PEA) can reverse the aforementioned neurological symptoms.

The researchers believe that the newly published research results have expanded people's understanding of the "gut-liver-brain axis" and identified a promising target for predicting and treating hepatic encephalopathy.

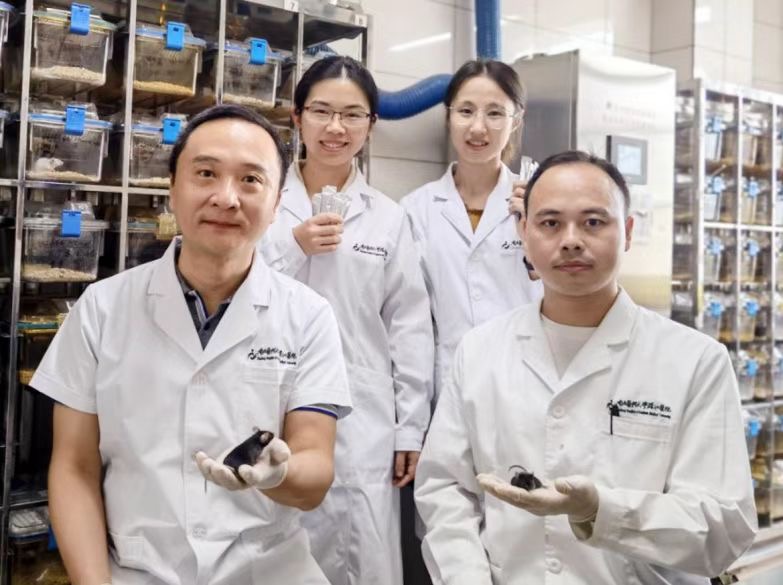

Professor Zhou Hongwei of Southern Medical University Shenzhen Hospital (front row, left), and Professor He Xiaolong of Southern Medical University Zhujiang Hospital (front row, right).

In the past, it was generally believed that ammonia produced by intestinal bacteria was the culprit, but clinical studies have found that ammonia cannot fully explain the occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy.

In a newly published study, researchers systematically evaluated metabolites produced by intestinal flora and found that phenylethylamine is an important driving factor for the occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy.

Phenylethylamine is produced by Ruminococcus active, a common intestinal bacterium, and circulates through the blood into the brain. The level of the phenylalanine decarboxylase (PDC) gene, which comes primarily from Ruminococcus active, increased about 10-fold in patients with cirrhosis and even more in patients with hepatic encephalopathy.

The accumulation of phenylethylamine is mainly due to the decreased activity of monoamine oxidase B in the liver and serum caused by cirrhosis.

The study found that when patients with cirrhosis underwent intrahepatic portal vein shunt (TIPS) treatment, those with higher preoperative phenylethylamine levels had almost 7 times the risk of developing hepatic encephalopathy compared with other patients.

This newly published study proposes a new hypothesis: testing blood levels of phenylethylamine can help doctors predict a patient's likelihood of developing hepatic encephalopathy, and even provide early diagnosis and intervention before the patient's condition worsens.

In addition, the research team is further exploring the effectiveness of drugs that inhibit the production of phenylethylamine in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy to help improve patients' quality of life.

He Xiaolong, Hu Mengyao, Xu Yi, Xia Fangbo from the Department of Laboratory Medicine, Zhujiang Hospital, Southern Medical University, and Tan Yang from the Qingdao Institute of Energy and Process Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences are the co-first authors of this article.

Professor Zhou Hongwei from Southern Medical University Shenzhen Hospital, Professor Gao Jie from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Professor Qi Xiaolong from Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University, and Professor Chen Jinjun from the Liver Disease Center of Southern Hospital are the co-corresponding authors of the aforementioned newly published paper.

Attached paper link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03405-9