Speaking of PubMed, many small partners are very familiar with it. This should be the most commonly used biomedical-related SCI literature retrieval database in China.

Recently, a report in Nature claimed that at least 1% of the papers may have come from the paper factory after being detected by a software tool called Papermill Alarm, such a widely acclaimed literature search ensemble.

What is the concept of 1%? According to PubMed's official website, the database contains more than 34 million biomedical literature, and "at least 1%" means that more than 340,000 papers may be suspected of falsification.

"This figure is too high and worrying." Smut Clyde, an academic anti-counterfeiter, laments. "These rubbish papers do get cited, and people use them to support research projects that they have no way out."

Another academic anti-counterfeiter, Elisabeth Bik, believes that the actual number of articles from the paper factory on PubMed may be higher. "These papers will damage the reputation of science and our trust in research papers."

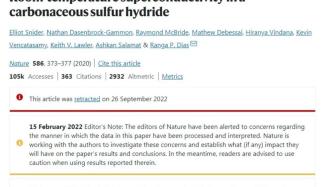

In recent years, the number of papers retracted by journals has been increasing, and behind these retraction data, paper factories have played an important role. The increasingly large-scale and industrialized methods of academic fraud are invading the scientific community, and it is imminent to crack down on the paper factory.

The protracted battle with the "dissertation factory"

When there is academic fraud, there will be counterfeiters. A protracted battle is waged between them and the paper mill.

Clyde has been tracking evidence of academic misconduct for years. Along with other academic anti-counterfeiters, he flagged hundreds of articles that may have been produced by paper factories. These paper factories churned out fake academic papers and sold them to researchers in need.

Publishers have withdrawn many suspicious papers and have taken steps to prevent journals from accepting submissions produced by paper factories. But the problem still exists.

Clyde is just one of many researchers working on this anti-counterfeiting effort. They usually take the academic crackdown as a pastime outside of their main work, so they like to use pseudonyms to crack down on fakes. Others, like Bik and molecular oncologist Jennifer Byrne, opted for real names to crack down on fakes.

In April, Clyde’s email address appeared on a Research Square server in a preprint article describing a paper factory. The author of the article is David Bimler, a retired psychologist who worked at Massey University in New Zealand.

After confirming that Clyde and Bimler were the same person, Nature interviewed the person to discuss issues such as the paper factory.

The article, published in a preprint, caused an uproar. In the article, Bimler pointed out that from 2015 to 2022, more than 800 papers in the field of dubious chemistry came out of the same paper factory, and these papers were characterized by repeated images, strange wording, suspicious email addresses, meaningless citations, etc. And they all claim that metal-organic frameworks have effects such as killing cancer cells or inhibiting inflammation.

"I'm amazed that so many papers are on the intersection of advanced chemistry and medical applications." Bimler says that metal-organic frameworks do have some fantastic physical properties, which is why people are so enthusiastic about them. But the idea that they might have medical properties is extremely far-fetched, and these journals receive hundreds of papers on them.

In recent years, large-scale academic fraud is affecting publishers.

For example, in early 2021, the Royal Society of Chemistry Advance journal retracted 69 papers suspected of academic fraud. None of these papers had a common author or institution, but the icons and titles in the texts were strikingly similar. The journal was also the victim of a "massive academic fraud" scam, the official statement said.

The journal's executive editor, Laura Fisher, is aware that some paper factories are churning out pseudoscientific articles.

An analysis by Nature found that journals have retracted at least 370 papers related to the paper factory since January 2020, with many more expected to be retracted in the future.

Much of this literature clean-up has occurred because academic anti-counterfeiters have publicly flagged suspicious papers they believe come from paper mills.

The editors take this issue very seriously. So much so that in September 2020, London's Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) held a forum dedicated to the topic of "systematic manipulation of the publishing process by dissertation factories".

Bik is the guest speaker of the forum. She has worked at Stanford University School of Medicine for 15 years, and later became a professional academic anti-counterfeiter, specializing in investigating the duplication of images in various papers and possible academic misconduct. There are thousands more such papers in the literature, Bik believes. "It's sighing that so many papers are fake."

According to Nature's statistics, by March 2021, there will be more than 1,300 papers listed as suspicious papers by these academic anti-counterfeiters. About 26% of the articles have been retracted or tagged as closely watched, and many are still under investigation.

Medicine is the hardest hit area for essay writing

In most retracted papers, the medical field was the hardest hit.

According to Nature statistics, since January 2020, more than 370 retracted papers claimed by academic anti-counterfeiters came from paper factories, and their authors were all from hospitals.

In July 2021, the Journal of Cellular Biochemistry withdrew 129 papers from China, and even published a special supplement, Supplement Retraction Issue, a collection of retracted papers. It's especially shocking that all the papers here are from the hospital group.

The editor-in-chief of the journal, Christian Behl, a professor at the University of Mainz in Germany, even wrote an editorial to explain the supplement and condemn the paper factory. “Recently, paper factories have become a hot topic of discussion, and publishers, editors, reviewers, etc. are all very concerned about this topic. Paper factories have posed a huge threat to research integrity.”

Physicians are a special target market because they usually need to publish research papers to get promoted, but they are too busy in the hospital to really have much time for scientific research, said Xiaotian Chen, a librarian at Bradley University in the United States. and write articles.

This is why the medical field has become the hardest hit by fake papers.

The prevalence of questionable papers has led some journal editors to doubt papers submitted by Chinese medical researchers. In February 2021, an editorial in Molecular Therapy said, "The growing number of such 'problem papers' is seriously undermining the credibility of Chinese academics doing research and increasingly casting doubt on scientific normativeness in the region. ."

Catriona Fennell, head of publishing services at Elsevier, the world's largest scientific publisher, pointed out that the problem of organized fraud in the publishing industry is not new, and it is not limited to China.

"We have also found evidence of industrialized fraud in several other countries, including Iran and Russia. This is already a global problem," she told Nature.

The fake "nemesis" is coming

Publishers have been battling academic fraud. Many publishers also use software and other methods to help detect fraud and spot fake papers. For example, with some manuscript processing systems it is possible to detect and flag many submissions from the same computer.

Adam Day, the developer of Papermill Alarm and director of Clear Skies, an academic data service in London, UK, said, "Its method of analyzing text is state-of-the-art."

Papermill Alarm can massively analyze the titles and abstracts of scientific papers, and detect similar text content with fake articles, which is simply a fake "nemesis".

The tool uses a deep learning algorithm to compare the language used in the titles and abstracts of submitted articles with articles known to come from the paper factory. This comparison is based on a list of Paper Factory articles compiled by people like Bik and Bimler (also known by the pseudonym Smut Clyde) who study scientific integrity. The tool uses a traffic light pattern, assigning red flags to papers with many similarities to known Paper Factory articles, orange flags to those with individual similarities, and green flags to those with no similarities.

"It's not a fishing rod, it's like a fishing net," Day said of the text analysis tool.

Its excellent features have caught the attention of some publishers. Six publishers have expressed interest in using Papermill Alarm to screen submissions, including SAGE, a well-known independent academic publishing company, where Day works as a data scientist.

The easy "catch all" of potentially fake papers is becoming a reality. Such a paper detection tool does benefit journal editors, but it should be noted that the software does not clearly indicate whether a paper is fake, but can filter out questionable articles that need further investigation.

Reference link:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-02997-x

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-02099-8

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00733-5

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01363-z

(Original title "Nature Post: Over 340,000 Papers in World-renowned Databases Suspected of Falsification")