The record-breaking temperatures came faster and more violently than researchers expected, raising concerns about what the future holds.

Unprecedented heatwaves have swept many parts of the world over the past few weeks, from London to Shanghai. Tokyo recorded nine consecutive days above 35ºC in June, the worst local heatwave since records began in the 1870s. In mid-July, the UK saw its first high temperature above 40ºC since temperature measurements began. Meanwhile, wildfires caused by heatwaves have spread in France, Spain, Greece, Germany and more. Widespread heat waves in China have also followed, including one that hit more than 400 cities last week.

Researchers are working non-stop to study this year's heatwave to better understand how future extreme heat will affect human society.

“The scientific community has been thinking about the possibility of these events happening before,” said Eunice Lo, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol who studies British heatwaves, but “to see these events in action is incredible.”

deadly heat wave

Extreme heat is a deadly consequence of global warming. It kills people directly, like those outdoor workers. It can also paralyze power grids, cutting off life-saving power to air conditioners or fans. A heatwave in Europe in 2003 was estimated to have killed more than 70,000 people. Not only that, but heat waves can exacerbate disasters such as wildfires and cause significant psychological trauma to humans.

While heatwaves have intensified over the past few years, research into the most extreme heatwaves has come a long way since a heatwave event hit North America's Pacific Northwest in June 2021.

That heatwave, still at record highs, essentially reshaped the field of research on extreme heat, said University of Bristol climate scientist Vikki Thompson. In a study published in May, she and colleagues pointed out [2] that, since 1960, only five heatwaves have been more severe globally than that one, if one looks at the deviation from the climate of the previous 10 years. Just looking at temperature data for the entire Pacific Northwest in the years leading up to that heatwave, she said, the unprecedented heatwave was almost "totally unjustifiable." But it did happen, mainly due to a constant influx of hot air from a high-pressure atmospheric system, combined with hotter-than-usual soil temperatures in much of the region.

beyond expectation

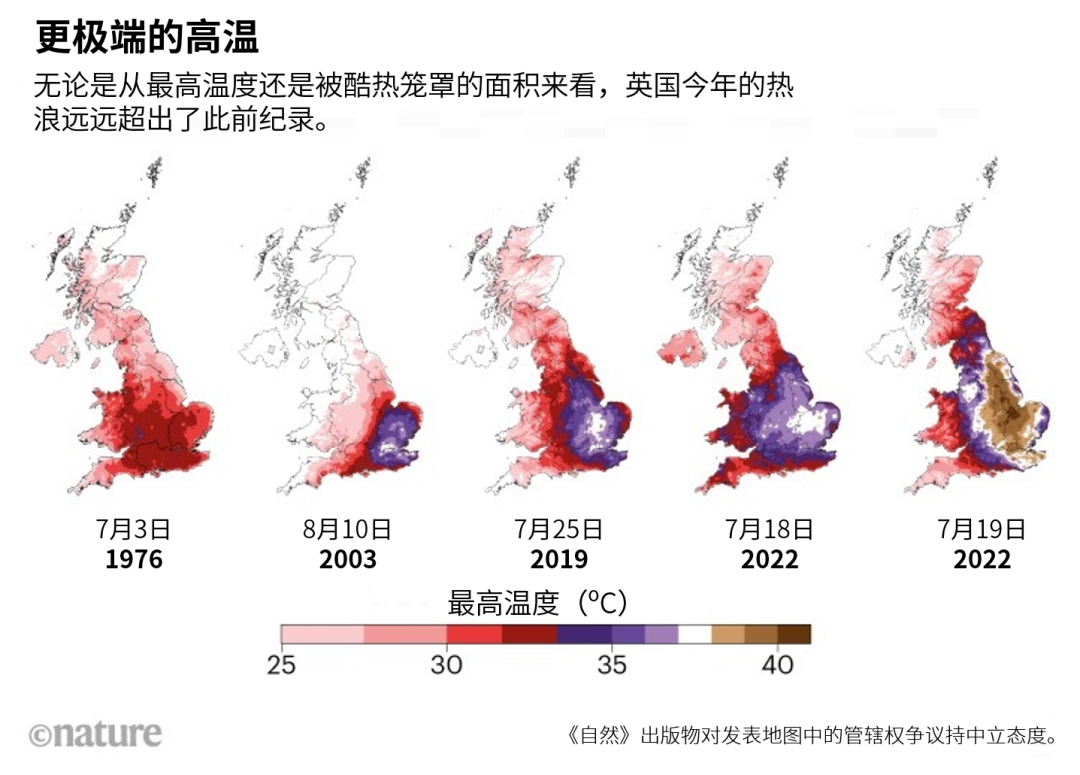

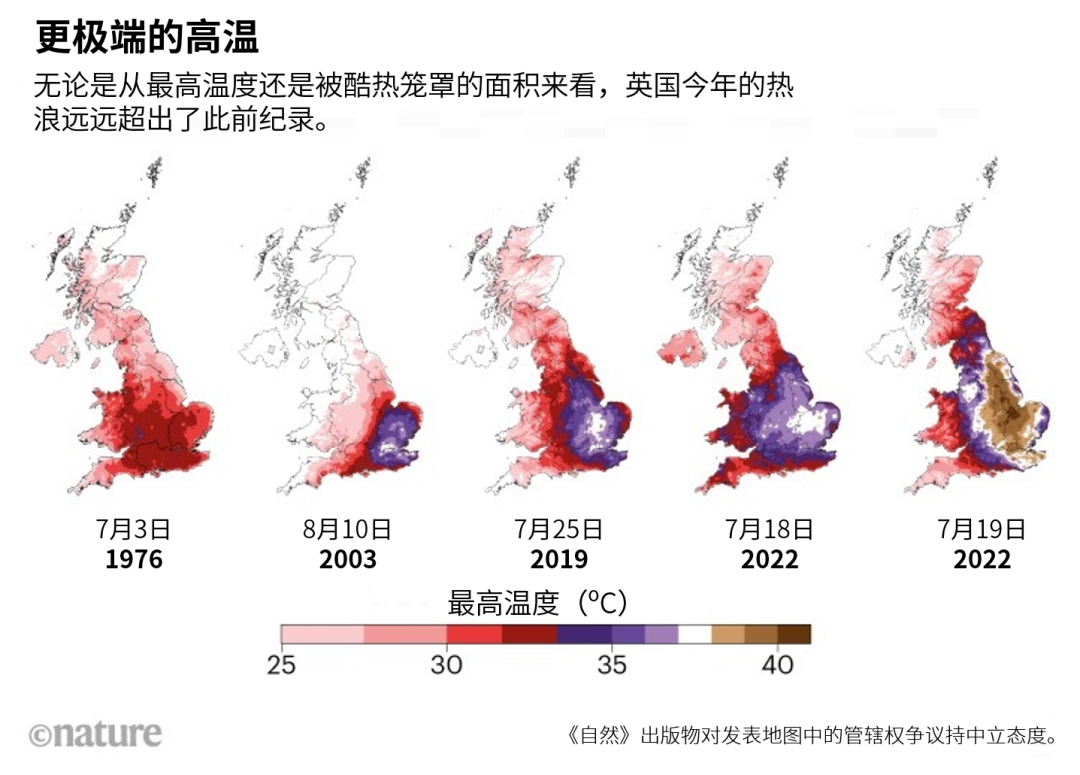

Although the UK heatwave in July was not as severe, it will still go down in history as it made the country aware of the dangers of extreme heat. On July 18 and 19, heat records were broken in many places in the UK, by a full 3 to 4ºC above the previous record (see 'More extreme heat'). 46 weather stations set a new high temperature record of 38.7ºC set just three years ago. It is estimated that hundreds of people may have died as a result.

The reason why the temperature exceeds the threshold faster than expected may be because climate models cannot capture all the factors that can affect the heat wave, so it is difficult to accurately predict the extreme high temperature in the future [4]. Changes in factors such as land use and irrigation can affect heatwaves in ways that models cannot fully capture, meaning models sometimes misjudge the true impact of climate change.

An analysis published on July 28 by an international team of researchers from World Weather Attribution found that human-caused climate change has increased the incidence of heatwaves in the UK this year by at least 10 times [5]. The study also found that without climate change, heatwaves should have been 2–4ºC cooler.

"More evidence that our models may be missing something," said Peter Stott, a climate scientist at the Met Office, co-author of the 2020 UK study[3]. question."

Erich Fischer, a climate scientist at ETH Zurich, said that, like the 2021 heatwave affecting the Pacific Northwest, the 2022 British heatwave may also allow researchers to find out more quickly what is causing the heatwave than our own. Expected to be more extreme. In a modeling study[6] published last year, Fischer and colleagues projected that the next few decades would see record-breaking climate extremes. "That's exactly what we're seeing now," he said.

Fischer said that studying the magnitude of record-breaking extremes, not just whether records were broken, could help local governments deal with extreme events that may be encountered in the near future.

Dynamic changes

With the exception of the UK, most of Europe has seen several heat waves this year. In fact, Europe has broken heat records more than once in the past five years, says Kai Kornhuber, a climate scientist at Columbia University in New York. His team found that Western Europe is very prone to heat waves [1]. Over the past 40 years, Western Europe has experienced extreme heat three to four times as often as other mid-latitude regions in the Northern Hemisphere.

This may be because the eastward-moving atmospheric jet stream in the North Atlantic often splits in two as it approaches Europe. In this case, the two currents would move the storm away from Europe, allowing the heatwave to form and continue. While it's unclear whether climate change will lead to more of these "twin jets," these types of climate patterns contributed to the July heatwave in Western Europe and are responsible for many recent heat events there.

We may find that similar patterns of atmospheric dynamics are important for revealing what makes high temperature events more extreme than expected, Kornhuber said.

heat wave concurrent

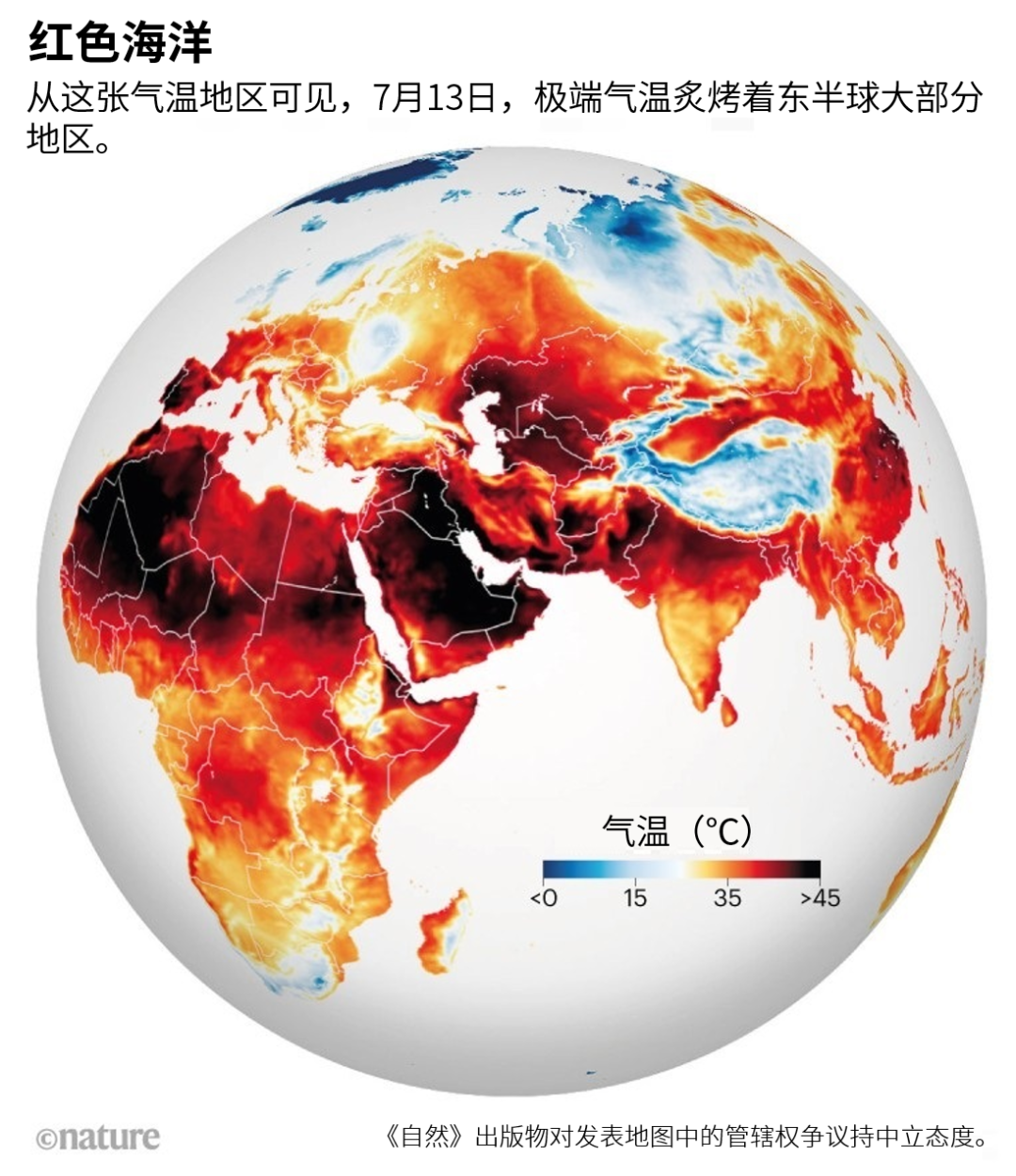

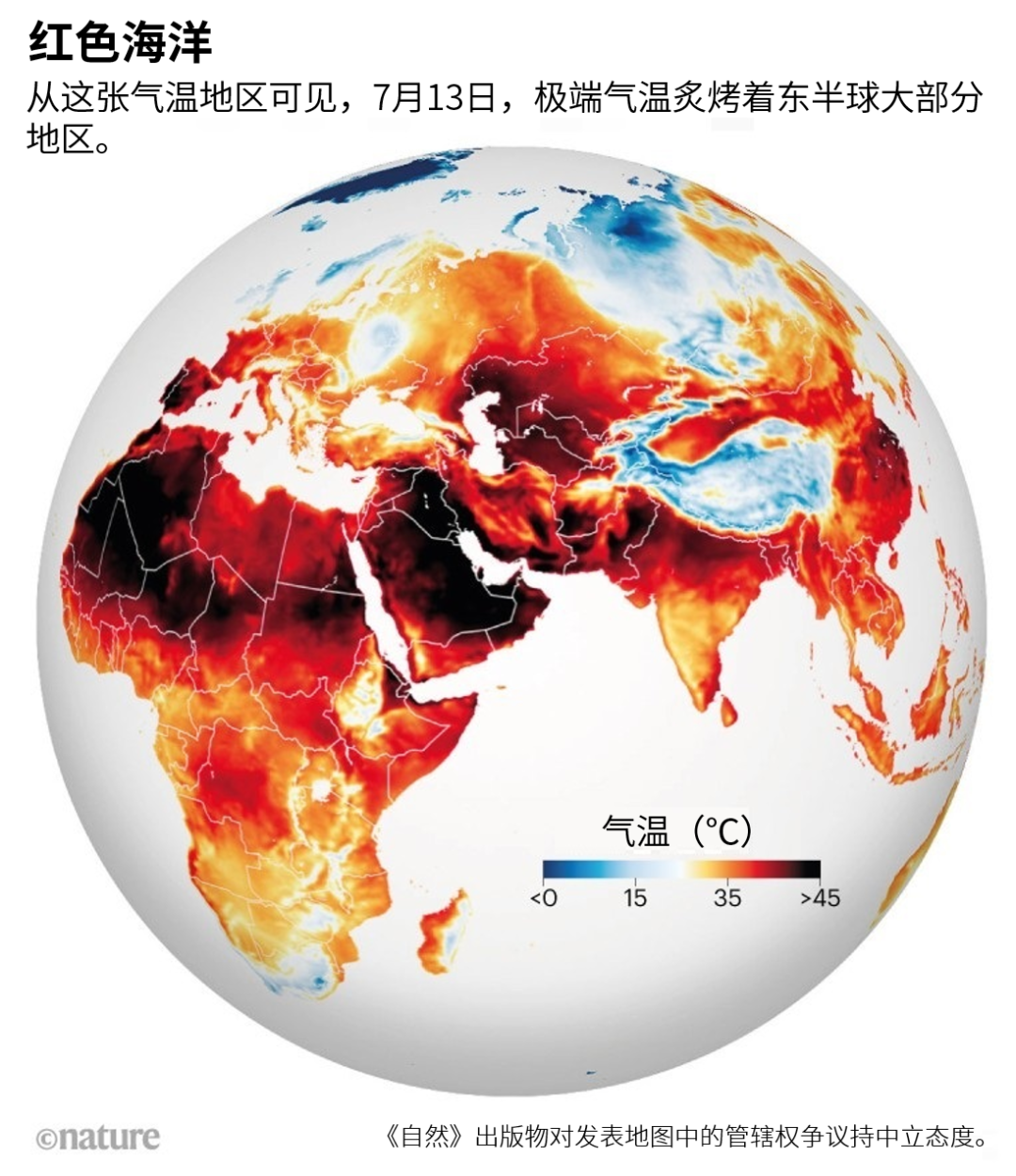

Another distinctive feature of the past few months has been the near simultaneous occurrence of extreme heat in many parts of the world (see "Red Ocean"). At the end of July, China and western North America entered a warmer-than-usual high temperature pattern at about the same time as Europe. A study published in February found that between 1979 and 2019, the frequency of such heatwave concurrent events increased fivefold.

This year, the heatwave has also arrived earlier in certain regions, such as India and Pakistan, which have been experiencing unbearably high temperatures from March to May this year. Parts of India surpassed 44ºC at the end of March, well ahead of the hottest period in previous years. At least 90 people died as a result. The World Climate Attribution found that climate change increased the probability of this heatwave by 30 times [9].

As global temperatures continue to rise, climate scientists have been stressing the importance of cutting carbon emissions and accelerating human adaptation to extreme temperatures. Stott said the heatwave in the UK had woken up a lot of people to see how vulnerable the country was to extreme heat. Stott, who has worked in climate forecasting for decades, was most surprised to see extreme heat ignite wildfires in central London. "That scene was really shocking."

references:

1. Rousi, E., Kornhuber, K., Beobide-Arsuaga, G., Luo, F. & Coumou, D. Nature Commun. 13, 3851 (2022).

2. Thompson, V. et al. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm6860 (2022).

3. Christidis, N., McCarthy, M. & Stott, PA Nature Commun. 11, 3093 (2020).

4. Van Oldenborgh, GJ et al. Earth's Future 10, e2021EF002271 (2022).

5. Zachariah, M. et al. Without human-caused climate change temperatures of 40 °C in the UK would have been extremely unlikely. (World Weather Attribution, 2022).

6. Fischer, EM, Sippel, S. & Knutti, R. Nature Clim. Change 11, 689–695 (2021).

7. Rogers, CDW, Kornhuber, K., Perkins-Kirkpatrick, SE, Loikith, PC & Singh, DJ Clim. 35, 1063–1078 (2022).

8. Kornhuber, K. et al. Nature Clim. Change 10, 48–53 (2020).

9. Zachariah, M. et al. Climate Change made devastating early heat in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely. (World Weather Attribution, 2022).

The original text was published on the news feature section of Nature on August 4, 2022 under the title Extreme heatwaves: surprising lessons from the record warmth. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-02114-y

(Original title "Why is it so hot this summer? | "Nature" long article"; The Paper is reprinted with permission)

Unprecedented heatwaves have swept many parts of the world over the past few weeks, from London to Shanghai. Tokyo recorded nine consecutive days above 35ºC in June, the worst local heatwave since records began in the 1870s. In mid-July, the UK saw its first high temperature above 40ºC since temperature measurements began. Meanwhile, wildfires caused by heatwaves have spread in France, Spain, Greece, Germany and more. Widespread heat waves in China have also followed, including one that hit more than 400 cities last week.

Firefighters in southwestern France fight fires ignited by an extreme heatwave on July 17. Credit: Thibaud Moritz/AFP/Getty

Climate scientists have previously warned that as the world warms, heatwaves will become more frequent and temperatures will be higher. But according to a study[1] published last month, that future is coming sooner than researchers feared, especially in Western Europe, a heatwave "hot zone". These record-breaking heatwaves are not only getting higher and higher, but even completely exceeding climate model predictions.Researchers are working non-stop to study this year's heatwave to better understand how future extreme heat will affect human society.

“The scientific community has been thinking about the possibility of these events happening before,” said Eunice Lo, a climate scientist at the University of Bristol who studies British heatwaves, but “to see these events in action is incredible.”

deadly heat wave

Extreme heat is a deadly consequence of global warming. It kills people directly, like those outdoor workers. It can also paralyze power grids, cutting off life-saving power to air conditioners or fans. A heatwave in Europe in 2003 was estimated to have killed more than 70,000 people. Not only that, but heat waves can exacerbate disasters such as wildfires and cause significant psychological trauma to humans.

While heatwaves have intensified over the past few years, research into the most extreme heatwaves has come a long way since a heatwave event hit North America's Pacific Northwest in June 2021.

That heatwave, still at record highs, essentially reshaped the field of research on extreme heat, said University of Bristol climate scientist Vikki Thompson. In a study published in May, she and colleagues pointed out [2] that, since 1960, only five heatwaves have been more severe globally than that one, if one looks at the deviation from the climate of the previous 10 years. Just looking at temperature data for the entire Pacific Northwest in the years leading up to that heatwave, she said, the unprecedented heatwave was almost "totally unjustifiable." But it did happen, mainly due to a constant influx of hot air from a high-pressure atmospheric system, combined with hotter-than-usual soil temperatures in much of the region.

beyond expectation

Although the UK heatwave in July was not as severe, it will still go down in history as it made the country aware of the dangers of extreme heat. On July 18 and 19, heat records were broken in many places in the UK, by a full 3 to 4ºC above the previous record (see 'More extreme heat'). 46 weather stations set a new high temperature record of 38.7ºC set just three years ago. It is estimated that hundreds of people may have died as a result.

Source: Met Office

Scientists have foreseen this to some extent. A climate modelling study published two years ago indicated that temperatures above 40ºC could be seen in the UK in the following decades, but this is unlikely [3]. However, that possibility has happened this year, with the UK's high temperature record now at 40.3ºC.The reason why the temperature exceeds the threshold faster than expected may be because climate models cannot capture all the factors that can affect the heat wave, so it is difficult to accurately predict the extreme high temperature in the future [4]. Changes in factors such as land use and irrigation can affect heatwaves in ways that models cannot fully capture, meaning models sometimes misjudge the true impact of climate change.

An analysis published on July 28 by an international team of researchers from World Weather Attribution found that human-caused climate change has increased the incidence of heatwaves in the UK this year by at least 10 times [5]. The study also found that without climate change, heatwaves should have been 2–4ºC cooler.

"More evidence that our models may be missing something," said Peter Stott, a climate scientist at the Met Office, co-author of the 2020 UK study[3]. question."

Erich Fischer, a climate scientist at ETH Zurich, said that, like the 2021 heatwave affecting the Pacific Northwest, the 2022 British heatwave may also allow researchers to find out more quickly what is causing the heatwave than our own. Expected to be more extreme. In a modeling study[6] published last year, Fischer and colleagues projected that the next few decades would see record-breaking climate extremes. "That's exactly what we're seeing now," he said.

Fischer said that studying the magnitude of record-breaking extremes, not just whether records were broken, could help local governments deal with extreme events that may be encountered in the near future.

Dynamic changes

With the exception of the UK, most of Europe has seen several heat waves this year. In fact, Europe has broken heat records more than once in the past five years, says Kai Kornhuber, a climate scientist at Columbia University in New York. His team found that Western Europe is very prone to heat waves [1]. Over the past 40 years, Western Europe has experienced extreme heat three to four times as often as other mid-latitude regions in the Northern Hemisphere.

This may be because the eastward-moving atmospheric jet stream in the North Atlantic often splits in two as it approaches Europe. In this case, the two currents would move the storm away from Europe, allowing the heatwave to form and continue. While it's unclear whether climate change will lead to more of these "twin jets," these types of climate patterns contributed to the July heatwave in Western Europe and are responsible for many recent heat events there.

We may find that similar patterns of atmospheric dynamics are important for revealing what makes high temperature events more extreme than expected, Kornhuber said.

heat wave concurrent

Another distinctive feature of the past few months has been the near simultaneous occurrence of extreme heat in many parts of the world (see "Red Ocean"). At the end of July, China and western North America entered a warmer-than-usual high temperature pattern at about the same time as Europe. A study published in February found that between 1979 and 2019, the frequency of such heatwave concurrent events increased fivefold.

Source: NASA Earth Observatory.

One reason could be atmospheric patterns called Rossby waves, which curve around the Earth and stall weather patterns in specific regions, making those regions prone to extreme heat [8]. The question of whether climate change will make these phenomena more common is unclear. However, concurrent heatwave events that are not related to atmospheric patterns do occur more frequently as the climate warms, says Deepti Singh, a climate scientist at Washington State University in Vancouver. Increase."This year, the heatwave has also arrived earlier in certain regions, such as India and Pakistan, which have been experiencing unbearably high temperatures from March to May this year. Parts of India surpassed 44ºC at the end of March, well ahead of the hottest period in previous years. At least 90 people died as a result. The World Climate Attribution found that climate change increased the probability of this heatwave by 30 times [9].

As global temperatures continue to rise, climate scientists have been stressing the importance of cutting carbon emissions and accelerating human adaptation to extreme temperatures. Stott said the heatwave in the UK had woken up a lot of people to see how vulnerable the country was to extreme heat. Stott, who has worked in climate forecasting for decades, was most surprised to see extreme heat ignite wildfires in central London. "That scene was really shocking."

references:

1. Rousi, E., Kornhuber, K., Beobide-Arsuaga, G., Luo, F. & Coumou, D. Nature Commun. 13, 3851 (2022).

2. Thompson, V. et al. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm6860 (2022).

3. Christidis, N., McCarthy, M. & Stott, PA Nature Commun. 11, 3093 (2020).

4. Van Oldenborgh, GJ et al. Earth's Future 10, e2021EF002271 (2022).

5. Zachariah, M. et al. Without human-caused climate change temperatures of 40 °C in the UK would have been extremely unlikely. (World Weather Attribution, 2022).

6. Fischer, EM, Sippel, S. & Knutti, R. Nature Clim. Change 11, 689–695 (2021).

7. Rogers, CDW, Kornhuber, K., Perkins-Kirkpatrick, SE, Loikith, PC & Singh, DJ Clim. 35, 1063–1078 (2022).

8. Kornhuber, K. et al. Nature Clim. Change 10, 48–53 (2020).

9. Zachariah, M. et al. Climate Change made devastating early heat in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely. (World Weather Attribution, 2022).

The original text was published on the news feature section of Nature on August 4, 2022 under the title Extreme heatwaves: surprising lessons from the record warmth. doi: 10.1038/d41586-022-02114-y

(Original title "Why is it so hot this summer? | "Nature" long article"; The Paper is reprinted with permission)

Related Posts

0 Comments

Write A Comments