Whether the virus can be transmitted in the air in the form of aerosol directly affects its infectious efficiency. In the new issue of the international top medical journal "The Lancet" on June 16, a respiratory team from the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom reported that the possibility of aerosol transmission of monkeypox virus should not be ruled out. In an earlier study, researchers from Tulane University in the United States have demonstrated that monkeypox virus can survive in laboratory-controlled aerosol suspensions for more than 90 hours, and has shown that it may survive in the air environment for a long time. Ability to remain infectious.

As of June 17, the number of monkeypox cases worldwide has reached 2,166, and the epidemic prevention and control situation is becoming increasingly severe. Research and judgment on the transmission route of monkeypox virus will have a crucial impact on the implementation of relevant prevention and control measures.

In February 2013, researchers such as Chad.J.Roy of the Tulane National Primate Research Center in the United States published on the website of the National Institutes of Medicine (NIH) published a paper titled "Susceptibility of Monkeypox Virus Aerosol Suspensions in Spinning Chambers". This is the only article on the aerosol transmission of monkeypox virus among the few literatures on the transmission route of monkeypox virus so far.

In this study, the researchers used a 10.7-liter spin chamber in a tertiary biological cabinet to aerosolize monkeypox virus in the spin chamber, and then cultured by virus plaque assay within 90 hours of virus aging. (Plaque assays, plaques are localized foci of virus on an established monolayer) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to measure the infectivity and concentration of virus in aerosols. The results showed that the concentration of monkeypox virus in the aerosol remained stable for 18-90 hours, and at the same time, the virus had the possibility to remain infectious in the aerosol for more than 90 hours.

"Viral aerosols can have a major impact on public health and infectious dynamics. Once aerosolized, the virus is exposed to various stressors and its integrity and infectious potential can be altered," the researchers said. "While aerosol exposure It is rarely suspected in imported poxvirus outbreaks or naturally occurring cases, but in the case of deliberate poxvirus releases, aerosol exposure remains the most likely route of exposure."

Previous studies have shown that aerosol transmission of viruses depends on the deposition of suspected pathogens in the host's respiratory system, as well as on the integrity and infectious potential of the pathogens. For example, it is hypothesized that variola virus can cause infection with about 100 infectious virus particles, but in reality variola virus can cause disease with 1 infectious virus particle, as long as the virus particle can reach the susceptible area of the lung.

In addition, studies have confirmed that pathogenic viruses in the Poxviridae family can remain infectious for a long time in the environment, and their required infectious concentrations are relatively low, but researchers are concerned about the long-term stability of these viruses in aerosols. Sex is poorly understood.

In this experiment, researchers at Tulane University used a custom-made 10.7-liter spinning chamber constructed from an aluminum cylinder 45.7 cm long and 17.8 cm inner diameter, the chamber was rotated on a horizontal axis at 0.8–1.0 rpm (cycling revolutions per minute). The monkeypox virus strain used in the experiment was a strain (strain Zaire 79) cultivated in Manassas, Virginia. At 20 psi (a unit of pressure, pounds-force per square inch), the researchers atomized the virus suspension with filtered, dry compressed air into the chamber. Each sample was nebulized for 5 minutes, aged for 2 minutes, and then the chamber was closed for 10 minutes of air sampling to obtain initial virus aerosol samples. Next, they performed a second 5-minute nebulization using the same dose of the virus suspension, followed by 2 minutes to 90 hours of aging. Repeat the above steps three times. Between each nebulization, the researchers flushed the air in the chamber with 100 liters of dry filtered air (10 liters/minute for 10 minutes). After air flushing, 2 negative control samples were taken.

At 20 psi (a unit of pressure, pounds-force per square inch), the researchers atomized the virus suspension with filtered, dry compressed air into the chamber. Each sample was nebulized for 5 minutes, aged for 2 minutes, and then the chamber was closed for 10 minutes of air sampling to obtain initial virus aerosol samples. Next, they performed a second 5-minute nebulization using the same dose of the virus suspension, followed by 2 minutes to 90 hours of aging. Repeat the above steps three times. Between each nebulization, the researchers flushed the air in the chamber with 100 liters of dry filtered air (10 liters/minute for 10 minutes). After air flushing, 2 negative control samples were taken.

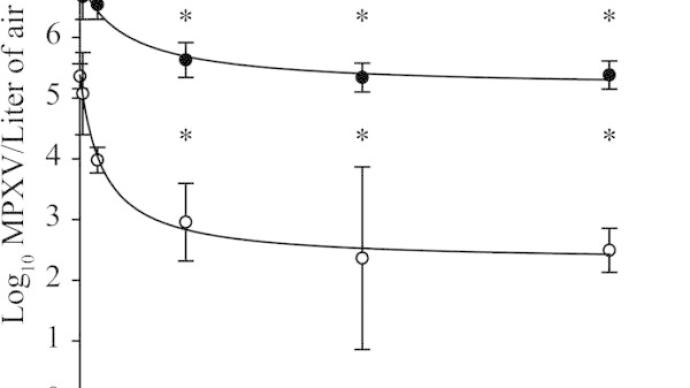

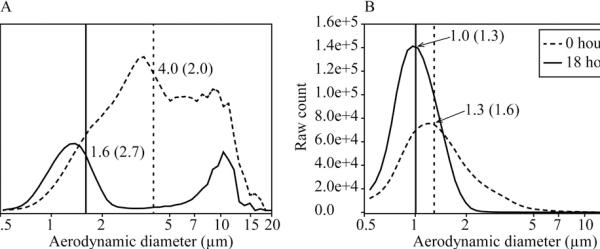

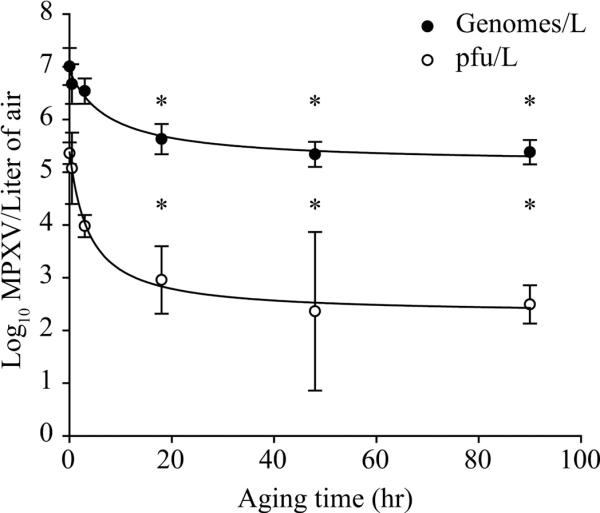

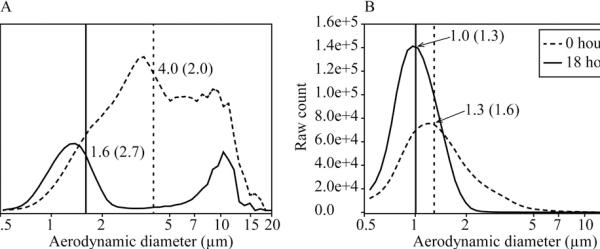

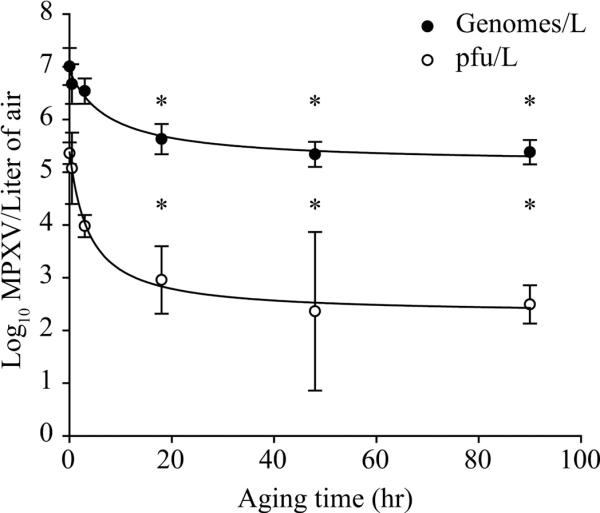

During the aging process of the virus, the temperature of the cabin remained stable at 20°C-22°C, and the relative humidity reached 97%, dropping by about 0.4% per hour. During the testing period, the relative humidity of the cabins was high (60%-97%). At the beginning of atomization, when the mass median diameter of monkeypox virus aerosol (MMAD, the total mass of particles of various sizes smaller than a certain aerodynamic diameter in the particulate matter accounts for 50% of the mass of the total particulate matter, this diameter is called mass. The median diameter) was 4.0µm (micrometer), and it was 1.6µm (micrometer) after aging for 18 hours; the counted median aerodynamic diameter (CMAD) was 1.3µm (micrometer) at the initial stage and 1.0µm (micrometer) after aging for 18 hours. The researchers then used quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) and plaque analysis to reveal detectable viral genomes and infectious virus concentrations in viral aerosol samples. Virus quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) experiments showed that after 2 minutes of aging, the average viral genome concentration per liter of air was 1.2E+07±7.9E+06 genomes, and after 90 hours of aging, the average genome concentration per liter of air was 2.6E+05±1.5E+05 genomes. Viral genome concentrations declined rapidly by 1 log within the first 18 hours of aging and stabilized between 18 and 90 hours. Plaque assay analysis of viral aerosol samples showed that the infectious virus concentration decreased by two logs within the first 18 hours and remained stable for the following 90 hours.

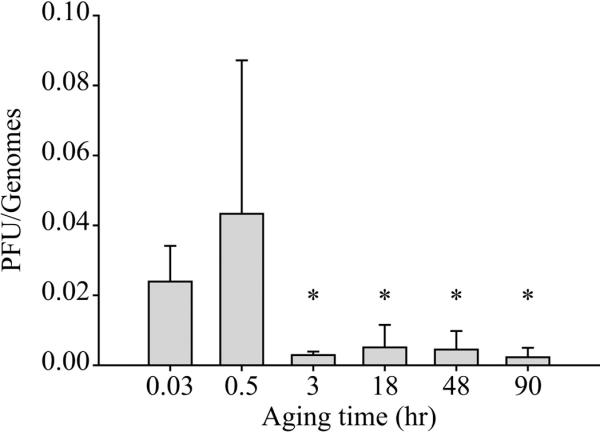

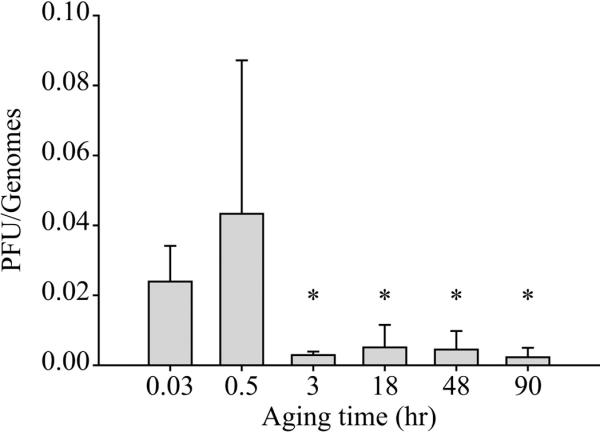

The researchers then used quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) and plaque analysis to reveal detectable viral genomes and infectious virus concentrations in viral aerosol samples. Virus quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) experiments showed that after 2 minutes of aging, the average viral genome concentration per liter of air was 1.2E+07±7.9E+06 genomes, and after 90 hours of aging, the average genome concentration per liter of air was 2.6E+05±1.5E+05 genomes. Viral genome concentrations declined rapidly by 1 log within the first 18 hours of aging and stabilized between 18 and 90 hours. Plaque assay analysis of viral aerosol samples showed that the infectious virus concentration decreased by two logs within the first 18 hours and remained stable for the following 90 hours.  The researchers also calculated the fraction of the viral genome that correlated with plaque formation by the ratio of plaque formation volume (PFU) to viral genome for each viral aerosol sample. This ratio was not significantly different between 2 and 30 minutes of aging. After 3 hours, the ratio dropped by a factor of 10. This ratio decreased significantly at 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours compared with 2 minutes (P<0.05). There were no significant differences between 30 minutes, 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours.

The researchers also calculated the fraction of the viral genome that correlated with plaque formation by the ratio of plaque formation volume (PFU) to viral genome for each viral aerosol sample. This ratio was not significantly different between 2 and 30 minutes of aging. After 3 hours, the ratio dropped by a factor of 10. This ratio decreased significantly at 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours compared with 2 minutes (P<0.05). There were no significant differences between 30 minutes, 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours.  After aging in a rotating chamber for 90 hours, the researchers recovered the infectious virus from the aerosol suspension. This suggests that monkeypox virus survives in aerosol particles for more than 90 hours and may remain infectious for long periods of time in the environment.

After aging in a rotating chamber for 90 hours, the researchers recovered the infectious virus from the aerosol suspension. This suggests that monkeypox virus survives in aerosol particles for more than 90 hours and may remain infectious for long periods of time in the environment.

The researchers acknowledge that the study has certain limitations. "The real environmental conditions are complex and changeable, and in an uncontrolled environment, the actual suspension time of the virus may be difficult to predict," the researchers said. Changes are more sensitive. Humidity and temperature will greatly affect the physical dynamics of aerosols, the integrity of viral particles, and the likelihood of infection once they enter the host respiratory system."

On the other hand, the process of nebulization and sampling may also damage the virus, causing some viral particles to be inactivated. Therefore, the aerosol stability and infectivity of monkeypox virus may be underestimated. Ideally, viral aerosol efficiency should be studied in naturally occurring viral aerosols shed from infected hosts, or in secondary aerosols produced by infected organisms. However, viruses from these sources are highly variable, making the study of naturally occurring viral bioaerosols extremely difficult.

In conclusion, the researchers stated, "The longevity of monkeypox virus in laboratory-controlled aerosols suggests that the virus may remain infectious for long periods of time in the environment, the least likely route of transmission during epidemics. Routes of exposure identified. For this, we need strict respiratory protection of the population and preventive measures such as ring vaccination.”

As of June 17, the number of monkeypox cases worldwide has reached 2,166, and the epidemic prevention and control situation is becoming increasingly severe. Research and judgment on the transmission route of monkeypox virus will have a crucial impact on the implementation of relevant prevention and control measures.

In February 2013, researchers such as Chad.J.Roy of the Tulane National Primate Research Center in the United States published on the website of the National Institutes of Medicine (NIH) published a paper titled "Susceptibility of Monkeypox Virus Aerosol Suspensions in Spinning Chambers". This is the only article on the aerosol transmission of monkeypox virus among the few literatures on the transmission route of monkeypox virus so far.

In this study, the researchers used a 10.7-liter spin chamber in a tertiary biological cabinet to aerosolize monkeypox virus in the spin chamber, and then cultured by virus plaque assay within 90 hours of virus aging. (Plaque assays, plaques are localized foci of virus on an established monolayer) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to measure the infectivity and concentration of virus in aerosols. The results showed that the concentration of monkeypox virus in the aerosol remained stable for 18-90 hours, and at the same time, the virus had the possibility to remain infectious in the aerosol for more than 90 hours.

"Viral aerosols can have a major impact on public health and infectious dynamics. Once aerosolized, the virus is exposed to various stressors and its integrity and infectious potential can be altered," the researchers said. "While aerosol exposure It is rarely suspected in imported poxvirus outbreaks or naturally occurring cases, but in the case of deliberate poxvirus releases, aerosol exposure remains the most likely route of exposure."

Previous studies have shown that aerosol transmission of viruses depends on the deposition of suspected pathogens in the host's respiratory system, as well as on the integrity and infectious potential of the pathogens. For example, it is hypothesized that variola virus can cause infection with about 100 infectious virus particles, but in reality variola virus can cause disease with 1 infectious virus particle, as long as the virus particle can reach the susceptible area of the lung.

In addition, studies have confirmed that pathogenic viruses in the Poxviridae family can remain infectious for a long time in the environment, and their required infectious concentrations are relatively low, but researchers are concerned about the long-term stability of these viruses in aerosols. Sex is poorly understood.

In this experiment, researchers at Tulane University used a custom-made 10.7-liter spinning chamber constructed from an aluminum cylinder 45.7 cm long and 17.8 cm inner diameter, the chamber was rotated on a horizontal axis at 0.8–1.0 rpm (cycling revolutions per minute). The monkeypox virus strain used in the experiment was a strain (strain Zaire 79) cultivated in Manassas, Virginia.

At 20 psi (a unit of pressure, pounds-force per square inch), the researchers atomized the virus suspension with filtered, dry compressed air into the chamber. Each sample was nebulized for 5 minutes, aged for 2 minutes, and then the chamber was closed for 10 minutes of air sampling to obtain initial virus aerosol samples. Next, they performed a second 5-minute nebulization using the same dose of the virus suspension, followed by 2 minutes to 90 hours of aging. Repeat the above steps three times. Between each nebulization, the researchers flushed the air in the chamber with 100 liters of dry filtered air (10 liters/minute for 10 minutes). After air flushing, 2 negative control samples were taken.

At 20 psi (a unit of pressure, pounds-force per square inch), the researchers atomized the virus suspension with filtered, dry compressed air into the chamber. Each sample was nebulized for 5 minutes, aged for 2 minutes, and then the chamber was closed for 10 minutes of air sampling to obtain initial virus aerosol samples. Next, they performed a second 5-minute nebulization using the same dose of the virus suspension, followed by 2 minutes to 90 hours of aging. Repeat the above steps three times. Between each nebulization, the researchers flushed the air in the chamber with 100 liters of dry filtered air (10 liters/minute for 10 minutes). After air flushing, 2 negative control samples were taken.During the aging process of the virus, the temperature of the cabin remained stable at 20°C-22°C, and the relative humidity reached 97%, dropping by about 0.4% per hour. During the testing period, the relative humidity of the cabins was high (60%-97%). At the beginning of atomization, when the mass median diameter of monkeypox virus aerosol (MMAD, the total mass of particles of various sizes smaller than a certain aerodynamic diameter in the particulate matter accounts for 50% of the mass of the total particulate matter, this diameter is called mass. The median diameter) was 4.0µm (micrometer), and it was 1.6µm (micrometer) after aging for 18 hours; the counted median aerodynamic diameter (CMAD) was 1.3µm (micrometer) at the initial stage and 1.0µm (micrometer) after aging for 18 hours.

The researchers then used quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) and plaque analysis to reveal detectable viral genomes and infectious virus concentrations in viral aerosol samples. Virus quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) experiments showed that after 2 minutes of aging, the average viral genome concentration per liter of air was 1.2E+07±7.9E+06 genomes, and after 90 hours of aging, the average genome concentration per liter of air was 2.6E+05±1.5E+05 genomes. Viral genome concentrations declined rapidly by 1 log within the first 18 hours of aging and stabilized between 18 and 90 hours. Plaque assay analysis of viral aerosol samples showed that the infectious virus concentration decreased by two logs within the first 18 hours and remained stable for the following 90 hours.

The researchers then used quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) and plaque analysis to reveal detectable viral genomes and infectious virus concentrations in viral aerosol samples. Virus quantitative polymerase chain (qPCR) experiments showed that after 2 minutes of aging, the average viral genome concentration per liter of air was 1.2E+07±7.9E+06 genomes, and after 90 hours of aging, the average genome concentration per liter of air was 2.6E+05±1.5E+05 genomes. Viral genome concentrations declined rapidly by 1 log within the first 18 hours of aging and stabilized between 18 and 90 hours. Plaque assay analysis of viral aerosol samples showed that the infectious virus concentration decreased by two logs within the first 18 hours and remained stable for the following 90 hours.  The researchers also calculated the fraction of the viral genome that correlated with plaque formation by the ratio of plaque formation volume (PFU) to viral genome for each viral aerosol sample. This ratio was not significantly different between 2 and 30 minutes of aging. After 3 hours, the ratio dropped by a factor of 10. This ratio decreased significantly at 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours compared with 2 minutes (P<0.05). There were no significant differences between 30 minutes, 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours.

The researchers also calculated the fraction of the viral genome that correlated with plaque formation by the ratio of plaque formation volume (PFU) to viral genome for each viral aerosol sample. This ratio was not significantly different between 2 and 30 minutes of aging. After 3 hours, the ratio dropped by a factor of 10. This ratio decreased significantly at 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours compared with 2 minutes (P<0.05). There were no significant differences between 30 minutes, 3 hours, 18 hours, 48 hours and 90 hours.  After aging in a rotating chamber for 90 hours, the researchers recovered the infectious virus from the aerosol suspension. This suggests that monkeypox virus survives in aerosol particles for more than 90 hours and may remain infectious for long periods of time in the environment.

After aging in a rotating chamber for 90 hours, the researchers recovered the infectious virus from the aerosol suspension. This suggests that monkeypox virus survives in aerosol particles for more than 90 hours and may remain infectious for long periods of time in the environment.The researchers acknowledge that the study has certain limitations. "The real environmental conditions are complex and changeable, and in an uncontrolled environment, the actual suspension time of the virus may be difficult to predict," the researchers said. Changes are more sensitive. Humidity and temperature will greatly affect the physical dynamics of aerosols, the integrity of viral particles, and the likelihood of infection once they enter the host respiratory system."

On the other hand, the process of nebulization and sampling may also damage the virus, causing some viral particles to be inactivated. Therefore, the aerosol stability and infectivity of monkeypox virus may be underestimated. Ideally, viral aerosol efficiency should be studied in naturally occurring viral aerosols shed from infected hosts, or in secondary aerosols produced by infected organisms. However, viruses from these sources are highly variable, making the study of naturally occurring viral bioaerosols extremely difficult.

In conclusion, the researchers stated, "The longevity of monkeypox virus in laboratory-controlled aerosols suggests that the virus may remain infectious for long periods of time in the environment, the least likely route of transmission during epidemics. Routes of exposure identified. For this, we need strict respiratory protection of the population and preventive measures such as ring vaccination.”

Related Posts

0 Comments

Write A Comments