“In recent years, Chinese scientists have produced the largest number of papers in the world, but our innovation, particularly original innovation, is still far from sufficient. Where does the problem lie? Is it that we scientists are too incompetent to innovate? Or are we just too lazy to make the effort?” On the afternoon of September 23, the 88-year-old academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and professor at Tongji University, Wang Pinxian, raised this question at the launch of his new book, Science and Culture: Academicians Discuss Original Innovation.

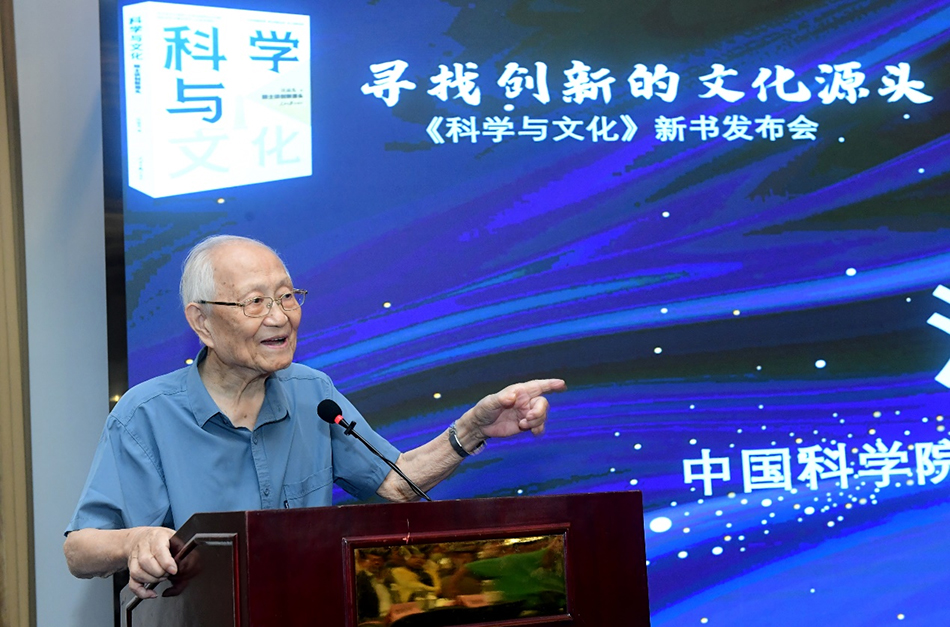

On the afternoon of September 23, Wang Pinxian, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and professor at Tongji University, speaks at the launch of his new book Science and Culture: Academicians Discuss Original Innovation.

Wang Pinxian: Where Are the Barriers to Innovation?

“I want to place this big question mark in front of more people—where are the barriers to innovation?” Wang stated during an interview with reporters on the afternoon of the 23rd.

“I believe the barrier to innovation is culture,” he explained. “The soil for scientific innovation is also culture. However, there are indeed elements within our traditional culture that are not conducive to scientific innovation. Present-day social culture also has its contradictions. For instance, when it comes to writing articles, they often consist of clichéd phrases; when discussing viewpoints or arguments, some people tend to follow the authority and look to leadership. Such a culture cannot foster innovation.” “Where exactly is the intersection point between our traditional culture and modern science? Where are the contradictions? I hope this question will be taken seriously; that is the purpose of writing this book.”

His reflections on the issue of “barriers to innovation” originated from the national science and technology conference in 2006, which proposed the idea of “building an innovative country.” “I was particularly inspired by it. But how can we become an innovative country? Therefore, I initiated a discussion in the newspapers about the barriers to innovation. However, the discussions did not go very deep. These problems are not easy to solve,” he said.

He has continuously sought to answer this question.

Two years ago, he wrote an article for The Paper, stating, “Scientific innovation requires a cultural foundation.” “We must promote the integration of Eastern culture and modern science.”

Previously, he offered two rounds of courses on “Science and Culture” at Tongji University, aiming to promote the fusion of science and culture, and create an environment for innovation.

“I believe that the relationship between science and culture is such that—without culture, innovation is impossible.” He added, “There are two types of science: one is original innovation, and the other is application and imitation. Original innovation places very high demands on culture,” Wang said.

“I advocate that China should promote this direction—creating a new civilization that integrates land and sea, East and West in the new era, this is our task today. If this book can offer some inspiration for the culture of innovation and gain some societal attention, then that would be the greatest reward for this book,” Wang expressed.

Experts: A More Innovative Shanghai Should Establish a Cultural Center

At the seminar on “Finding the Cultural Roots of Innovation,” several academicians and experts reiterated the need for Shanghai to further develop its distinctive Haipai culture and enhance the functions and status of its cultural center in order to promote innovation.

Zheng Shiling, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, director of the Architecture and Urban Space Research Institute at Tongji University, and an architect, remarked during the discussion, “When discussing the characteristics of this city, I once advocated for identifying it as a ‘Cultural Center.’”

Wang Pinxian commented, “What are the characteristics of Shanghai's Haipai culture? Haipai culture often emerges without adhering to ‘norms.’ Many films from the 1930s that we see today were shot in Shanghai, and many old songs also originated there. I believe that in terms of scientific and cultural development, Shanghai should highlight new features of Haipai civilization.”

Wang further analyzed the roots of cultural differences between the East and West, stating, “The source of these differences stems from the distinctions between oceanic civilization and continental civilization. Two thousand five hundred years ago, an oceanic civilization emerged in ancient Greece in the Mediterranean, while a continental civilization emerged in the Yellow River basin. Each civilization has its own merits. Continental civilization emphasizes collective and family values, tradition, and stability. Oceanic civilization values the individual and exploration. In the last few hundred years, when the two civilizations collided, the continental civilization has lost.”

“An American professor visiting remarked that he found it strange, saying, ‘Western wars are always related to religion. Yours are not like that.’ We (China) indeed possess a unique culture that is not easily understood by Westerners. China has the world’s only ancient culture that is still active today. While continental culture allows for inclusivity, oceanic civilization tends to be competitive.”

“In the past, oceanic and continental civilizations were separate, and the two economies were also distinct. But now, the economies of the ocean and the continent are increasingly intertwined. I think if the economy is integrated, then culture must inevitably also converge.”

Wang Pinxian stated, “China can embody both continental (civilization) and oceanic (civilization). How to establish a civilization that balances both sea and land is our mission.”

Wang Pinxian, academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and professor at the College of Marine and Earth Sciences at Tongji University.

Public information shows that Wang Pinxian, born in 1936 in Shanghai, is a marine geologist and a professor at the College of Marine and Earth Sciences at Tongji University. He graduated from the Department of Geology at Moscow University in 1960 and conducted research at Kiel University in Germany on a Humboldt Scholarship from 1981 to 1982. He specializes in paleoceanography and micropaleontology, primarily studying climate evolution and the geology of the South China Sea, and he is dedicated to advancing deep-sea technology in China. He has pioneered research in paleoceanography in his country and proposed new concepts such as climate-driven evolution in the tropics. In 1999, he led China’s first ocean drilling expedition in the South China Sea, paving the way for deep-sea scientific drilling in China; from 2011 to 2018, he headed the National Natural Science Fund’s major research program on “Deep Sea Processes and Evolution in the South China Sea,” marking China's first large-scale fundamental research program in marine science. In 2018, he discovered deep-water coral forests in the South China Sea and actively promoted deep-sea observations, contributing to the establishment of a large-scale scientific project for undersea observation in China.