The mystery has gained global attention in the past two months since the UK reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) a significant increase in acute hepatitis cases of unknown cause in children in early April. Many countries around the world have begun to report similar cases in their own countries, but are these cases different from previous clinical cases of unexplained childhood hepatitis? What is the cause? Many issues need to be further studied.

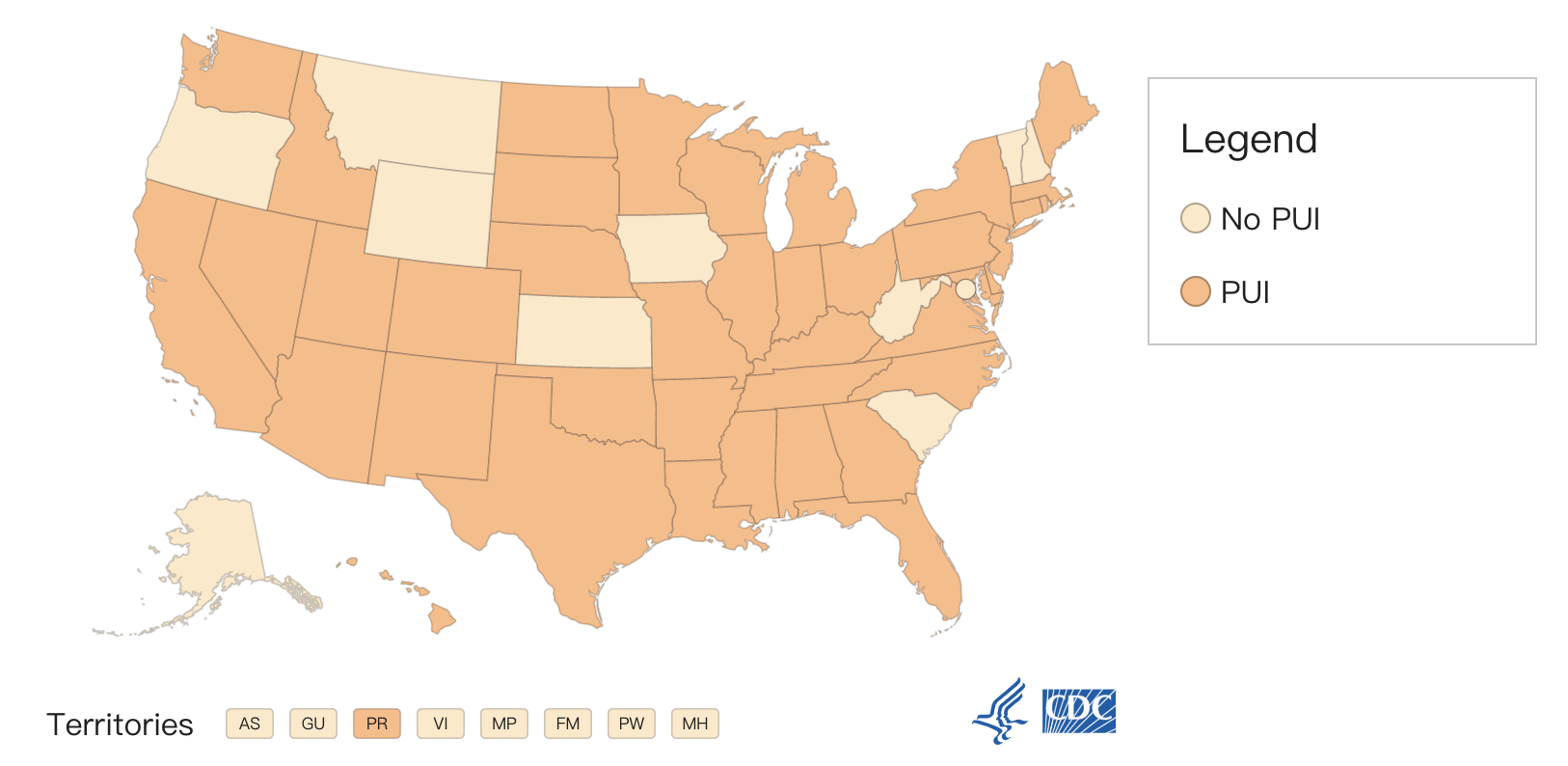

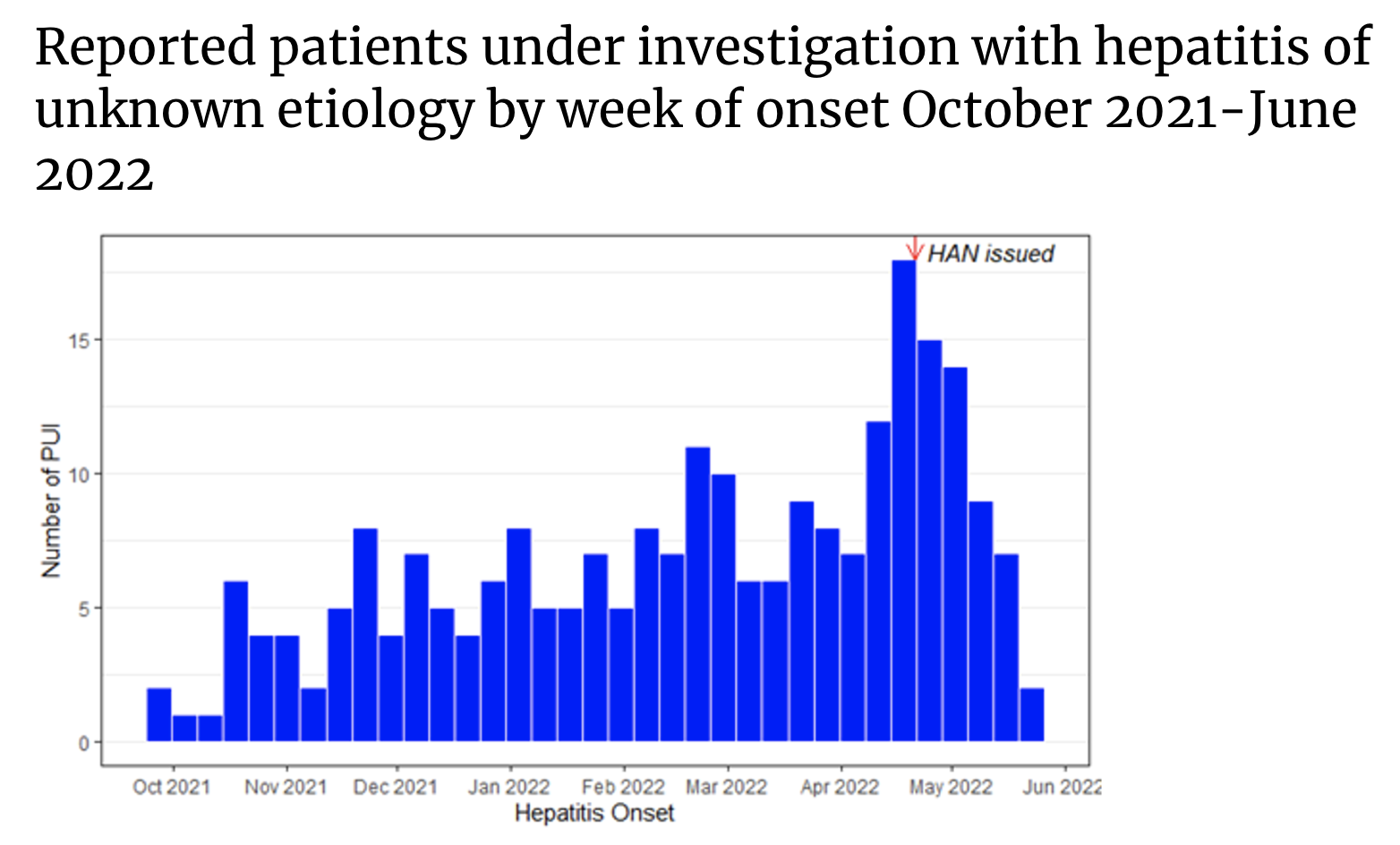

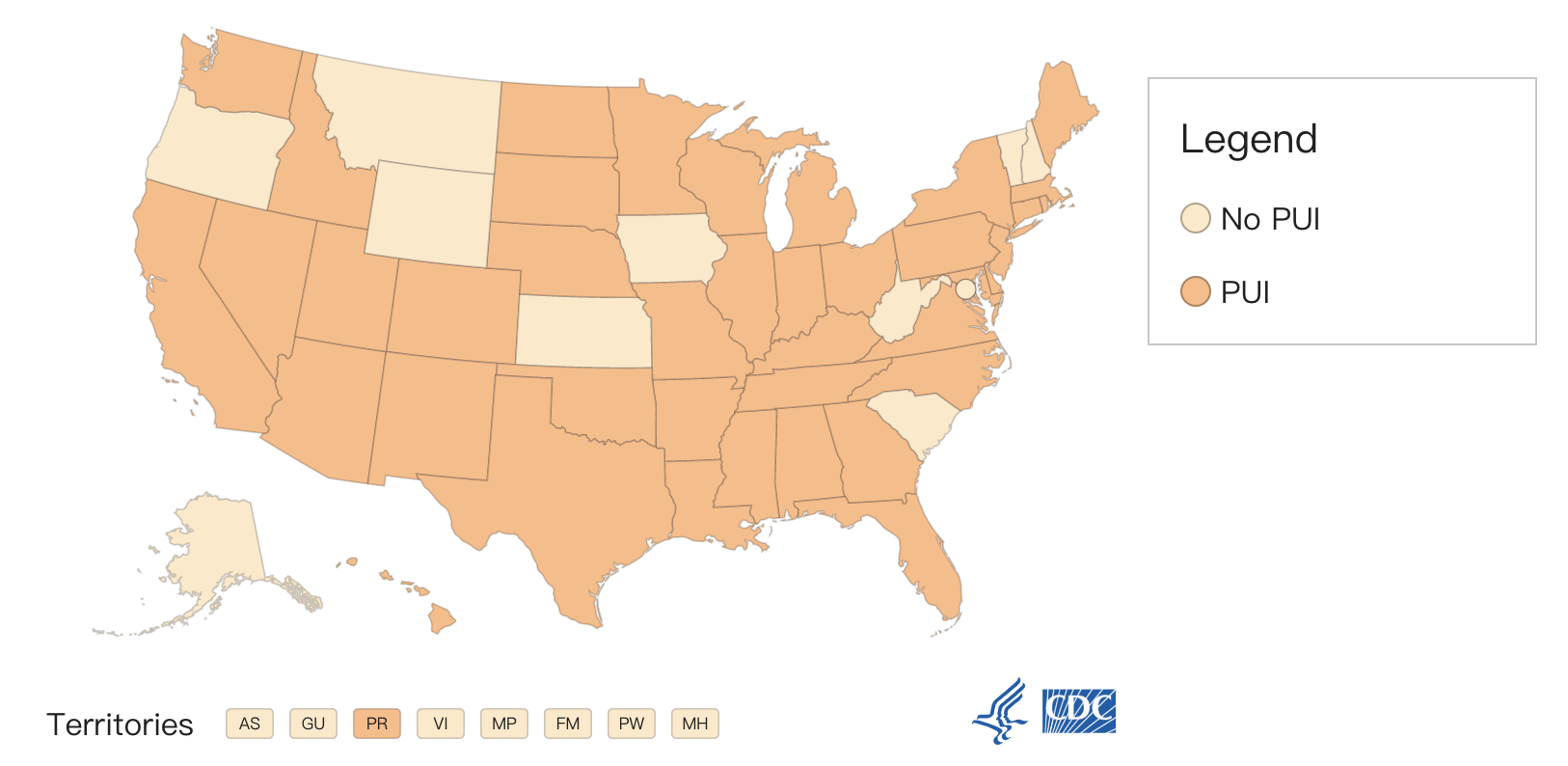

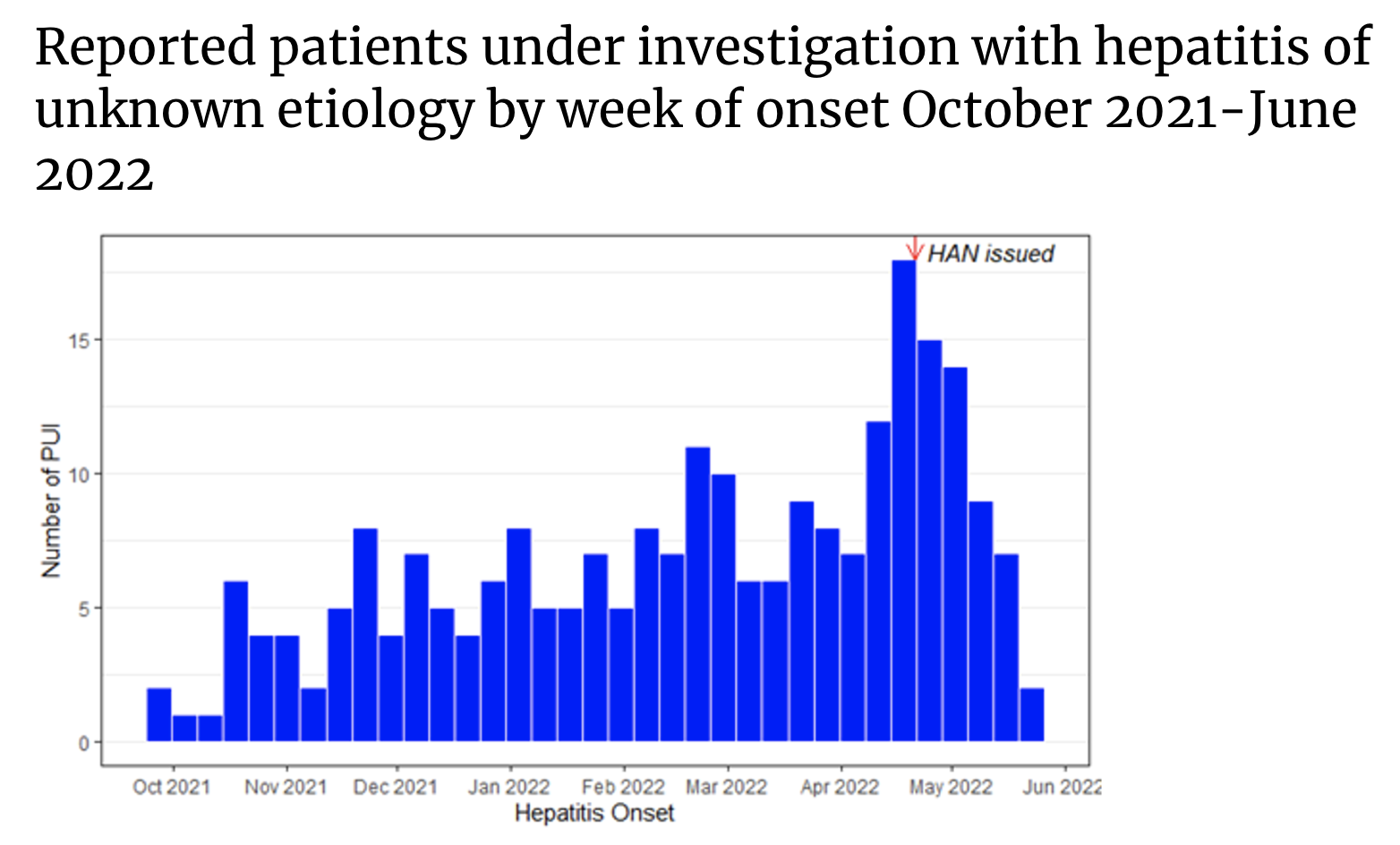

According to the latest technical report released by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of June 15, 2022, a total of 290 patients under investigation (PUI) have been reported in 41 states and jurisdictions, with the onset date from October 1, 2021. The current definition of a patient under investigation remains: as of October 1, 2021, younger than 10 years of age, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (>500 U/L), Children with unknown etiology of hepatitis (with or without adenovirus test results). The median age of these patients was 2 years (0-9 years), and 48% were boys. To date, 17 have required liver transplants and 11 children have died. In the week leading up to June 15, 16 new cases of investigational patients were reported. Among them, 9 cases developed symptoms between June 1 and 15, and the remaining 7 cases appeared earlier.

The median age of these patients was 2 years (0-9 years), and 48% were boys. To date, 17 have required liver transplants and 11 children have died. In the week leading up to June 15, 16 new cases of investigational patients were reported. Among them, 9 cases developed symptoms between June 1 and 15, and the remaining 7 cases appeared earlier.

Hepatitis, or inflammation of the liver, is often caused by viral infections, alcohol, toxins, drugs, and certain diseases. According to the CDC, the most common causes of viral hepatitis in the United States are hepatitis A, B, and C. Signs and symptoms of hepatitis include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, light stools, joint pain, and jaundice. The treatment of hepatitis depends on the underlying cause.

For these children with unexplained hepatitis who have been included since October 1, 2021, the CDC said it is investigating several aetiological hypotheses, especially the possible association with adenovirus type 41 infection. In 197 of these patients, any type of specimen (blood, respiratory specimen, stool) was tested for adenovirus, and 47% were found to be positive for adenovirus.

Adenovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus that spreads through close personal contact, respiratory droplets, and pollutants. There are more than 50 different adenoviruses that can cause infection in humans, most commonly respiratory disease, but certain types of adenoviruses can also cause other diseases, such as gastroenteritis, conjunctivitis, cystitis, and, less commonly, the nervous system disease. There is no specific treatment for adenovirus infection.

Among them, adenovirus type 41 usually causes acute gastroenteritis in children, with typical manifestations of diarrhea, vomiting, and fever; often accompanied by respiratory symptoms.

Notably, although there have been case reports linking hepatitis in immunocompromised children with adenovirus type 41 infection, it is unclear whether adenovirus type 41 is the cause of hepatitis in other healthy children. These children, who have recently raised concerns, had previously been largely healthy.

The CDC said they are also evaluating other hypotheses beyond adenovirus, including whether some children, due to age or other factors, show atypical responses to their first adenovirus (or other virus) infection, thereby cause hepatitis? In the reported survey patients, were there multiple factors contributing to the disease rather than a single primary driver? Is acute hepatitis in children an autoimmune phenomenon or superantigen response due to persistent or previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 and adenovirus? Is acute hepatitis in children a manifestation of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)? Is acute hepatitis in children caused by the environment or by ingested toxins?

Identifying the cause of acute hepatitis in children remains a high priority, the CDC said. The center and its partners are conducting extensive laboratory testing, including adenovirus infection, and planning epidemiological and laboratory studies to test the etiological hypothesis under investigation.

They also conducted a risk assessment of the disease, saying that the current incidence of acute hepatitis in children is no higher than pre-pandemic baseline levels, and severe outcomes are uncommon. However, the CDC encourages parents and caregivers to be aware of symptoms of hepatitis in children, especially jaundice. It is worth noting that on June 14, local time, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also released a preliminary survey, which showed that compared with the baseline before the COVID-19 pandemic, between October 2021 and There was no increase in weekly hepatitis-related emergency room visits among children aged 0-4 or 5-11 during March 2022. In addition, between April 2020 and September 2021, the number of tests and the percentage of 40/41 adenovirus positivity decreased, but between October 2021 and March 2022, 0-4, 5-9 The percentage of adenovirus 40/41 positive specimens in both age groups returned to pre-pandemic levels but did not exceed.

It is worth noting that on June 14, local time, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also released a preliminary survey, which showed that compared with the baseline before the COVID-19 pandemic, between October 2021 and There was no increase in weekly hepatitis-related emergency room visits among children aged 0-4 or 5-11 during March 2022. In addition, between April 2020 and September 2021, the number of tests and the percentage of 40/41 adenovirus positivity decreased, but between October 2021 and March 2022, 0-4, 5-9 The percentage of adenovirus 40/41 positive specimens in both age groups returned to pre-pandemic levels but did not exceed.

While this analysis cannot conclusively confirm or refute a potential link between childhood hepatitis and adenovirus, it provides a useful context for ongoing research, the report argues. The report also emphasizes that ongoing trend assessments and enhanced epidemiological investigations will help understand reported cases of acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children in the United States.

According to the latest technical report released by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of June 15, 2022, a total of 290 patients under investigation (PUI) have been reported in 41 states and jurisdictions, with the onset date from October 1, 2021. The current definition of a patient under investigation remains: as of October 1, 2021, younger than 10 years of age, elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (>500 U/L), Children with unknown etiology of hepatitis (with or without adenovirus test results).

The median age of these patients was 2 years (0-9 years), and 48% were boys. To date, 17 have required liver transplants and 11 children have died. In the week leading up to June 15, 16 new cases of investigational patients were reported. Among them, 9 cases developed symptoms between June 1 and 15, and the remaining 7 cases appeared earlier.

The median age of these patients was 2 years (0-9 years), and 48% were boys. To date, 17 have required liver transplants and 11 children have died. In the week leading up to June 15, 16 new cases of investigational patients were reported. Among them, 9 cases developed symptoms between June 1 and 15, and the remaining 7 cases appeared earlier.Hepatitis, or inflammation of the liver, is often caused by viral infections, alcohol, toxins, drugs, and certain diseases. According to the CDC, the most common causes of viral hepatitis in the United States are hepatitis A, B, and C. Signs and symptoms of hepatitis include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, light stools, joint pain, and jaundice. The treatment of hepatitis depends on the underlying cause.

For these children with unexplained hepatitis who have been included since October 1, 2021, the CDC said it is investigating several aetiological hypotheses, especially the possible association with adenovirus type 41 infection. In 197 of these patients, any type of specimen (blood, respiratory specimen, stool) was tested for adenovirus, and 47% were found to be positive for adenovirus.

Adenovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus that spreads through close personal contact, respiratory droplets, and pollutants. There are more than 50 different adenoviruses that can cause infection in humans, most commonly respiratory disease, but certain types of adenoviruses can also cause other diseases, such as gastroenteritis, conjunctivitis, cystitis, and, less commonly, the nervous system disease. There is no specific treatment for adenovirus infection.

Among them, adenovirus type 41 usually causes acute gastroenteritis in children, with typical manifestations of diarrhea, vomiting, and fever; often accompanied by respiratory symptoms.

Notably, although there have been case reports linking hepatitis in immunocompromised children with adenovirus type 41 infection, it is unclear whether adenovirus type 41 is the cause of hepatitis in other healthy children. These children, who have recently raised concerns, had previously been largely healthy.

The CDC said they are also evaluating other hypotheses beyond adenovirus, including whether some children, due to age or other factors, show atypical responses to their first adenovirus (or other virus) infection, thereby cause hepatitis? In the reported survey patients, were there multiple factors contributing to the disease rather than a single primary driver? Is acute hepatitis in children an autoimmune phenomenon or superantigen response due to persistent or previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 and adenovirus? Is acute hepatitis in children a manifestation of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)? Is acute hepatitis in children caused by the environment or by ingested toxins?

Identifying the cause of acute hepatitis in children remains a high priority, the CDC said. The center and its partners are conducting extensive laboratory testing, including adenovirus infection, and planning epidemiological and laboratory studies to test the etiological hypothesis under investigation.

They also conducted a risk assessment of the disease, saying that the current incidence of acute hepatitis in children is no higher than pre-pandemic baseline levels, and severe outcomes are uncommon. However, the CDC encourages parents and caregivers to be aware of symptoms of hepatitis in children, especially jaundice.

It is worth noting that on June 14, local time, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also released a preliminary survey, which showed that compared with the baseline before the COVID-19 pandemic, between October 2021 and There was no increase in weekly hepatitis-related emergency room visits among children aged 0-4 or 5-11 during March 2022. In addition, between April 2020 and September 2021, the number of tests and the percentage of 40/41 adenovirus positivity decreased, but between October 2021 and March 2022, 0-4, 5-9 The percentage of adenovirus 40/41 positive specimens in both age groups returned to pre-pandemic levels but did not exceed.

It is worth noting that on June 14, local time, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also released a preliminary survey, which showed that compared with the baseline before the COVID-19 pandemic, between October 2021 and There was no increase in weekly hepatitis-related emergency room visits among children aged 0-4 or 5-11 during March 2022. In addition, between April 2020 and September 2021, the number of tests and the percentage of 40/41 adenovirus positivity decreased, but between October 2021 and March 2022, 0-4, 5-9 The percentage of adenovirus 40/41 positive specimens in both age groups returned to pre-pandemic levels but did not exceed.While this analysis cannot conclusively confirm or refute a potential link between childhood hepatitis and adenovirus, it provides a useful context for ongoing research, the report argues. The report also emphasizes that ongoing trend assessments and enhanced epidemiological investigations will help understand reported cases of acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children in the United States.

Comments