The latest issue of Emerging Infectious Diseases, an academic journal of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), published a study revealing a suspected case of cat-to-human transmission of the new coronavirus in Thailand.  Through epidemiological investigations and viral genome sequencing, the study concluded that a 32-year-old healthy female veterinarian in Thailand was infected with the new coronavirus by a cat. The cat was infected with the new crown by its owner. The corresponding authors of the study are from the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, and the Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

Through epidemiological investigations and viral genome sequencing, the study concluded that a 32-year-old healthy female veterinarian in Thailand was infected with the new coronavirus by a cat. The cat was infected with the new crown by its owner. The corresponding authors of the study are from the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, and the Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

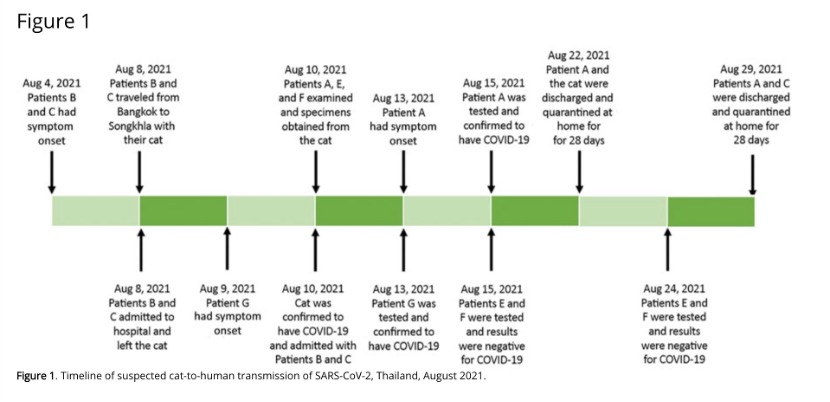

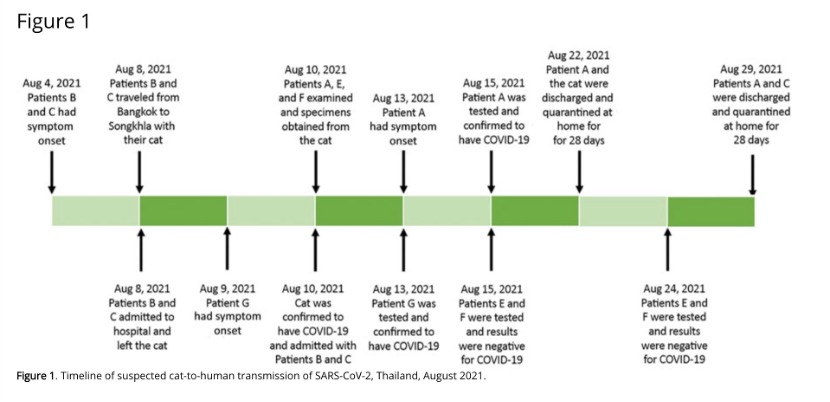

Between July and September 2021, the COVID-19 outbreak in Thailand is shifting from an alpha variant to a delta variant. On August 15, 2021, a 32-year-old healthy female veterinarian, Patient A, visited the Prince of Songkhla University Hospital in Hat Yai District, Songkhla Province, in the prosperous Songkhla Province in southern Thailand.

Patient A, living alone in a dormitory on campus, sought medical attention because of fever, runny nose, and a productive cough that lasted for 2 days. Physical examination was acceptable, but chest X-ray showed unremarkable findings. When asked about her medical history, she stated that 5 days ago, she and 2 other veterinarians (E and F) examined a cat. This cat was owned by a father and son duo (patients B and C).

Patient B, 32, and Patient C, 64, live in Bangkok, the capital of Thailand. On August 7, they tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid, but because there was no hospital bed in Bangkok, the father and son were transferred to the Prince of Songkhla University Hospital. On August 8, 2021, patients B and C were transported by ambulance along with their cats, a 20-hour drive, a distance of 900 km.

Patient A developed symptoms 3 days after being in contact with the cat, but did not seek medical advice until the cat's nucleic acid test came back positive on August 15. After investigation, patient A's nasopharyngeal swab tested positive for the new crown. Patients A, B and C and the cat were taken to hospital for isolation. Nasopharyngeal swabs from E and F were negative.

None of the close contacts of patient A were tested positive for the new coronavirus. A contact tracing investigation of all 30 staff working at the veterinary hospital found that 1 other veterinarian (patient G) had been in contact with other COVID-19 patients, working in the large animal department. Patient G developed a fever 1 day before the cat's arrival and tested positive for 2019-nCoV on August 13, 2021. Patient G reported no direct or indirect contact with cats or patients A, E, or F.

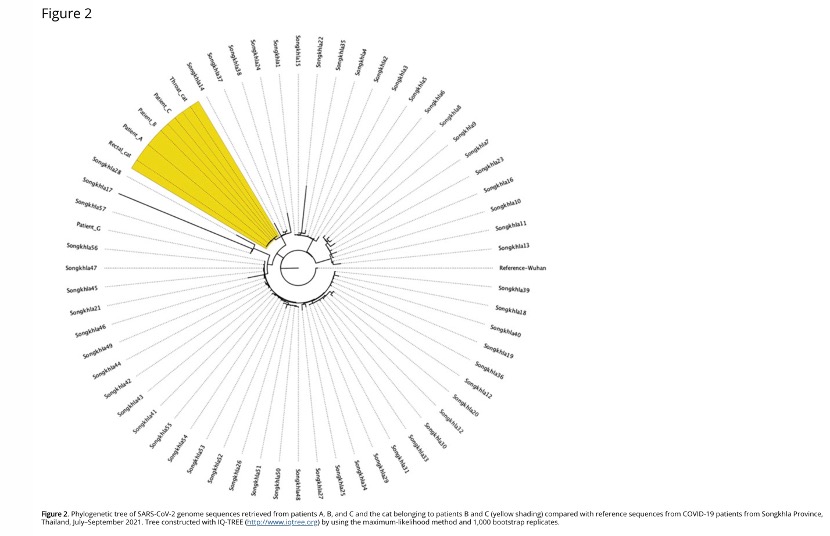

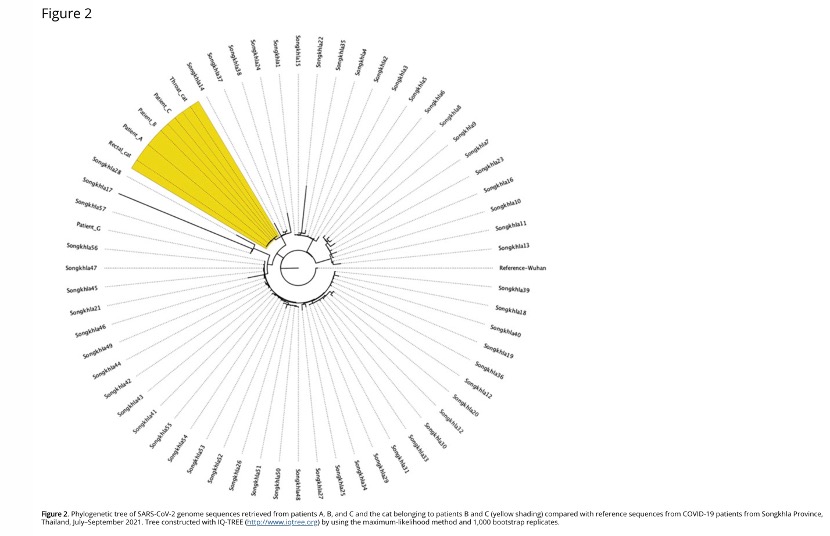

The researchers further sequenced the new coronaviruses of patient G and patients A, B, C, and cats. The researchers also tested SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA from other Songkhla patients before genotyping. By visualizing the phylogenetic tree, the researchers found that the genomes of patients B, C, and cats were the same as those of patient A, but they were different from those of other patients in the same province.

As shown below:

The same SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence obtained from patient A and sequences obtained from the cat and its 2 owners, as well as the temporal overlap of animal and human infections, suggest that this series of infections is epidemiologically, according to the investigators. is relevant. Since patient A had not met patient B or C before, when the cat sneezed, she may have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 by the cat. The genome sequence was different from that of patient G and other sequences circulating in the same province, and by using the pairwise distance formula, the researchers ruled out the possibility of external transmission. The alpha variant spread widely in Songkhla until the end of July 2021; but in Bangkok, the delta variant has been very common since early July 2021.

The same SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence obtained from patient A and sequences obtained from the cat and its 2 owners, as well as the temporal overlap of animal and human infections, suggest that this series of infections is epidemiologically, according to the investigators. is relevant. Since patient A had not met patient B or C before, when the cat sneezed, she may have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 by the cat. The genome sequence was different from that of patient G and other sequences circulating in the same province, and by using the pairwise distance formula, the researchers ruled out the possibility of external transmission. The alpha variant spread widely in Songkhla until the end of July 2021; but in Bangkok, the delta variant has been very common since early July 2021.

The researchers suggest that the chain of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the cluster likely started in Bangkok. Cats are known to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially during close interactions with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2-infected humans. Because of the relatively short incubation and infectious periods of an infected cat, this cat may have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 less than a week before it could potentially transmit the disease to Patient A.

While direct or indirect (contaminant) contacts are also potential routes of transmission to Patient A, these are less likely. The researchers analyzed because she wore gloves and washed her hands before and after examining the cat. Transmission of cat sneezing is currently hypothetical because the exposure is brief and not very intimate. Relatively low RT-PCR cycle thresholds in nasal swabs obtained from cats (editor's note: Ct values, lower Ct values indicate higher viral loads) indicating high viral loads and contagiousness. Since Patient A was wearing an N95 mask and no face shield or goggles, her exposed ocular surface was susceptible to droplets from cat sneezes. Her infection means the new coronavirus can be transmitted through eye contact, suggesting the importance of wearing protective goggles or face coverings when interacting with high-risk people or animals in close proximity.

The researchers say their study proves that cats can transmit SARS-CoV-2 to humans. However, this incidence of transmission is relatively uncommon because cats shed live virus for a short duration (median 5 days). However, to prevent human-to-cat transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should avoid contact with cats. During close interactions with cats suspected of being infected, caregivers are advised to use eye protection as part of standard personal protection.

Further reading: The host diversity of the new coronavirus

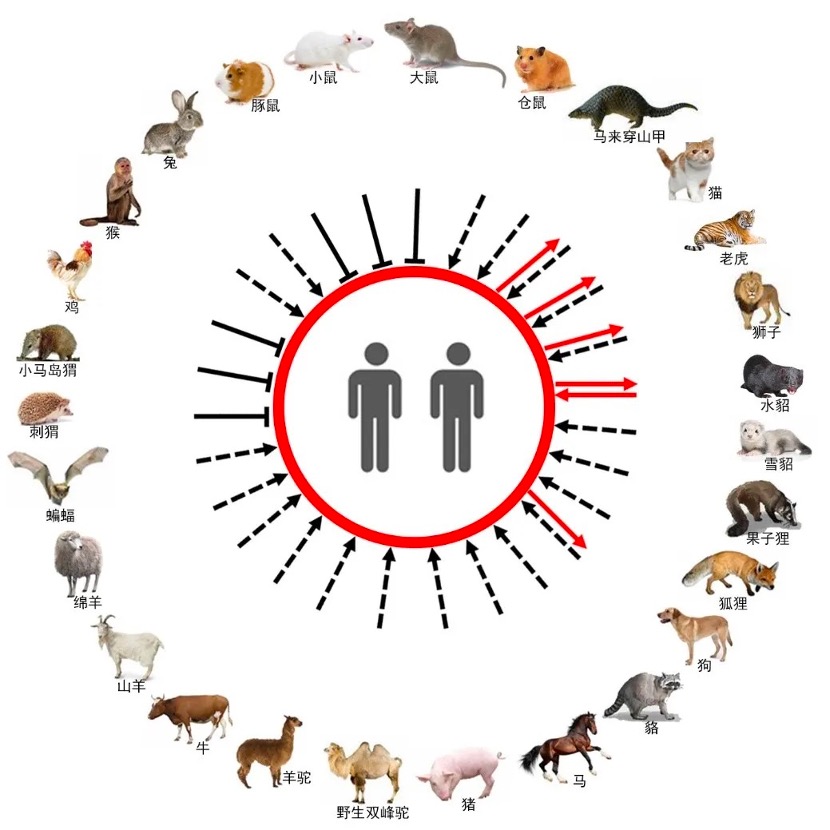

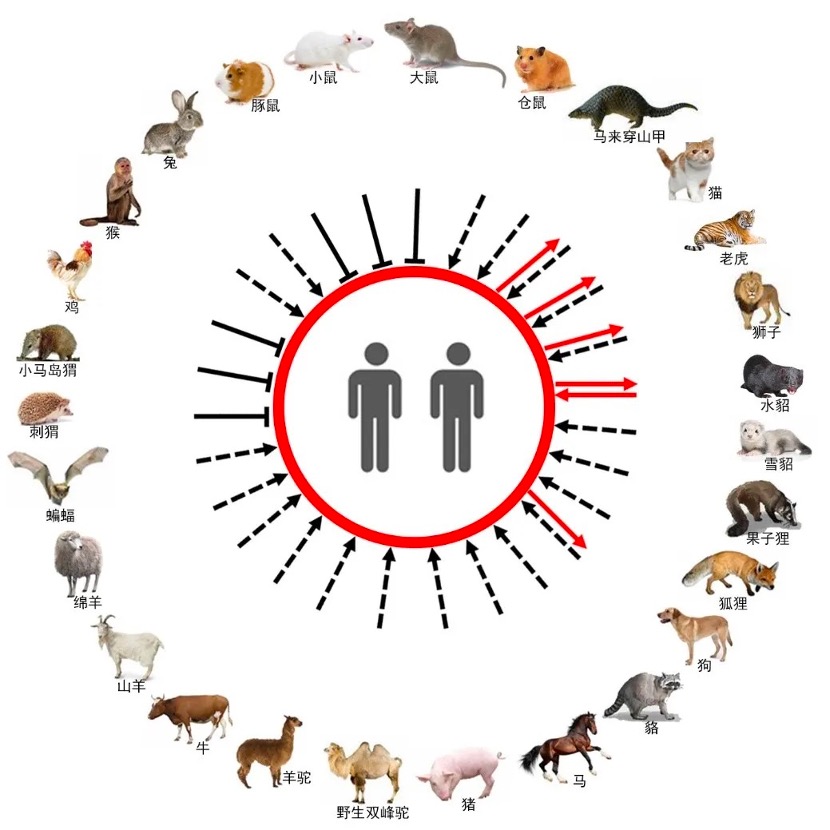

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus that has been found to infect humans. Like SARS-CoV, it uses ACE2 as an invasion receptor. Among them, the interaction between viral envelope proteins and host cell receptors is the first step in mediating viral infection, and also determines the host range of the virus to a large extent.

According to the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the research team took ACE2 from 11 orders and 26 species from Mammalia and Avian as research objects, including domestic animals, pets and wild animals, to explore its relationship with SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) Protein receptor binding domain (RBD) binding.

According to the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the research team took ACE2 from 11 orders and 26 species from Mammalia and Avian as research objects, including domestic animals, pets and wild animals, to explore its relationship with SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) Protein receptor binding domain (RBD) binding.

The results show that SARS-CoV-2 RBD can interact with ACE2 in multiple species (17/26), including primates (monkeys), lagomorphs (rabbits), lepidoptera (Malay pangolins), carnivores (cats) , civet cats, foxes, dogs, raccoon dogs), Oddhoof (horses), Artiodactyla (pigs, wild Bactrian camels, alpacas, cattle, goats, sheep) and Chiroptera (little brown bats, brown fruit bats) , and ACE2 of these species can mediate the entry of SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus into cells.

At the same time, the study also found that SARS-CoV RBD can bind to mouse (rodent) ACE2 in addition to the above 17 species ACE2, which indicates that the host receptor range of SARS-CoV may be different from that of SARS-CoV-2.

This study also ruled out some potential intermediate hosts for SARS-CoV-2, including rodents (guinea pigs, rats, mice), Chiroptera (Chrysanthemum bats, Chrysanthemum bats, Chrysanthemum bats), Insectivores (Western European hedgehog), Afrotheria (Ponytail hedgehog), and Galliformes (chicken).

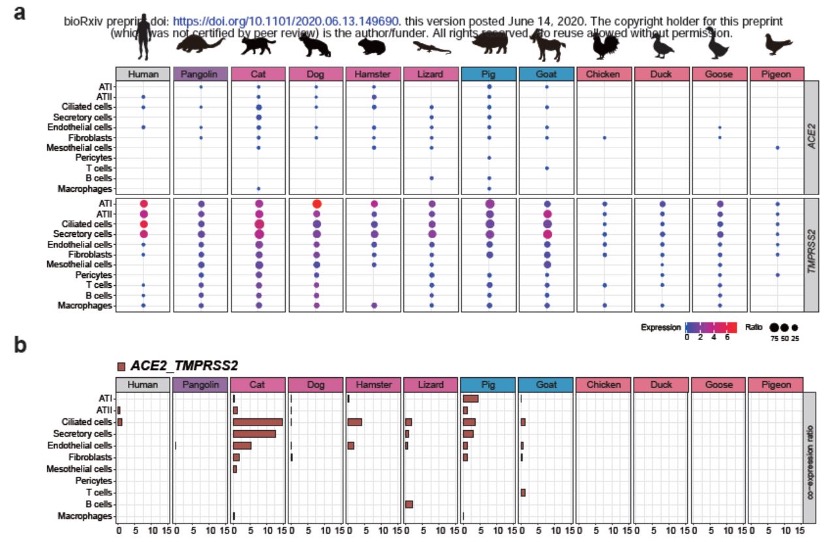

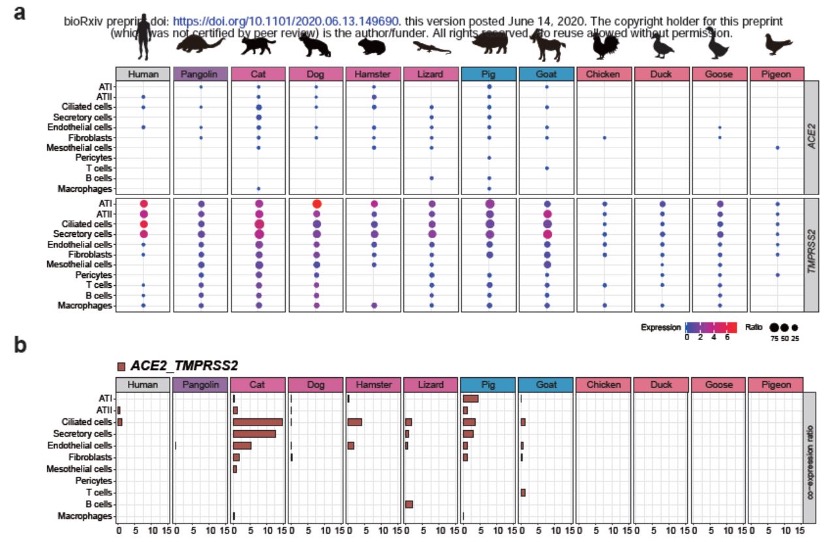

Entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells is also initiated by cleavage of the S protein by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2).

Previously, Chinese researchers created high-quality and comprehensive single-cell maps of the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, large intestine and other tissues of pangolins, cats, and domestic pigs, which are three types of new crown-susceptible animals. The researchers detected ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expressing cells in the cat's lungs, eyelids, esophagus (immune cells) and rectum (intestinal cells). Notably, the researchers found that more than 40% of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expression occurred in cat kidney proximal tubule cells, and about 30% co-expression occurred in cat eyelid epithelial cells.

The researchers detected ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expressing cells in the cat's lungs, eyelids, esophagus (immune cells) and rectum (intestinal cells). Notably, the researchers found that more than 40% of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expression occurred in cat kidney proximal tubule cells, and about 30% co-expression occurred in cat eyelid epithelial cells.

In pangolins, the researchers found that SARS-CoV-2 target cells were present in lung endothelial cells, kidneys (endothelial cells, podocytes and proximal tubule cells), liver (hepatocytes) and spleen (immune cells). In pigs, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are mainly co-expressed in the lung and kidney.

Notably, the researchers showed that, overall, the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 target cells in cats was much higher than the proportions of corresponding cell types in pangolins and pigs.

The lung is one of the main target organs attacked by the new coronavirus, and pneumonia is also a typical symptom of the new coronavirus infection. To assess the detailed expression patterns of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in lung cells of various species, the researchers further generated livestock (pigs, goats), poultry (chickens, pigeons, geese, ducks), pets (cats, dogs, hamsters, lizards) , the monocyte pool of wild animals (pangolins), a total of 123,445 cells were obtained.

The researchers showed that, consistent with previous reports, SARS-CoV-2 replicated poorly in chickens and ducks, and no SARS-CoV-2 target cells were found in the lung cells of poultry (chickens, ducks, geese, and pigeons).

In pigs, co-expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 was observed in 7 of 11 cell types.

In pangolins, the researchers found that a small subset of endothelial cells co-expressed ACE2 and TMPRSS2.

In hamsters, ciliated cells are the most numerous cell type targeted by SARS-CoV-2.

Through epidemiological investigations and viral genome sequencing, the study concluded that a 32-year-old healthy female veterinarian in Thailand was infected with the new coronavirus by a cat. The cat was infected with the new crown by its owner. The corresponding authors of the study are from the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, and the Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

Through epidemiological investigations and viral genome sequencing, the study concluded that a 32-year-old healthy female veterinarian in Thailand was infected with the new coronavirus by a cat. The cat was infected with the new crown by its owner. The corresponding authors of the study are from the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, and the Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.Between July and September 2021, the COVID-19 outbreak in Thailand is shifting from an alpha variant to a delta variant. On August 15, 2021, a 32-year-old healthy female veterinarian, Patient A, visited the Prince of Songkhla University Hospital in Hat Yai District, Songkhla Province, in the prosperous Songkhla Province in southern Thailand.

Patient A, living alone in a dormitory on campus, sought medical attention because of fever, runny nose, and a productive cough that lasted for 2 days. Physical examination was acceptable, but chest X-ray showed unremarkable findings. When asked about her medical history, she stated that 5 days ago, she and 2 other veterinarians (E and F) examined a cat. This cat was owned by a father and son duo (patients B and C).

Patient B, 32, and Patient C, 64, live in Bangkok, the capital of Thailand. On August 7, they tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid, but because there was no hospital bed in Bangkok, the father and son were transferred to the Prince of Songkhla University Hospital. On August 8, 2021, patients B and C were transported by ambulance along with their cats, a 20-hour drive, a distance of 900 km.

Timeline of suspected cat-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Thailand, August 2021.

Upon arriving at the Prince of Songkla University School of Medicine, the father and son and the cat were immediately admitted to the isolation ward. On August 10, 2021, the cat, who slept in the same bed as the patient, was taken to the University Veterinary Hospital for examination by Patient A, who was found to be clinically normal. Patient A collected nasal and anal swab samples from the cat, while two other veterinary patients, E and F, were responsible for the control of the cat. While taking the nasal swab, the cat sneezed into Patient A's face. At the time, all 3 veterinarians were wearing disposable gloves and N95 masks, but none were wearing face shields or goggles. The contact time of the entire veterinary team with the cats lasted about 10 minutes.Patient A developed symptoms 3 days after being in contact with the cat, but did not seek medical advice until the cat's nucleic acid test came back positive on August 15. After investigation, patient A's nasopharyngeal swab tested positive for the new crown. Patients A, B and C and the cat were taken to hospital for isolation. Nasopharyngeal swabs from E and F were negative.

None of the close contacts of patient A were tested positive for the new coronavirus. A contact tracing investigation of all 30 staff working at the veterinary hospital found that 1 other veterinarian (patient G) had been in contact with other COVID-19 patients, working in the large animal department. Patient G developed a fever 1 day before the cat's arrival and tested positive for 2019-nCoV on August 13, 2021. Patient G reported no direct or indirect contact with cats or patients A, E, or F.

The researchers further sequenced the new coronaviruses of patient G and patients A, B, C, and cats. The researchers also tested SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA from other Songkhla patients before genotyping. By visualizing the phylogenetic tree, the researchers found that the genomes of patients B, C, and cats were the same as those of patient A, but they were different from those of other patients in the same province.

As shown below:

The same SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence obtained from patient A and sequences obtained from the cat and its 2 owners, as well as the temporal overlap of animal and human infections, suggest that this series of infections is epidemiologically, according to the investigators. is relevant. Since patient A had not met patient B or C before, when the cat sneezed, she may have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 by the cat. The genome sequence was different from that of patient G and other sequences circulating in the same province, and by using the pairwise distance formula, the researchers ruled out the possibility of external transmission. The alpha variant spread widely in Songkhla until the end of July 2021; but in Bangkok, the delta variant has been very common since early July 2021.

The same SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence obtained from patient A and sequences obtained from the cat and its 2 owners, as well as the temporal overlap of animal and human infections, suggest that this series of infections is epidemiologically, according to the investigators. is relevant. Since patient A had not met patient B or C before, when the cat sneezed, she may have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 by the cat. The genome sequence was different from that of patient G and other sequences circulating in the same province, and by using the pairwise distance formula, the researchers ruled out the possibility of external transmission. The alpha variant spread widely in Songkhla until the end of July 2021; but in Bangkok, the delta variant has been very common since early July 2021.The researchers suggest that the chain of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the cluster likely started in Bangkok. Cats are known to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially during close interactions with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2-infected humans. Because of the relatively short incubation and infectious periods of an infected cat, this cat may have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 less than a week before it could potentially transmit the disease to Patient A.

While direct or indirect (contaminant) contacts are also potential routes of transmission to Patient A, these are less likely. The researchers analyzed because she wore gloves and washed her hands before and after examining the cat. Transmission of cat sneezing is currently hypothetical because the exposure is brief and not very intimate. Relatively low RT-PCR cycle thresholds in nasal swabs obtained from cats (editor's note: Ct values, lower Ct values indicate higher viral loads) indicating high viral loads and contagiousness. Since Patient A was wearing an N95 mask and no face shield or goggles, her exposed ocular surface was susceptible to droplets from cat sneezes. Her infection means the new coronavirus can be transmitted through eye contact, suggesting the importance of wearing protective goggles or face coverings when interacting with high-risk people or animals in close proximity.

The researchers say their study proves that cats can transmit SARS-CoV-2 to humans. However, this incidence of transmission is relatively uncommon because cats shed live virus for a short duration (median 5 days). However, to prevent human-to-cat transmission of SARS-CoV-2, patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should avoid contact with cats. During close interactions with cats suspected of being infected, caregivers are advised to use eye protection as part of standard personal protection.

Further reading: The host diversity of the new coronavirus

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus that has been found to infect humans. Like SARS-CoV, it uses ACE2 as an invasion receptor. Among them, the interaction between viral envelope proteins and host cell receptors is the first step in mediating viral infection, and also determines the host range of the virus to a large extent.

According to the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the research team took ACE2 from 11 orders and 26 species from Mammalia and Avian as research objects, including domestic animals, pets and wild animals, to explore its relationship with SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) Protein receptor binding domain (RBD) binding.

According to the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the research team took ACE2 from 11 orders and 26 species from Mammalia and Avian as research objects, including domestic animals, pets and wild animals, to explore its relationship with SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) Protein receptor binding domain (RBD) binding.The results show that SARS-CoV-2 RBD can interact with ACE2 in multiple species (17/26), including primates (monkeys), lagomorphs (rabbits), lepidoptera (Malay pangolins), carnivores (cats) , civet cats, foxes, dogs, raccoon dogs), Oddhoof (horses), Artiodactyla (pigs, wild Bactrian camels, alpacas, cattle, goats, sheep) and Chiroptera (little brown bats, brown fruit bats) , and ACE2 of these species can mediate the entry of SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus into cells.

At the same time, the study also found that SARS-CoV RBD can bind to mouse (rodent) ACE2 in addition to the above 17 species ACE2, which indicates that the host receptor range of SARS-CoV may be different from that of SARS-CoV-2.

This study also ruled out some potential intermediate hosts for SARS-CoV-2, including rodents (guinea pigs, rats, mice), Chiroptera (Chrysanthemum bats, Chrysanthemum bats, Chrysanthemum bats), Insectivores (Western European hedgehog), Afrotheria (Ponytail hedgehog), and Galliformes (chicken).

Entry of SARS-CoV-2 into host cells is also initiated by cleavage of the S protein by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2).

Previously, Chinese researchers created high-quality and comprehensive single-cell maps of the heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, large intestine and other tissues of pangolins, cats, and domestic pigs, which are three types of new crown-susceptible animals.

The researchers detected ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expressing cells in the cat's lungs, eyelids, esophagus (immune cells) and rectum (intestinal cells). Notably, the researchers found that more than 40% of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expression occurred in cat kidney proximal tubule cells, and about 30% co-expression occurred in cat eyelid epithelial cells.

The researchers detected ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expressing cells in the cat's lungs, eyelids, esophagus (immune cells) and rectum (intestinal cells). Notably, the researchers found that more than 40% of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 co-expression occurred in cat kidney proximal tubule cells, and about 30% co-expression occurred in cat eyelid epithelial cells.In pangolins, the researchers found that SARS-CoV-2 target cells were present in lung endothelial cells, kidneys (endothelial cells, podocytes and proximal tubule cells), liver (hepatocytes) and spleen (immune cells). In pigs, ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are mainly co-expressed in the lung and kidney.

Notably, the researchers showed that, overall, the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 target cells in cats was much higher than the proportions of corresponding cell types in pangolins and pigs.

The lung is one of the main target organs attacked by the new coronavirus, and pneumonia is also a typical symptom of the new coronavirus infection. To assess the detailed expression patterns of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in lung cells of various species, the researchers further generated livestock (pigs, goats), poultry (chickens, pigeons, geese, ducks), pets (cats, dogs, hamsters, lizards) , the monocyte pool of wild animals (pangolins), a total of 123,445 cells were obtained.

The researchers showed that, consistent with previous reports, SARS-CoV-2 replicated poorly in chickens and ducks, and no SARS-CoV-2 target cells were found in the lung cells of poultry (chickens, ducks, geese, and pigeons).

No SARS-CoV-2 target cells were found in lung cells of poultry (chickens, ducks, geese, and pigeons).

SARS-CoV-2 target cells were detected in eight of the 11 cell types in cats investigated by the researchers, and the two cells with the most 2019-nCoV target cells were ciliated and secretory cells.In pigs, co-expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 was observed in 7 of 11 cell types.

In pangolins, the researchers found that a small subset of endothelial cells co-expressed ACE2 and TMPRSS2.

In hamsters, ciliated cells are the most numerous cell type targeted by SARS-CoV-2.

Comments