Global cases of unexplained childhood hepatitis are still on the rise. The latest data comes from Japan, which added 11 cases as of last week, bringing the total to 47. Globally, 34 countries have reported about 700 cases of unexplained childhood hepatitis, with 112 suspected cases, at least 38 undergoing liver transplants, and 10 deaths, according to a summary by the World Health Organization (WHO). Most children present with early gastrointestinal symptoms, which later develop jaundice and, in some cases, acute liver failure. To the confusion of scientists, the hepatitis A, B, C, D and E viruses were not found in these children.

Previously, the UK Health Safety Agency listed adenovirus as the first hypothesis of acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children, but this claim has been increasingly questioned. At present, academic and clinical analysis believe that the new coronavirus plays a role that cannot be ignored. It is worth noting that the International Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology "JPGN" published a study of unexplained childhood hepatitis from Israel. After a thorough examination of the disease, other known causes were excluded. The classification of pediatric cases with histopathological and histopathological features suggested two distinct patterns of 'coronavirus' hepatitis manifestations in children.

The study, titled "Long COVID-19 Liver Manifestation in Children," was published on June 10, and the research team included the Institute of Nutrition and Liver Diseases, Israel Metabolic Disease Clinic, Schneider Children's Medical Center, and the Department of Pathology at Rabin Medical Center , Rambam Medical Center Institute of Gastroenterology, Tel Aviv University, etc.

The study reports on five Israeli children who recovered from Covid-19 infection but subsequently developed severe liver damage. The researchers divided it into two types of clinically manifested "long-term new coronary" hepatitis: acute liver failure and hepatitis with cholestasis. The five children with severe hepatitis of unknown cause were all from Schneider Children's Medical Center in Israel in 2021.

The first type of "long-term new crown" hepatitis reported by the researchers occurred in two infants aged 3 and 5 months. They were previously healthy but rapidly developed acute liver failure requiring liver transplantation. Their livers showed massive necrosis with bile duct proliferation and lymphocytic infiltration.

Type II hepatitis with cholestasis occurred in 3 children (two 8 years old and one 13 years old). The investigators performed liver biopsies in 2 of the children, where lymphocyte hilum and parenchymal inflammation and bile duct proliferation were prominent. All three were treated with steroids, and liver enzymes improved and they were able to end treatment.

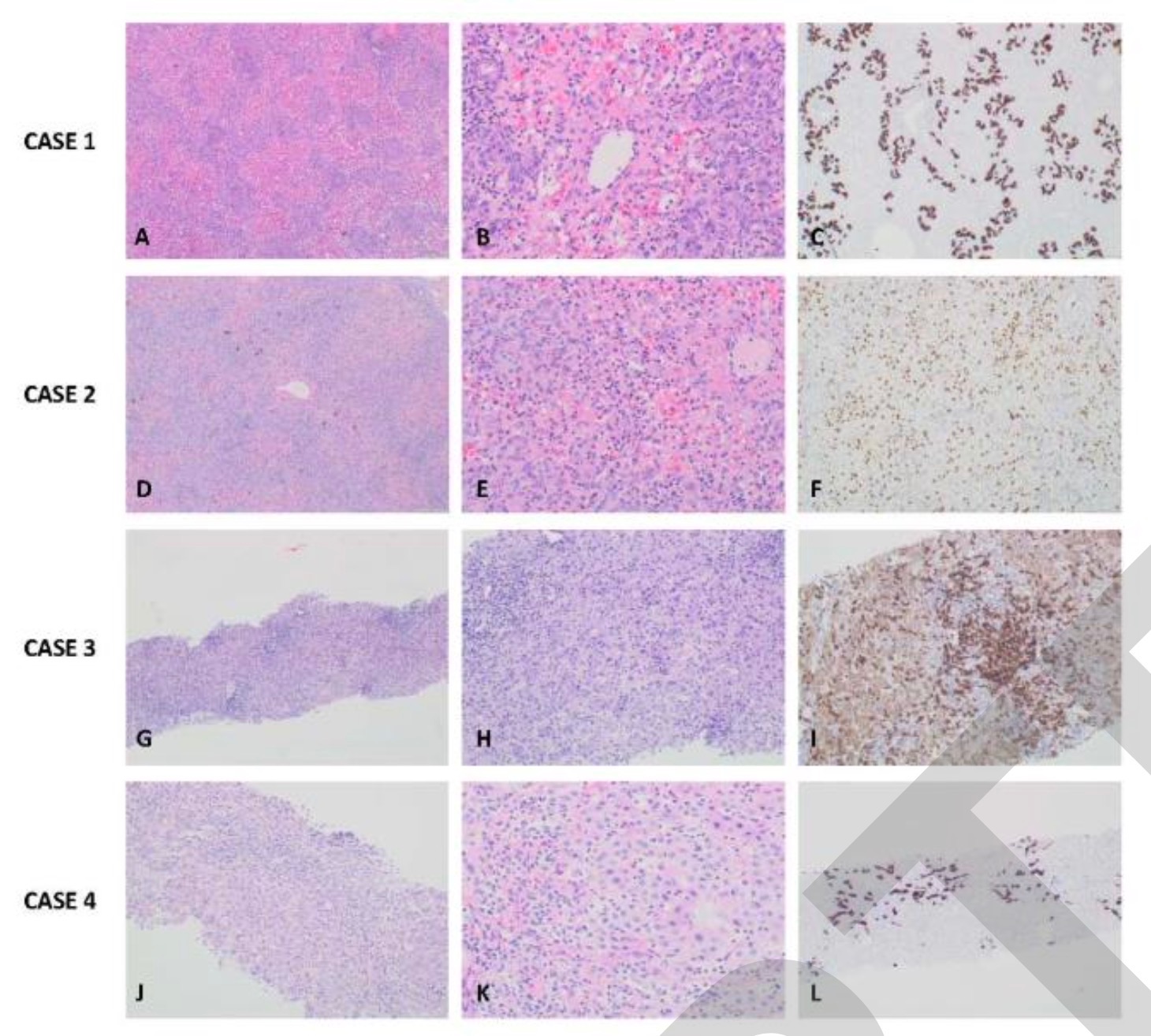

Notably, the investigators performed extensive etiological testing for infectious and metabolic etiologies in all five patients, which were negative, excluding other known causes.

Previously, the global clinical medical community has reported numerous cases of liver injury during acute infection of the new coronavirus; cases of bile duct inflammation after recovery from the infection of the new coronavirus have also been reported in adults. Among the 5 cases reported in Israel, the average onset time was 74.5 days (range 21-130 days) after the positive for the new coronavirus nucleic acid.

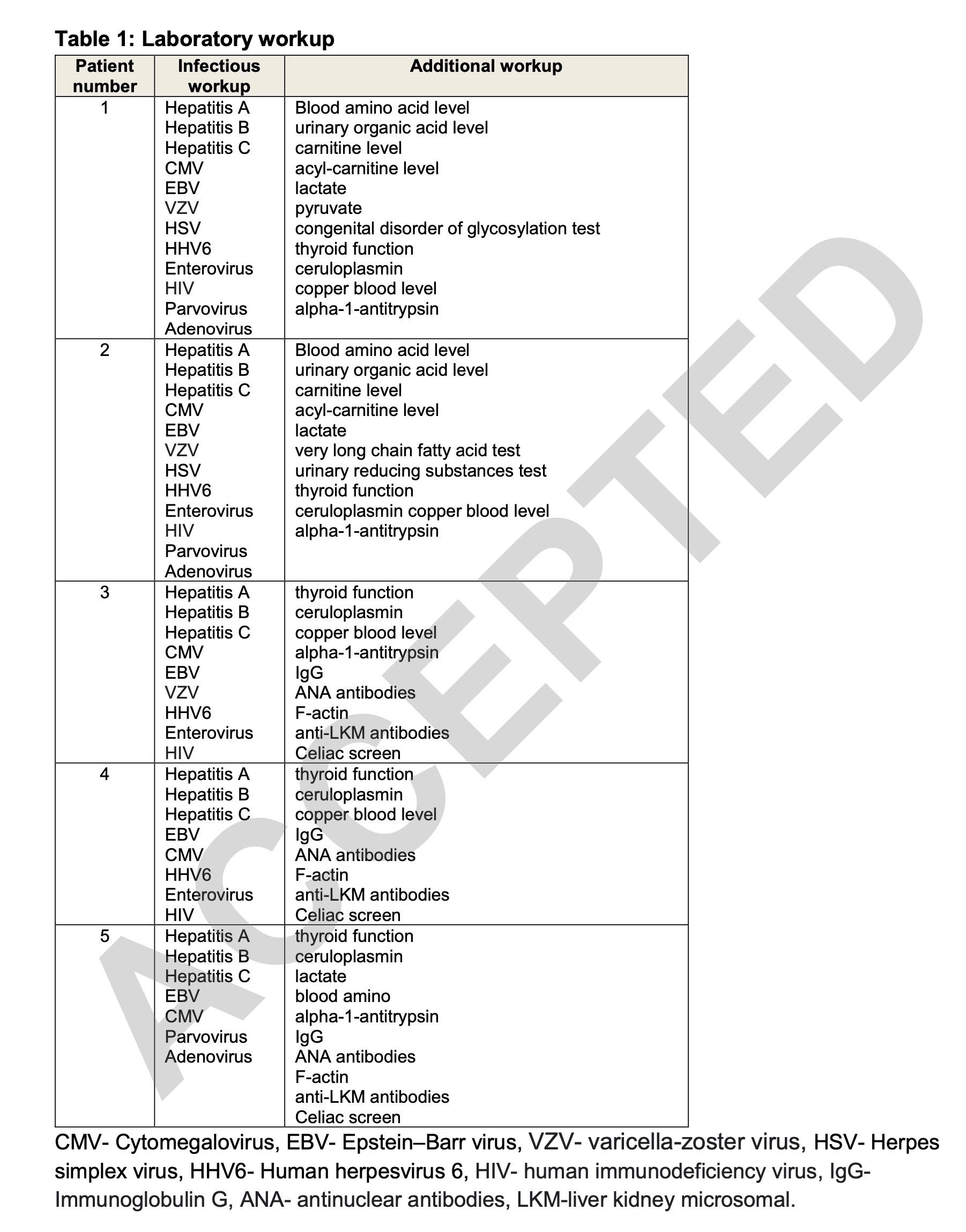

The imaging features of these 5 cases of "long-term COVID-19" hepatitis in Israel included increased periportal echogenicity, biliary dilatation, ductal, portal edema, and gallbladder wall thickening. Their histological features included ductal reaction, portal and sinus congestion, and portal and parenchymal lymphocytic infiltration. In terms of treatment, systemic corticosteroid therapy may be beneficial in similar patients.

Patient 1 is a 3-month-old infant who developed fever in February 2021 and was tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by nucleic acid.

He was born at 36 weeks gestation with a birth weight as low as 2300 grams, otherwise he is healthy and able to grow and develop normally. After being diagnosed with the new crown, he will not receive any treatment and will not need to be hospitalized.

But on the 21st day after the new crown diagnosis, he came to the hospital emergency room with 4 days of progressive jaundice. On arrival at the hospital, his temperature and vital signs were normal, and the physical examination was only significant for jaundice.

Laboratory test his AST (aspartate aminotransferase) up to 2078IU/L, ALT (alanine aminotransferase) up to 1440IU/L, GGT (glutamyl transferase) up to 63IU/L, ALP (alkaline phosphatase) Up to 2042IU/L, total bilirubin 18.5mg/dL, direct bilirubin 14.5mg/dL, albumin 4g/dL, ammonia 184mcg/dL, INR 5.5. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

Due to coagulopathy in patient 1, vitamin K was given, but the situation did not improve. He was taken to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of acute liver failure. Laboratory tests for infectious and metabolic causes were negative (Table 1). IgG antibody to SARS-CoV-2 was positive (3474AU/ml).

Genetically, a whole exome analysis was performed on patient 1 and his parents. In addition, regions associated with the acute liver failure phenotype, including NBAS and SCYL1 variants, were analyzed. Two compound heterozygous missense variants were detected in the gene MAN2B2 - c.112G>A;p.Asp38Asn and c.1211T>C;p.Leu404pro. Previous studies have shown that this variant of the gene is also present in patients without liver disease. Because these specific variants were not described in patients with liver failure in the literature or local databases in Israel, they were classified as variants of uncertain significance with low disease-causing potential.

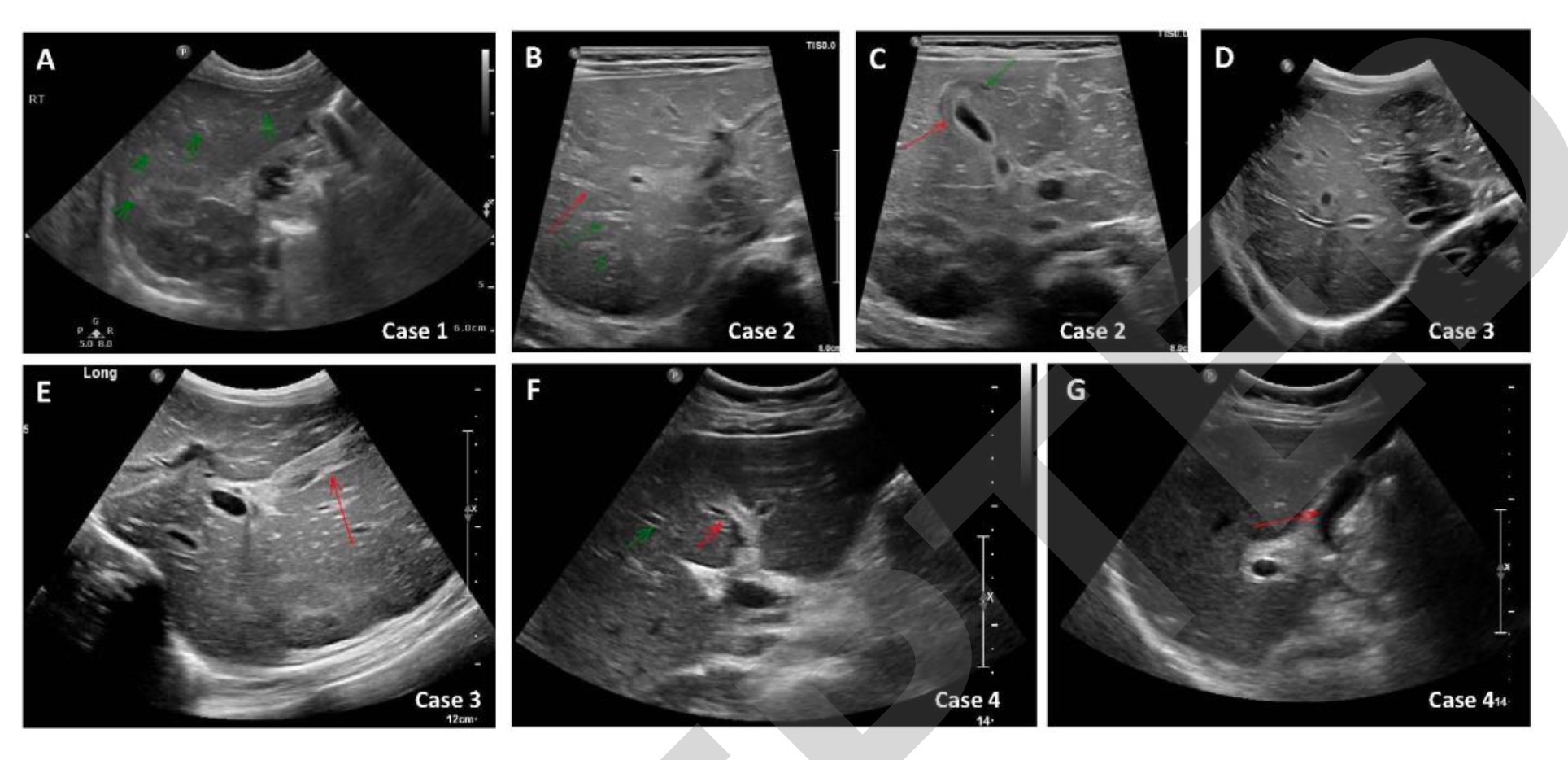

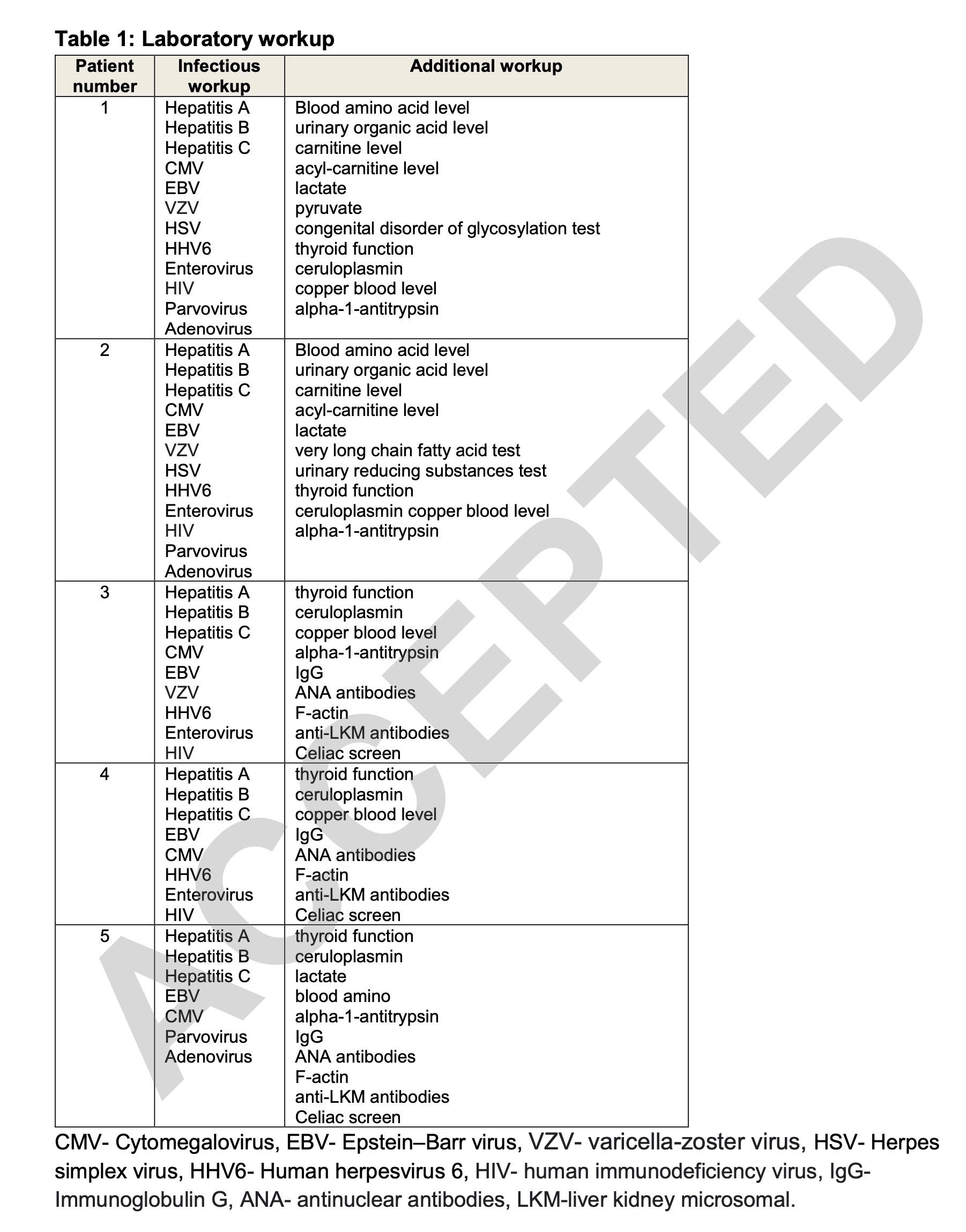

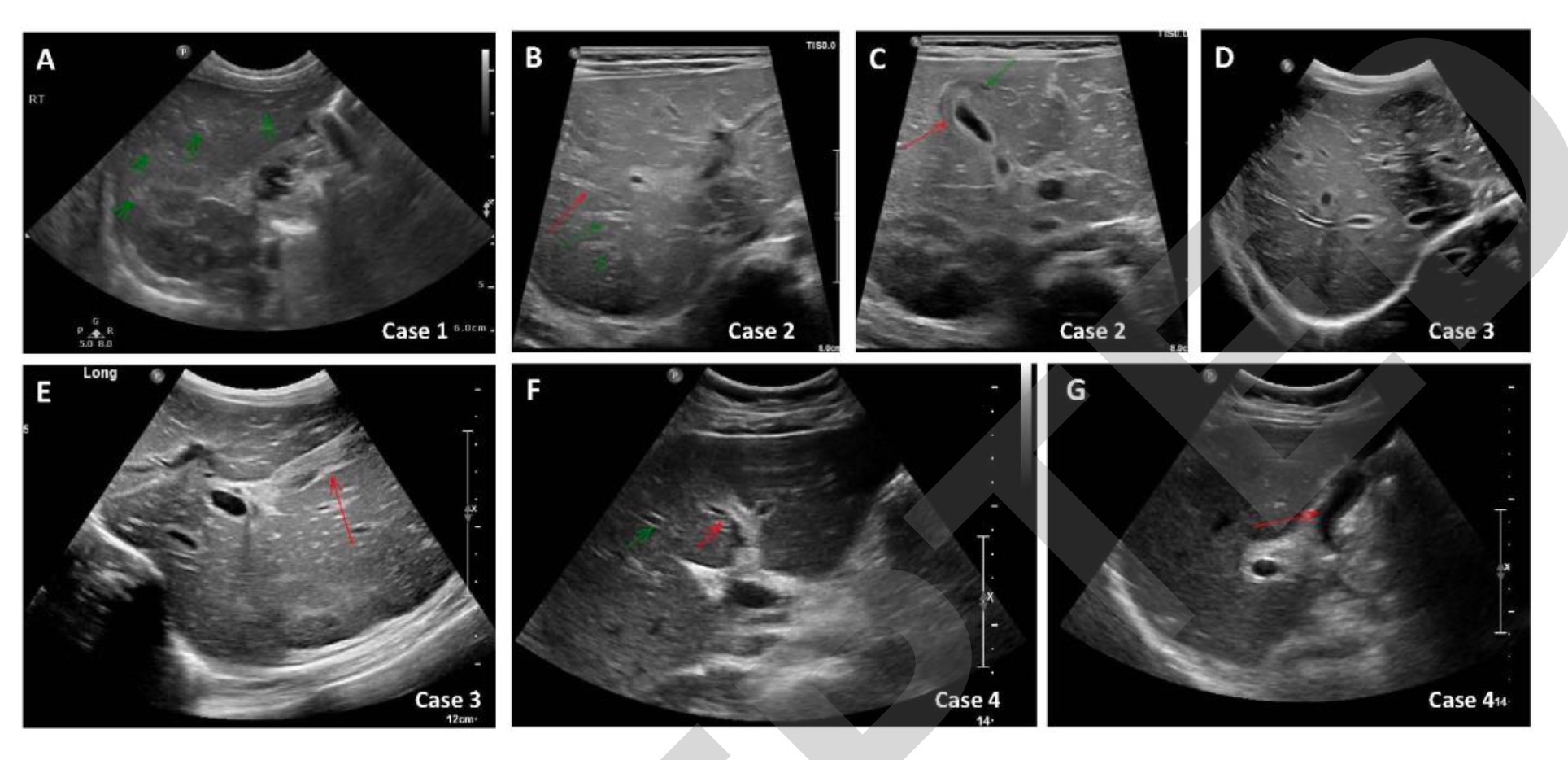

Abdominal ultrasonography of patient 1 showed an increase in periportal echogenicity that was otherwise inconspicuous (Fig. 1A). As the synthetic function of the liver continued to deteriorate, he developed encephalopathy and required a liver transplant. Patient 1 underwent a living donor left liver transplant from his father on day 32 due to further deterioration of his condition. Histological examination of the liver of patient 1 showed pericentral and panlobular necrosis, prominent bile duct hyperplasia, and lymphocytic infiltration in the portal venous region and parenchyma. Staining was negative for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2A-C). The patient recovered well and continued with outpatient follow-up at the liver transplant clinic.

Patient 2 is a 5-month-old baby. In May 2021, he came to the emergency room with 2 days of jaundice, dark urine, and biliary soft stools. At that time, it was judged that no drug treatment was needed. Ten days before admission, he had worsening reflux and refusal to eat, and was started on Gaviscon (a stomach drug) for several days, followed by an anti-reflux formula, and his symptoms subsided.

Upon arrival at the hospital, Patient 2 had a fever to 38.0°C and normal vital signs. Physical examination was marked by jaundice and hepatomegaly. Laboratory tests are AST up to 2265IU/L, ALT up to 2219IU/L, GGT up to 124IU/L, ALP up to 1034IU/L, total bilirubin 7.7mg/dL, direct bilirubin 4.5mg/dL, albumin 4.3g /dL, ammonia 110 μg/dL. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

Patient 2's INR after vitamin K administration was 1.85. Patient 2 was taken to the intensive care unit for further examination. During admission, he developed secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) with cytopenias, high ferritin levels, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated IL-2 levels, and phagocytosis on liver histology. blood cells.

As part of the Primary Immunodeficiency Panel, we performed gene sequence analysis and deletion/duplication testing on 407 genes in Patient 2 due to HLH. Testing included NBAS variants, and results included a variant in NOD2, a gene known as risk for Crohn's disease, and variants of uncertain clinical significance in three gene factors, CIITA, DOCK8 and WDR1.

Patient 2 was listed as requiring liver transplantation because his INR continued to rise. On day 7 after admission, he had clinical deterioration with encephalopathy and subsequently received a living donor liver transplant from his mother (left segment).

Laboratory tests for infectious and metabolic causes of patient 2 revealed positive PCR for adenovirus in his whole blood (Table 1). IgG antibody to SARS-CoV-2 was positive (2629AU/ml). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed hepatomegaly, bile duct dilatation, periportal edema, and gallbladder wall thickening (Figures 1B and 1C).

Histological examination of the liver of patient 2 showed extensive panlobular necrosis, mainly pericentric necrosis, marked bile duct hyperplasia, and canalicular cholestasis. Hepatic sinusoids have extensive mononuclear cell infiltration and hemophagocytic signs. Staining was negative for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2D-F). Postoperatively, Child 2 was PCR positive for cytomegalovirus and adenovirus and received ganciclovir and cidofovir. Hepatic liver disease resolves spontaneously without specific treatment. Liver staining was negative for three viruses that may cause secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (ie, CMV, adenovirus, and COVID-19).

Acute hepatitis with cholestasis

Patient 3 was an 8-year-old boy who was previously healthy. When his mother tested positive for the new coronavirus nucleic acid, he was also tested and found that he was also infected, but the symptoms were very mild, and he did not receive any treatment and was not admitted to the hospital.

On the 130th day after patient 3 was diagnosed with Covid-19, he was admitted to the emergency room with abdominal pain and vomiting for a week and jaundice for two days. He was afebrile, his vital signs were normal, and his physical examination revealed jaundice with hepatomegaly.

Laboratory testing on patient 3 showed that his AST was as high as 3598IU/L, ALT was as high as 3561IU/L, GGT was as high as 167IU/L, ALP was as high as 496IU/L, total bilirubin 8.1mg/dL, direct bilirubin 5.1mg /dL, albumin 4.2 g/dL and ammonia 50 mcg/dL. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

After vitamin K administration to patient 3, his INR was 1.5. Laboratory tests for infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic causes were negative (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed mild hepatomegaly, bile duct protrusion, and gallbladder wall edema (Figures 1D and 1E). On day 4 of admission, patient 3 underwent a liver biopsy. Histological examination was characterized by portal and sinusoidal congestion, bile duct hyperplasia, and marked lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltration in the portal space and lobules.

Patient 3 stained negative for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV, and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2G-I).

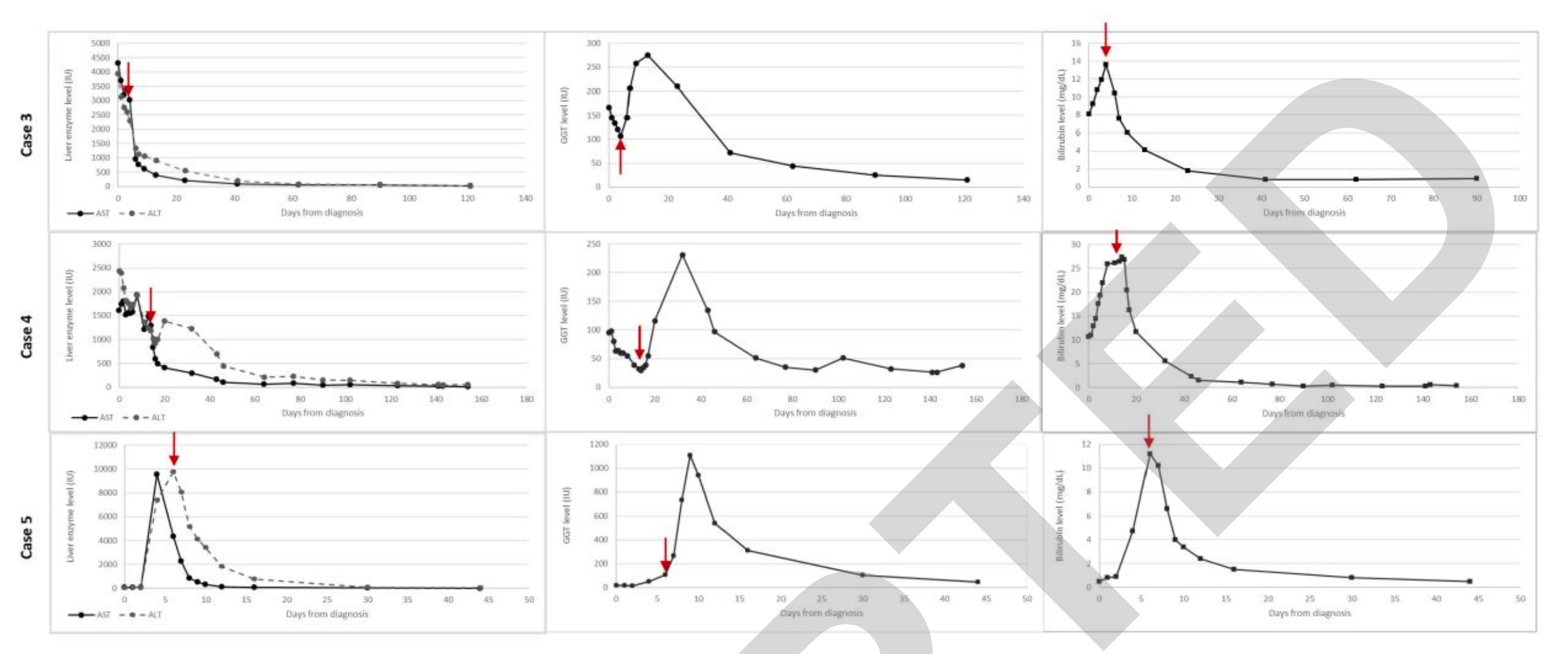

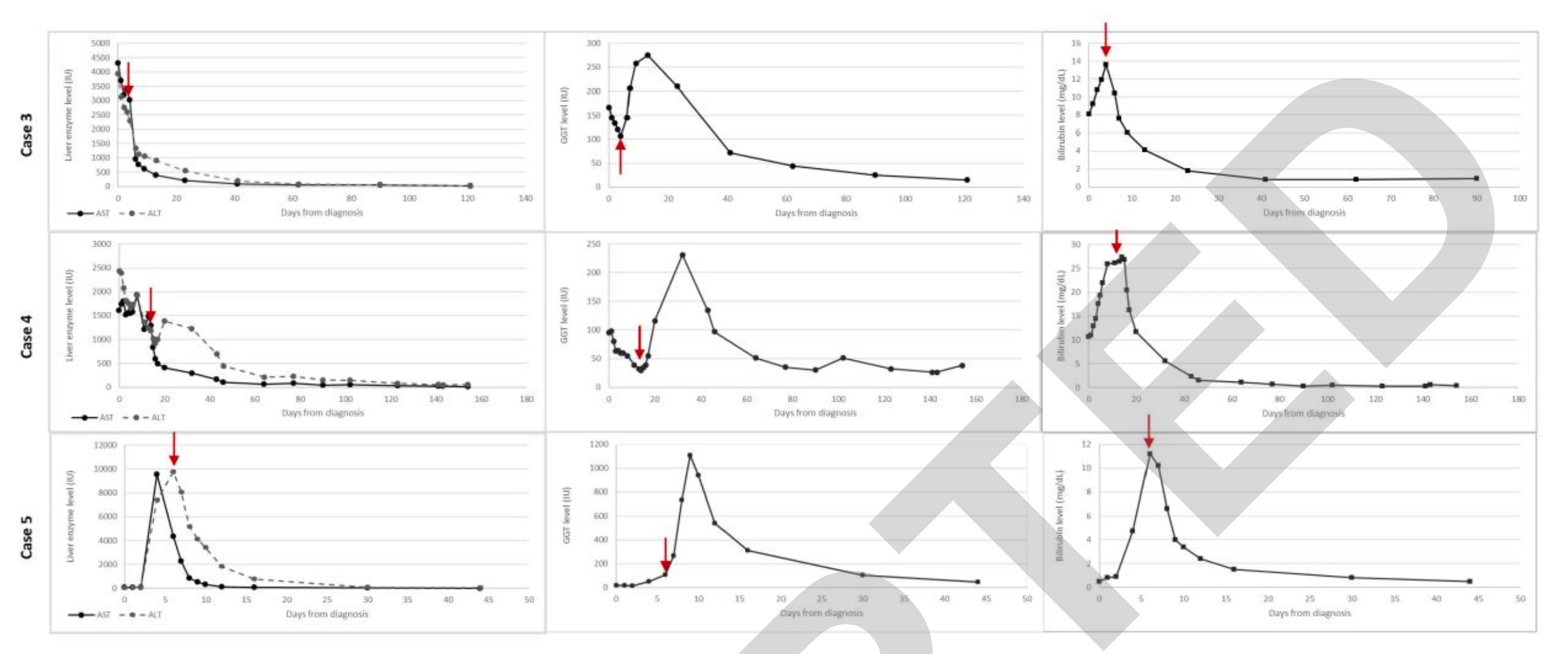

Patient 3 then began to receive methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day injection therapy. Its hepatocytes and cholestatic enzymes, INR were rapidly improved. He was subsequently switched to oral prednisolone and then gradually discontinued over 4 months (Figure 3). His liver enzymes fully returned to normal after 4 months and have remained normal ever since.

Patient 4 was an 8-year-old boy who had fever and cough in January 2021 and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid. He received no treatment and was not admitted to hospital.

His body mass index BMI was above 97% for his age, and he was known to have mildly elevated AST and ALT (79 IU/L and 47 IU/l, respectively), which was thought to be secondary to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease .

On the 94th day after the diagnosis of Covid-19 infection, patient 4 presented to the emergency room with three days of fever to 39°C, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea and jaundice. His temperature and vital signs were normal, and physical examination revealed hepatomegaly and jaundice.

Laboratory tests of patient 4 were AST up to 1551IU/L, ALT up to 2439IU/L, GGT up to 95IU/L, ALP up to 499IU/L, total bilirubin 10.3mg/dL, direct bilirubin 6.2mg/dL, white blood Protein 4.2g/dL, ammonia 71mcg/dL, INR1.2. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

The investigators performed laboratory tests for infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic causes in patient 4, which were negative (Table 1) and positive for IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (376 AU/ml). Abdominal ultrasound showed bile duct dilatation and gallbladder wall thickening (Figures 1F and 1G). A liver biopsy 13 days after admission revealed portal and sinus congestion, dilation and proliferation of bile duct margins, and prominent lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltration in the portal space and lobules.

The investigators stained patient 4 liver biopsy sections for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV, and SARS-CoV-2, all of which were negative (Figure 2J-L). Two days after the liver biopsy, patient 4 was started on systemic steroids. ALT, AST, GGT, bilirubin, and ALP levels gradually decreased and returned to normal after 4 months, during which time the steroid medication was gradually discontinued (Figure 3). Two months after his visit, he was diagnosed with aplastic anemia. Targeted next-generation sequencing and analysis of the bone marrow failure gene panel was negative. He underwent a successful bone marrow transplant in September 2021 and is in good health.

Patient 5 was a previously healthy 13-year-old boy. In September 2021, he presented with 5 days of weakness, diarrhea and abdominal pain, and his temperature and vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed jaundice. Laboratory tests on patient 5 showed AST up to 2901IU/L, ALT up to 9376IU/L, GGT up to 141IU/L, ALP up to 396IU/L, total bilirubin 12mg/dL, direct bilirubin 8.8mg/dL, Albumin 3.8g/dL, ammonia 62mcg/dL and INR 1.2. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

Patient 5 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid and was hospitalized for observation, after which there was gradual clinical and laboratory improvement without medication, and his liver enzymes returned to normal 39 days after infection.

On day 53 of the COVID-19 diagnosis, patient 5 came to the emergency room with another 10 days of vomiting and abdominal pain. His fever and vital signs were normal. On physical examination, jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness were present. Laboratory tests were AST up to 8501IU/L, ALT up to 10560IU/L, GGT up to 66IU/L, ALP up to 445IU/L, total bilirubin 10.4mg/dL, direct bilirubin 6.6mg/dL, albumin 3.6g /dL and ammonia 214mcg/dL.

Laboratory tests for infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic causes were negative for patient 5 (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasonography was normal. On the day of admission, the patient was started on systemic steroids. ALT, AST, and ALP levels gradually decreased (Figure 3). Steroid therapy has now ended and his liver enzymes remain normal.

Histological features rule out adenoviral hepatitis

This Israeli study describes the clinical phenotypes of two liver manifestations associated with recent COVID-19 disease: acute liver failure and acute hepatitis with cholestasis. Previous studies have found that severe cholestasis occurs mainly in adults. In the Israeli study, two patients with acute liver failure were infants (3 and 5 months). The 3 patients with acute hepatitis with cholestasis were older (8-13 years).

The five patients were all asymptomatic or mildly ill with the new coronavirus. Their bile duct disease appeared months after the COVID-19 diagnosis. For four patients in Israel (another was transferred), the mean time from COVID-19 diagnosis to cholangiopathic diagnosis was 74.5 days (range 21-130). Patient 5 was found to have been infected with COVID-19 by serological testing, but the exact time of infection was unknown.

Similar to the description in adults, ultrasound studies of four patients in the Israeli study showed bile duct or gallbladder involvement. Specifically, hepatomegaly, bile duct dilatation, periportal edema, or edema and thickening of the gallbladder wall were found to be significant. In adults, ultrasonographic findings are mainly applicable to focal strictures of the intrahepatic bile ducts with intraluminal sludge and casts, consistent with the radiographic features of SSC.

Liver histology from the Israeli study showed some similarities between patients. Biopsy showed statistically significant bile duct hyperplasia, portal and sinus congestion, portal lymphocyte infiltration, eosinophilic infiltration, and hepatic parenchyma inflammatory infiltration. A previous systematic review of histopathological findings on liver biopsies in adults with COVID-19 showed that the most common findings were centrilobular hyperemia and steatosis, which are associated with pre-existing obesity and diabetes. Other findings described in adults include hepatocyte necrosis, mild to moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the periportal area, cholestasis with biliary embolism, ductal reaction, and cholangiocyte nuclear polymorphism.

In contrast to the adult cohort, in the pediatric cohort of this study from Israel, steatosis was absent, the researchers noted. This may imply that the steatosis observed in the adult cohort is related to other comorbidities than to COVID-19.

More recently, severe acute hepatitis has been reported in increasing numbers of children in the UK, EU, US, Israel and Japan. In England and Scotland, 68% and 50% of cases respectively tested positive for adenovirus, mainly in blood. The etiology of the cases is unclear, as adenoviruses usually cause severe hepatitis only in immunocompromised hosts.

Nevertheless, the increased incidence of adenovirus in the described cases prompted the Israeli study to further confirm whether an adenovirus infection might be involved, the researchers said. Previous studies have shown that histological features of adenoviral hepatitis include extensive hepatocyte necrosis, mild inflammation, intranuclear inclusions, and positive immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens in infected hepatocytes. Specimens described by the European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention included six explanted livers and eight biopsies from cases in the UK and Scotland. Adenovirus immunohistochemistry has been reported in 9 out of 14 samples to date, showing immunoreactivity in the hepatic sinusoid lumen but not in hepatocytes. 1 routine liver tissue adenovirus polymerase chain reaction, the result was negative.

They cite another previous study from other laboratories that described liver biopsies from six pediatric patients showing varying degrees of hepatitis, but no viral inclusions were observed, no immunohistochemical evidence for adenovirus, and no pass Electron microscopy to identify virus particles.

Notably, the Israeli study also performed adenovirus immunohistochemical staining in all patients who underwent liver biopsy or liver explantation. Adenovirus staining was negative, and histological features were not suggestive of adenovirus hepatitis. Three patients had adenovirus PCR from whole blood, and one patient was positive. However, since liver histology did not suggest adenovirus infection, the Israeli study did not consider it to be the culprit for unexplained childhood hepatitis.

Previously, the UK Health Safety Agency listed adenovirus as the first hypothesis of acute hepatitis of unknown cause in children, but this claim has been increasingly questioned. At present, academic and clinical analysis believe that the new coronavirus plays a role that cannot be ignored. It is worth noting that the International Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology "JPGN" published a study of unexplained childhood hepatitis from Israel. After a thorough examination of the disease, other known causes were excluded. The classification of pediatric cases with histopathological and histopathological features suggested two distinct patterns of 'coronavirus' hepatitis manifestations in children.

The study, titled "Long COVID-19 Liver Manifestation in Children," was published on June 10, and the research team included the Institute of Nutrition and Liver Diseases, Israel Metabolic Disease Clinic, Schneider Children's Medical Center, and the Department of Pathology at Rabin Medical Center , Rambam Medical Center Institute of Gastroenterology, Tel Aviv University, etc.

The study reports on five Israeli children who recovered from Covid-19 infection but subsequently developed severe liver damage. The researchers divided it into two types of clinically manifested "long-term new coronary" hepatitis: acute liver failure and hepatitis with cholestasis. The five children with severe hepatitis of unknown cause were all from Schneider Children's Medical Center in Israel in 2021.

The first type of "long-term new crown" hepatitis reported by the researchers occurred in two infants aged 3 and 5 months. They were previously healthy but rapidly developed acute liver failure requiring liver transplantation. Their livers showed massive necrosis with bile duct proliferation and lymphocytic infiltration.

Type II hepatitis with cholestasis occurred in 3 children (two 8 years old and one 13 years old). The investigators performed liver biopsies in 2 of the children, where lymphocyte hilum and parenchymal inflammation and bile duct proliferation were prominent. All three were treated with steroids, and liver enzymes improved and they were able to end treatment.

Notably, the investigators performed extensive etiological testing for infectious and metabolic etiologies in all five patients, which were negative, excluding other known causes.

Previously, the global clinical medical community has reported numerous cases of liver injury during acute infection of the new coronavirus; cases of bile duct inflammation after recovery from the infection of the new coronavirus have also been reported in adults. Among the 5 cases reported in Israel, the average onset time was 74.5 days (range 21-130 days) after the positive for the new coronavirus nucleic acid.

The imaging features of these 5 cases of "long-term COVID-19" hepatitis in Israel included increased periportal echogenicity, biliary dilatation, ductal, portal edema, and gallbladder wall thickening. Their histological features included ductal reaction, portal and sinus congestion, and portal and parenchymal lymphocytic infiltration. In terms of treatment, systemic corticosteroid therapy may be beneficial in similar patients.

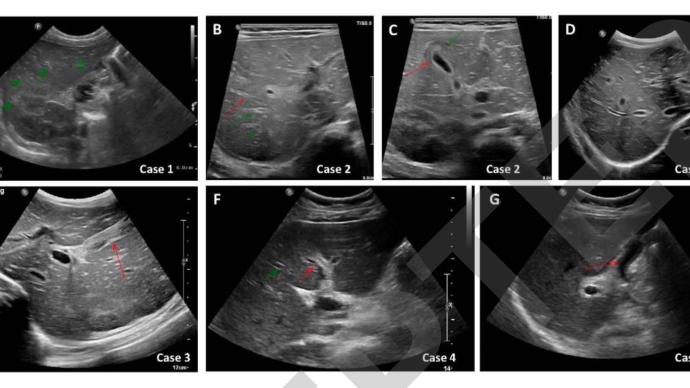

Table 1

figure 1

figure 2

image 3

acute liver failurePatient 1 is a 3-month-old infant who developed fever in February 2021 and was tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by nucleic acid.

He was born at 36 weeks gestation with a birth weight as low as 2300 grams, otherwise he is healthy and able to grow and develop normally. After being diagnosed with the new crown, he will not receive any treatment and will not need to be hospitalized.

But on the 21st day after the new crown diagnosis, he came to the hospital emergency room with 4 days of progressive jaundice. On arrival at the hospital, his temperature and vital signs were normal, and the physical examination was only significant for jaundice.

Laboratory test his AST (aspartate aminotransferase) up to 2078IU/L, ALT (alanine aminotransferase) up to 1440IU/L, GGT (glutamyl transferase) up to 63IU/L, ALP (alkaline phosphatase) Up to 2042IU/L, total bilirubin 18.5mg/dL, direct bilirubin 14.5mg/dL, albumin 4g/dL, ammonia 184mcg/dL, INR 5.5. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

Due to coagulopathy in patient 1, vitamin K was given, but the situation did not improve. He was taken to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of acute liver failure. Laboratory tests for infectious and metabolic causes were negative (Table 1). IgG antibody to SARS-CoV-2 was positive (3474AU/ml).

Genetically, a whole exome analysis was performed on patient 1 and his parents. In addition, regions associated with the acute liver failure phenotype, including NBAS and SCYL1 variants, were analyzed. Two compound heterozygous missense variants were detected in the gene MAN2B2 - c.112G>A;p.Asp38Asn and c.1211T>C;p.Leu404pro. Previous studies have shown that this variant of the gene is also present in patients without liver disease. Because these specific variants were not described in patients with liver failure in the literature or local databases in Israel, they were classified as variants of uncertain significance with low disease-causing potential.

Abdominal ultrasonography of patient 1 showed an increase in periportal echogenicity that was otherwise inconspicuous (Fig. 1A). As the synthetic function of the liver continued to deteriorate, he developed encephalopathy and required a liver transplant. Patient 1 underwent a living donor left liver transplant from his father on day 32 due to further deterioration of his condition. Histological examination of the liver of patient 1 showed pericentral and panlobular necrosis, prominent bile duct hyperplasia, and lymphocytic infiltration in the portal venous region and parenchyma. Staining was negative for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2A-C). The patient recovered well and continued with outpatient follow-up at the liver transplant clinic.

Patient 2 is a 5-month-old baby. In May 2021, he came to the emergency room with 2 days of jaundice, dark urine, and biliary soft stools. At that time, it was judged that no drug treatment was needed. Ten days before admission, he had worsening reflux and refusal to eat, and was started on Gaviscon (a stomach drug) for several days, followed by an anti-reflux formula, and his symptoms subsided.

Upon arrival at the hospital, Patient 2 had a fever to 38.0°C and normal vital signs. Physical examination was marked by jaundice and hepatomegaly. Laboratory tests are AST up to 2265IU/L, ALT up to 2219IU/L, GGT up to 124IU/L, ALP up to 1034IU/L, total bilirubin 7.7mg/dL, direct bilirubin 4.5mg/dL, albumin 4.3g /dL, ammonia 110 μg/dL. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

Patient 2's INR after vitamin K administration was 1.85. Patient 2 was taken to the intensive care unit for further examination. During admission, he developed secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) with cytopenias, high ferritin levels, hypofibrinogenemia, elevated IL-2 levels, and phagocytosis on liver histology. blood cells.

As part of the Primary Immunodeficiency Panel, we performed gene sequence analysis and deletion/duplication testing on 407 genes in Patient 2 due to HLH. Testing included NBAS variants, and results included a variant in NOD2, a gene known as risk for Crohn's disease, and variants of uncertain clinical significance in three gene factors, CIITA, DOCK8 and WDR1.

Patient 2 was listed as requiring liver transplantation because his INR continued to rise. On day 7 after admission, he had clinical deterioration with encephalopathy and subsequently received a living donor liver transplant from his mother (left segment).

Laboratory tests for infectious and metabolic causes of patient 2 revealed positive PCR for adenovirus in his whole blood (Table 1). IgG antibody to SARS-CoV-2 was positive (2629AU/ml). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed hepatomegaly, bile duct dilatation, periportal edema, and gallbladder wall thickening (Figures 1B and 1C).

Histological examination of the liver of patient 2 showed extensive panlobular necrosis, mainly pericentric necrosis, marked bile duct hyperplasia, and canalicular cholestasis. Hepatic sinusoids have extensive mononuclear cell infiltration and hemophagocytic signs. Staining was negative for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2D-F). Postoperatively, Child 2 was PCR positive for cytomegalovirus and adenovirus and received ganciclovir and cidofovir. Hepatic liver disease resolves spontaneously without specific treatment. Liver staining was negative for three viruses that may cause secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) (ie, CMV, adenovirus, and COVID-19).

Acute hepatitis with cholestasis

Patient 3 was an 8-year-old boy who was previously healthy. When his mother tested positive for the new coronavirus nucleic acid, he was also tested and found that he was also infected, but the symptoms were very mild, and he did not receive any treatment and was not admitted to the hospital.

On the 130th day after patient 3 was diagnosed with Covid-19, he was admitted to the emergency room with abdominal pain and vomiting for a week and jaundice for two days. He was afebrile, his vital signs were normal, and his physical examination revealed jaundice with hepatomegaly.

Laboratory testing on patient 3 showed that his AST was as high as 3598IU/L, ALT was as high as 3561IU/L, GGT was as high as 167IU/L, ALP was as high as 496IU/L, total bilirubin 8.1mg/dL, direct bilirubin 5.1mg /dL, albumin 4.2 g/dL and ammonia 50 mcg/dL. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

After vitamin K administration to patient 3, his INR was 1.5. Laboratory tests for infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic causes were negative (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed mild hepatomegaly, bile duct protrusion, and gallbladder wall edema (Figures 1D and 1E). On day 4 of admission, patient 3 underwent a liver biopsy. Histological examination was characterized by portal and sinusoidal congestion, bile duct hyperplasia, and marked lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltration in the portal space and lobules.

Patient 3 stained negative for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV, and SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 2G-I).

Patient 3 then began to receive methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg/day injection therapy. Its hepatocytes and cholestatic enzymes, INR were rapidly improved. He was subsequently switched to oral prednisolone and then gradually discontinued over 4 months (Figure 3). His liver enzymes fully returned to normal after 4 months and have remained normal ever since.

Patient 4 was an 8-year-old boy who had fever and cough in January 2021 and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid. He received no treatment and was not admitted to hospital.

His body mass index BMI was above 97% for his age, and he was known to have mildly elevated AST and ALT (79 IU/L and 47 IU/l, respectively), which was thought to be secondary to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease .

On the 94th day after the diagnosis of Covid-19 infection, patient 4 presented to the emergency room with three days of fever to 39°C, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea and jaundice. His temperature and vital signs were normal, and physical examination revealed hepatomegaly and jaundice.

Laboratory tests of patient 4 were AST up to 1551IU/L, ALT up to 2439IU/L, GGT up to 95IU/L, ALP up to 499IU/L, total bilirubin 10.3mg/dL, direct bilirubin 6.2mg/dL, white blood Protein 4.2g/dL, ammonia 71mcg/dL, INR1.2. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

The investigators performed laboratory tests for infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic causes in patient 4, which were negative (Table 1) and positive for IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (376 AU/ml). Abdominal ultrasound showed bile duct dilatation and gallbladder wall thickening (Figures 1F and 1G). A liver biopsy 13 days after admission revealed portal and sinus congestion, dilation and proliferation of bile duct margins, and prominent lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltration in the portal space and lobules.

The investigators stained patient 4 liver biopsy sections for adenovirus, EBV, CMV, HSV, and SARS-CoV-2, all of which were negative (Figure 2J-L). Two days after the liver biopsy, patient 4 was started on systemic steroids. ALT, AST, GGT, bilirubin, and ALP levels gradually decreased and returned to normal after 4 months, during which time the steroid medication was gradually discontinued (Figure 3). Two months after his visit, he was diagnosed with aplastic anemia. Targeted next-generation sequencing and analysis of the bone marrow failure gene panel was negative. He underwent a successful bone marrow transplant in September 2021 and is in good health.

Patient 5 was a previously healthy 13-year-old boy. In September 2021, he presented with 5 days of weakness, diarrhea and abdominal pain, and his temperature and vital signs were normal. Physical examination revealed jaundice. Laboratory tests on patient 5 showed AST up to 2901IU/L, ALT up to 9376IU/L, GGT up to 141IU/L, ALP up to 396IU/L, total bilirubin 12mg/dL, direct bilirubin 8.8mg/dL, Albumin 3.8g/dL, ammonia 62mcg/dL and INR 1.2. These data suggest that he developed severe liver damage.

Patient 5 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid and was hospitalized for observation, after which there was gradual clinical and laboratory improvement without medication, and his liver enzymes returned to normal 39 days after infection.

On day 53 of the COVID-19 diagnosis, patient 5 came to the emergency room with another 10 days of vomiting and abdominal pain. His fever and vital signs were normal. On physical examination, jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness were present. Laboratory tests were AST up to 8501IU/L, ALT up to 10560IU/L, GGT up to 66IU/L, ALP up to 445IU/L, total bilirubin 10.4mg/dL, direct bilirubin 6.6mg/dL, albumin 3.6g /dL and ammonia 214mcg/dL.

Laboratory tests for infectious, autoimmune, and metabolic causes were negative for patient 5 (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasonography was normal. On the day of admission, the patient was started on systemic steroids. ALT, AST, and ALP levels gradually decreased (Figure 3). Steroid therapy has now ended and his liver enzymes remain normal.

Histological features rule out adenoviral hepatitis

This Israeli study describes the clinical phenotypes of two liver manifestations associated with recent COVID-19 disease: acute liver failure and acute hepatitis with cholestasis. Previous studies have found that severe cholestasis occurs mainly in adults. In the Israeli study, two patients with acute liver failure were infants (3 and 5 months). The 3 patients with acute hepatitis with cholestasis were older (8-13 years).

The five patients were all asymptomatic or mildly ill with the new coronavirus. Their bile duct disease appeared months after the COVID-19 diagnosis. For four patients in Israel (another was transferred), the mean time from COVID-19 diagnosis to cholangiopathic diagnosis was 74.5 days (range 21-130). Patient 5 was found to have been infected with COVID-19 by serological testing, but the exact time of infection was unknown.

Similar to the description in adults, ultrasound studies of four patients in the Israeli study showed bile duct or gallbladder involvement. Specifically, hepatomegaly, bile duct dilatation, periportal edema, or edema and thickening of the gallbladder wall were found to be significant. In adults, ultrasonographic findings are mainly applicable to focal strictures of the intrahepatic bile ducts with intraluminal sludge and casts, consistent with the radiographic features of SSC.

Liver histology from the Israeli study showed some similarities between patients. Biopsy showed statistically significant bile duct hyperplasia, portal and sinus congestion, portal lymphocyte infiltration, eosinophilic infiltration, and hepatic parenchyma inflammatory infiltration. A previous systematic review of histopathological findings on liver biopsies in adults with COVID-19 showed that the most common findings were centrilobular hyperemia and steatosis, which are associated with pre-existing obesity and diabetes. Other findings described in adults include hepatocyte necrosis, mild to moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the periportal area, cholestasis with biliary embolism, ductal reaction, and cholangiocyte nuclear polymorphism.

In contrast to the adult cohort, in the pediatric cohort of this study from Israel, steatosis was absent, the researchers noted. This may imply that the steatosis observed in the adult cohort is related to other comorbidities than to COVID-19.

More recently, severe acute hepatitis has been reported in increasing numbers of children in the UK, EU, US, Israel and Japan. In England and Scotland, 68% and 50% of cases respectively tested positive for adenovirus, mainly in blood. The etiology of the cases is unclear, as adenoviruses usually cause severe hepatitis only in immunocompromised hosts.

Nevertheless, the increased incidence of adenovirus in the described cases prompted the Israeli study to further confirm whether an adenovirus infection might be involved, the researchers said. Previous studies have shown that histological features of adenoviral hepatitis include extensive hepatocyte necrosis, mild inflammation, intranuclear inclusions, and positive immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens in infected hepatocytes. Specimens described by the European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention included six explanted livers and eight biopsies from cases in the UK and Scotland. Adenovirus immunohistochemistry has been reported in 9 out of 14 samples to date, showing immunoreactivity in the hepatic sinusoid lumen but not in hepatocytes. 1 routine liver tissue adenovirus polymerase chain reaction, the result was negative.

They cite another previous study from other laboratories that described liver biopsies from six pediatric patients showing varying degrees of hepatitis, but no viral inclusions were observed, no immunohistochemical evidence for adenovirus, and no pass Electron microscopy to identify virus particles.

Notably, the Israeli study also performed adenovirus immunohistochemical staining in all patients who underwent liver biopsy or liver explantation. Adenovirus staining was negative, and histological features were not suggestive of adenovirus hepatitis. Three patients had adenovirus PCR from whole blood, and one patient was positive. However, since liver histology did not suggest adenovirus infection, the Israeli study did not consider it to be the culprit for unexplained childhood hepatitis.

Related Posts

0 Comments

Write A Comments